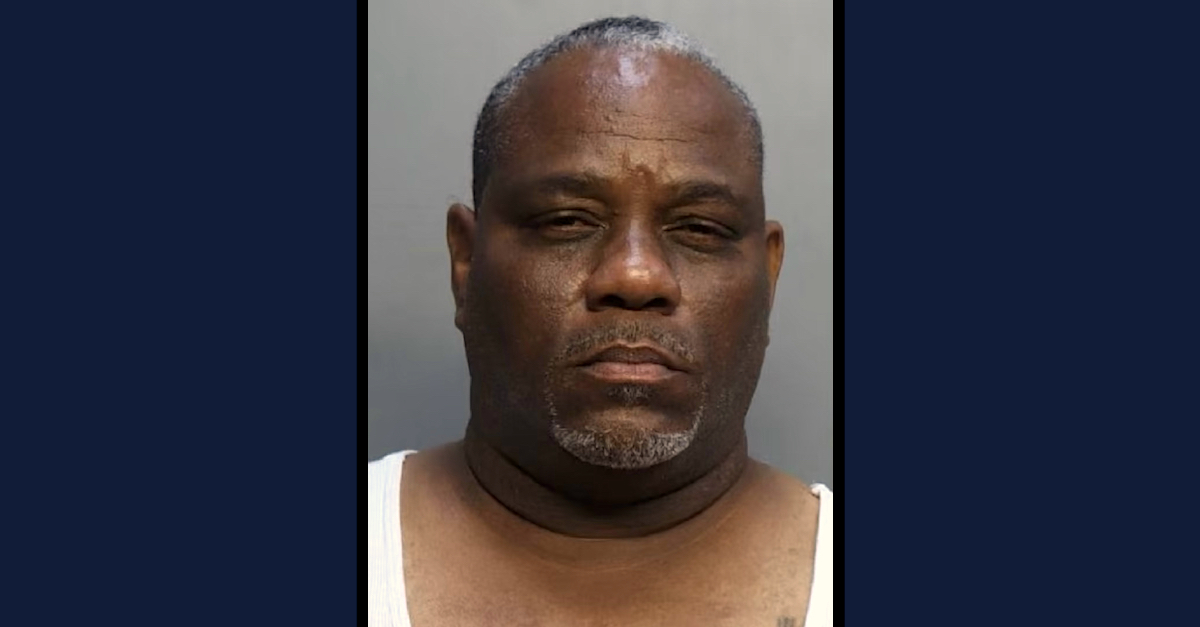

Robert Lee Wood.

A Florida judge has used “very narrow” technical grounds to dismiss a case against a man accused of violating the Sunshine State’s election laws.

Robert Lee Wood, 56, of Miami was one of nearly two dozen defendants rounded up by an election police unit assembled at the behest of Gov. Ron DeSantis (R). Miami-Dade County court records say Wood was charged with two election law felonies: registering as an unqualified voter and falsely voting.

According to an order obtained by Law&Crime, Miami-Dade Circuit Judge Milton Hirsch dismissed the case after Wood’s attorney argued that the prosecutor’s office who filed the twin charges had no jurisdiction to do so.

Wood was prosecuted by the Office of Statewide Prosecution. According to its website, the Office of Statewide Prosecution is legally restricted to efforts against “crimes that impact two or more judicial circuits in the State of Florida.”

“Working regularly with state and federal counterparts, the office focuses on complex, often large scale, organized criminal activity,” the website continues. “The Office of Statewide Prosecution is authorized to act throughout Florida and works closely with law enforcement and State Attorneys to coordinate the prosecutions of multi-circuit violations of State law.”

The statewide prosecutor is appointed by the AG, the site adds.

Examples of typical cases handled by the office, according to its own press releases, are an “eight county crime spree,” a retail theft ring that spanned 14 counties, and a pool contractor who committed frauds in at least six counties.

Judge Hirsch said the office’s limited jurisdiction necessitated throwing out Wood’s case, but he was careful in so doing:

The present prosecution is brought, not by the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office, but by the Office of the Statewide Prosecutor (“OSP”). OSP is empowered to bring criminal prosecutions in Florida when one of two conditions is met: either the demised crime must have occurred “in two or more judicial circuits as part of a related transaction,” or the crime must be “connected with an organized criminal conspiracy affecting two or more judicial circuits.” Fla. Stat. § 16.56(1)(a). Claiming that neither condition is met here, Robert Lee Wood moves to dismiss for lack of statutory authority to prosecute on OSP’s part. Thus the issue before me is not whether Mr. Wood committed the crimes charged, nor even whether he is amenable to prosecution for the crimes charged. The very narrow issue raised by the present motion is whether Mr. Wood is amenable to prosecution by OSP for the crimes charged.

According to Hirsch’s opinion, both sides stipulated for purposes of a jurisdictional argument that Wood filled out a voter application form in Miami-Dade County on Sept. 30, 2020. The county supervisor of elections forwarded the form to the Florida Secretary of State. About a month later, the Secretary of State verified the application and “issued a voter ID card to Mr. Wood.” Wood then voted in the November 2020 general election. His ballot was eventually tabulated in Tallahassee because that is where the state sends such ballots.

The OSP attempted to argue that because Wood’s ballot was sent from Miami to Tallahassee, the multi-district nature of its jurisdiction had been triggered. But Wood never physically entered the Tallahassee’s judicial circuit and did not himself mail or transfer anything to that circuit.

The state also admitted that no “criminal conspiracy” was afoot.

Hirsch rubbished those prosecutorial assertions.

“Voter application forms, and completed ballots, are, as a matter of course, shipped off to Tallahassee from all corners of Florida for tabulation,” the judge noted. “Yes, his voter application and his ballot were transported to another Florida jurisdiction. But they were not transported by him, nor by any putatively criminal co-perpetrator. They were not transported by someone whose role in Mr. Wood’s crime was to transport them. They were not transported at Mr. Wood’s behest or bidding.”

“I am willing to construe the prosecutorial authority of the statewide prosecutor to the very limits of the statutory language creating that authority — to those limits, and not a jot further,” the judge wrote while strictly construing the text of the statute in question.

The judge rubbished the OSP’s broad assertions of its own power and authority starting with a footnote.

“Ironically — and unmentioned by OSP — the only exception would be for voter fraud perpetrated in the state capitol,” Hirsch explained. “A Leon County domiciliary can, on OSP’s interpretation of the statute, commit voter fraud to his heart’s content without fear of prosecution by OSP. Such a fraudfeasor’s ballots would be cast, and tabulated, within a single circuit.”

That is because a Leon County ballot would be transmitted to state agents only within Leon County, which surrounds Tallahassee.

When followed to its logical extreme, the OSP’s argument was that the legislature intended to allow the OSP “to prosecute all election-related crimes in all Florida counties except Leon County,” the judge wrote. He then said the OSP did not even “attempt to reconcile that incongruity” and thus jettisoned the entire jurisdictional argument as hogwash.

“One wonders how far OSP is willing to take its argument,” the judge openly mused before spinning a few more hypotheticals by employing the OSP’s arguments. The judge said those possible outcomes that were so ridiculous that they “hardly invite[d] rebuttal.”

The judge then noted several cases involving “the same criminals or their confederates . . . in two Florida counties” — precisely the type pointed out by OSP press releases as the heart of OSP jurisdiction.

“Here, all the criminal misconduct, if there was any, was performed by one man in that county,” the judge indicated while distinguishing Wood’s case.

A few more rhetorical flourishes served as a coup de grace to the state’s arguments:

It is an old truth that all politics is local. OSP seeks to stand that old truth on its head. It seeks, by its own frank admission, authority to prosecute “all criminal cases dealing with voter registration and elections,” wherever in Florida they may be, however local they may be. [Citation omitted.] That plenary power — the power to invigilate all Florida elections, whether federal, state, or municipal — is not consigned to OSP by § 16.56.

“His arms spread wider than a dragon’s wings,” says Shakespeare’s Duke of Gloucester about Henry V. [Citation omitted.] How much wider even than that does OSP seek to extend its reach? In the case at bar the answer is simple: wider than the enabling statute contemplates, and therefore too wide.

The Tampa Bay Times reported that “Wood was convicted of second-degree murder in 1991, making him ineligible to vote.”

DeSantis argued last winter that Florida needed a special police force to handle election issues. DeSantis then announced that assembled force had netted a bevy of arrests in August.

“They did not go through any process, they did not get their rights restored, and yet they went ahead and voted anyways,” DeSantis said of the defendants while announcing the arrests during what the PBS NewsHour described as “a campaign-style event in Fort Lauderdale before cheering supporters.”

“That is against the law,” DeSantis said as to the arrested individuals, “and now they’re gonna pay the price for it.”

The NewsHour then provided this context:

Voter fraud is rare, typically occurs in isolated instances and is generally detected. An Associated Press investigation of the 2020 presidential election found fewer than 475 potential cases of voter fraud out of 25.5 million ballots cast in the six states where Trump and his allies disputed his loss to Democratic President Joe Biden. DeSantis has previously praised Florida for carrying out a smooth election in 2020.

None of the court documents filed in connection with Wood’s case are immediately available on a Miami-Dade circuit court website. That is odd, because most Florida court records are easily accessible online.

The Tampa Bay Times noted that prosecutors could appeal the dismissal.

The newspaper also said that election law cases are “difficult” to prosecute when they are brought by the proper authorities. That’s because the law requires the state to prove that a voter “willfully” committed a crime.

For instance, Lake County prosecutor Jonathan Olson refused to press cases against six sex offenders who voted in 2020. Olson said those individuals “been encouraged to vote by various mailings and misinformation” and “were given voter registration cards which would lead one to believe they could legally vote in the election,” the newspaper reported.

Body camera video of some of the arrests conducted by Florida authorities were recently released.

Wood’s case is number 13-2022-CF-015009-0001-XX in Miami-Dade county.

The dismissal order is available here.

[Image via mugshot.]