Alex Murdaugh (left) and his son Paul Murdaugh (right) appear in jail mugshots.

A federal judge last week ruled that a Pennsylvania-based insurance company is not on the hook for any potential liabilities generated by suspended South Carolina attorney Richard Alexander “Alex” Murdaugh or his son Richard Alexander “Buster” Murdaugh, Jr. in connection with the death of a teen in a 2019 boating accident.

“He expected one thing,” the judge said while referring to Murdaugh’s purchase of insurance. “He received something else.” The judge said that’s a problem for the Murdaughs — and not a problem the courts can fix.

This image taken by a South Carolina coroner shows a boat owned by Alex Murdaugh and allegedly operated by Paul Murdaugh after it crashed into a bridge pier on Feb. 23, 2019. (Image obtained from the South Carolina Attorney General’s Office pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request by Law&Crime.)

The insurance case is tightly connected to an underlying lawsuit concerning the death of Mallory Beach, 19. According to multiple civil lawsuits, Beach died when Alex’s son (and Buster’s brother) Paul Murdaugh bought alcohol using Buster’s driver license at a convenience store. Paul allegedly became drunk after the purchase and operated a boat owned by his father Alex. Paul allegedly crashed into a bridge pier; Beach, one of his passengers, died as a result of the Feb. 23, 2019 collision. Civil litigation against the Murdaughs ensued.

Paul Murdaugh was captured by a security camera leaving a Parker’s convenience store carrying several cases of alcohol prior to the boat crash which killed Mallory Beach. (Image obtained from the South Carolina Attorney General’s Office pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request by Law&Crime.)

Immediately after the civil litigation was filed, the Philadelphia Indemnity Insurance Company itself filed a declaratory judgment action in U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina. Declaratory judgment actions are legal maneuvers which ask judges to decide controversies that are necessary to settle before a bigger-picture dispute on the merits occurs. In this case, the bigger-picture controversy is whether and to what degree the various Murdaughs are liable for the injuries suffered by Beach. The smaller yet financially critical question is whether Murdaugh’s insurance policy with Philadelphia Indemnity Insurance will pay for any of those damages and for any associated defense for the Murdaugh family. The named defendants in the insurance company’s action were Alex Murdaugh, Buster Murdaugh, and Renee S. Beach, Mallory Beach’s mother.

At issue were a $3 million commercial liability insurance policy and a $5 million umbrella protection policy Murdaugh tried unsuccessfully to argue covered any potential damages in the underlying Beach lawsuit.

As federal judge Sherri A. Lydon explained in a Sept. 21 decision, the insurance company raised five arguments as to why it should not pay for any damages or pay to defend the Murdaughs:

(1) the Murdaugh Defendants are not insureds under the policies; (2) the policies only provide coverage for “bodily injury” that arises out of private hunting operations; (3) the Underlying Lawsuit does not allege an “occurrence;” (4) the watercraft exclusion applies to exclude coverage; and (5) because there is no coverage, it has no duty to defend or indemnify.

The insurance policy explicitly applied to an alleged business which provided the services of “Guides & Outfitters.” Therefore, Judge Lydon agreed with the insurance company that the underlying allegations of drunken boating didn’t qualify as an insured activity. Nor did Buster Murdaugh meet the definitions of being an insured party in the first place. He wasn’t working for his father (who took out the policy) as a “volunteer worker” or an “employee” of a guiding or outfitting business as the policy required.

This image taken by a South Carolina coroner shows what appear to be blood stains inside a boat owned by Alex Murdaugh and allegedly operated by Paul Murdaugh after it crashed into a bridge pier on Feb. 23, 2019. (Image obtained from the South Carolina Attorney General’s Office pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request by Law&Crime.)

The Murdaughs countered that the insurance company’s legal position rendered its policy merely “illusory.” That is, the Murdaughs alleged they were given the illusion that they were covered when, indeed, they were not. Judge Lydon explained the underlying law:

The doctrine is intended to protect insureds where the terms of an insurance policy exclude from coverage the very risk contemplated by the parties, rendering a policy provision virtually meaningless. It applies where the language of the policy negates virtually all coverage for the insured, and the insurance contract, read literally, is a delusion to the insured. Stated differently, the doctrine applies when exclusions in effect allow the insurer to receive premiums when realistically it is not incurring any risk of liability.

The judge then ruled against the Murdaughs: “South Carolina’s illusory coverage doctrine simply does not extend as far as the Murdaugh Defendants suggest.”

Again, from Judge Lydon’s opinion:

In his affidavit, Murdaugh submits that while he does engage in Private Hunting Operations, he does not engage in those operations as a business. Accordingly, Murdaugh argues that if he is required to be engaged in the conduct of a business of which you are the sole owner to obtain coverage, he would never be afforded coverage in any circumstance. This argument does not establish (or even suggest) that the policy is illusory, however.

[ . . . ]

[T]he Murdaugh Defendants do not point to a section of the policy providing that its intent is to provide coverage for a boating crash, followed by an exclusion taking away that same intended coverage. Murdaugh also does not present any evidence to suggest that the policy provides no coverage in the event an individual is injured as a result of the admitted private hunting operations that take place on the property. The court has no reason to believe that the policies would not provide coverage in the event all other policy requirements are met—bodily injury is the result of an occurrence, during the policy period, within the coverage territory, etc. Accordingly, Murdaugh’s affidavit establishes—at best—a mistake on his part. He thought he was purchasing one type of coverage but ended up with some another type of coverage (but coverage nonetheless). He expected one thing. He received something else. The question then is whether this scenario renders the policy an illusory one? From this court’s perspective, it does not.

In other words, Murdaugh screwed up when he bought the insurance policy in the first place. Murdaugh attempted to argue that he purchased the insurance for exactly the sort of catastrophe that befell his family — namely, the boating crash that left Mallory Beach dead.

“The fact that Murdaugh wants the policies to cover the boating crash, and they may not, does not render the policies illusory,” the judge replied. “Anyone reading the policy would know that the coverage provided is limited to the business stated. The limitation is not hidden. It is repeated in several places. And the language used is unambiguous in all respects. Thus, there is no evidence in the record to support even an inference that the two policies are illusory.”

Paul, Maggie, Alex, and Buster Murdaugh appear in an image obtained by NBC’s “Today.”

The Murdaugh boat was separately insured by Progressive Northern Insurance Company for a substantially lesser sum of $500,000. That company was not a party to the Philadelphia Indemnity Insurance lawsuit, Judge Lydon noted. She further ruled that the separate Progressive Northern Insurance policy did not trigger an umbrella policy Murdaugh purchased with Philadelphia Indemnity. That portion of the judge’s opinion contained this pointed paragraph which functionally upbraids Murdaugh — an attorney — for arguing for an interpretation of coverage that his own insurance policy did not support:

An opening note: Analyzing and interpreting an insurance contract requires more page flipping and cross-referencing than any other task this court faces. The Murdaugh Defendants’ arguments with respect to the Umbrella Policy’s definition of “insured” epitomize that reality. While the court is forced to walk through each relevant and applicable provision in painstaking detail, deconstructing the language at each step and mapping out the flaws or missteps in the Murdaugh Defendants’ analysis, the reality is that the issue simply is not that complicated. It can be summed up in two sentences. Sentence 1: A plain reading of the Umbrella Policy makes it abundantly clear that it goes hand-in-hand with the CGL Policy. Sentence 2: If the Murdaugh Defendants’ alleged actions in the Underlying Lawsuit do not bring them within the definition of “insured” in the CGL [commercial] Policy, they cannot qualify as “insureds” under Part (f) of Section II of the Umbrella Policy.

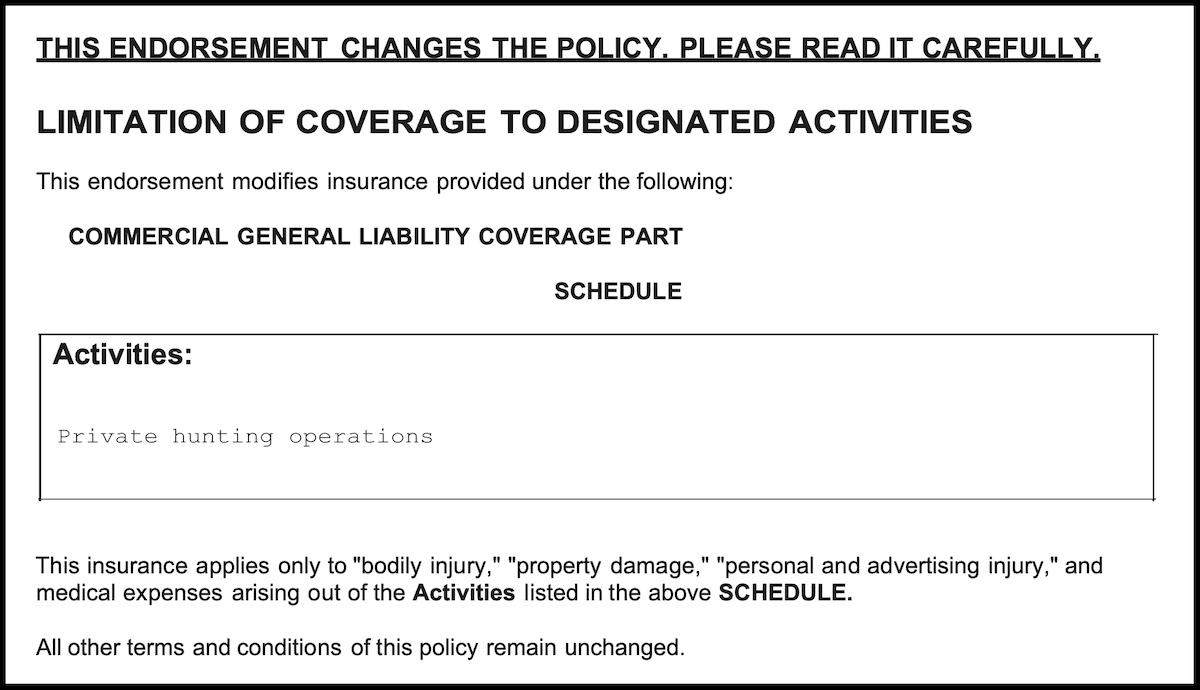

Further, Judge Lydon said that policy endorsement limited the coverage to which Murdaugh was entitled because it only provided insurance for “bodily injury, property damage, personal and advertising injury, and medical expenses” arising from “[p]rivate hunting operations.” The judge deftly provided a screenshot of the endorsement while referencing it in her opinion:

As to the endorsement, the judge pointed out the obvious: “there are simply no allegations of bodily injury arising out of private hunting operations” in the underlying civil litigation regarding the death of Mallory Beach.

Here’s how the judge wrapped up her opinion:

Plaintiff is entitled to judgment as a matter of law on its request for a declaration that there is no coverage available to the Murdaugh Defendants based on the allegations in the Underlying Lawsuit. Plaintiff has no duty to defend the Murdaugh Defendants in that action. Having concluded that Plaintiff is entitled to judgment as a matter of law with respect to the Murdaugh Defendants failing to qualify as “insureds” under the two policies and the Underlying Lawsuit failing to allege a bodily injury arising out of private hunting operations, the court declines to reach the parties’ arguments on “occurrence” and the two policy exclusions.

Paul Murdaugh and his mother Maggie Murdaugh were murdered this past summer on the family’s hunting lodge, “Moselle.” The killer remains unknown. Alex Murdaugh is facing criminal prosecution for allegedly hiring a former client to shoot and kill him so that his surviving son Buster could reap the advantages of a $10 million life insurance policy.

Investigators found copious quantities of beer and alcohol — in both open and unopened containers — after the crash of a boat owned by Alex Murdaugh. (Image obtained from the South Carolina Attorney General’s Office pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request by Law&Crime.)

Mallory Beach’s mother fought unsuccessfully to have the insurance company’s declaratory judgement case dismissed:

Through its agents, Plaintiff underwrote and issued the insurance policies at issue knowing Defendants Murdaugh’s potential risks and the necessary protections they were seeking through insurance coverage. Further, they assured Murdaugh that his interests would be protected and that there was coverage under the policy. These assurances were made despite the fact that the underwriters, producers and Philadelphia knew that Murdaugh had no hunting business nor any hotel.

Defendants Murdaugh and Plaintiff intended the policies to cover, among other things, the type of damage alleged in the underlying complaint filed in Hampton County Court of Common Pleas. Further, Murdaugh reasonably expected he would be covered from matters such as these.

If the polices are deemed not to cover the damages claimed in the underlying complaint, which Defendant Beach denies, then Defendants Murdaugh are entitled to reformation of the policies to cover such damage.

Those arguments appear to have gone nowhere; they were barely mentioned in cursory fashion in Judge Lydon’s opinion.

Progressive is defending the Murdaughs in Beach’s lawsuit, court documents indicate.

Investigators found copious quantities of beer and alcohol — in both open and unopened containers — after the crash of a boat owned by Alex Murdaugh. (Image obtained from the South Carolina Attorney General’s Office pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request by Law&Crime.)

Investigators found copious quantities of beer and alcohol — in both open and unopened containers — after the crash of a boat owned by Alex Murdaugh. (Image obtained from the South Carolina Attorney General’s Office pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request by Law&Crime.)

A boat owned by Alex Murdaugh and allegedly operated by Paul Murdaugh was covered in police tape after it crashed into a bridge pier on Feb. 23, 2019. (Image obtained from the South Carolina Attorney General’s Office pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request by Law&Crime.)

Read the judge’s full opinion below:

Editor’s note: citations and internal punctuation marks have been omitted from quotes in this piece to make it easier to read.