A federal judge hammered the judge-made doctrine of qualified immunity in a ruling granting qualified immunity to a police officer on Tuesday.

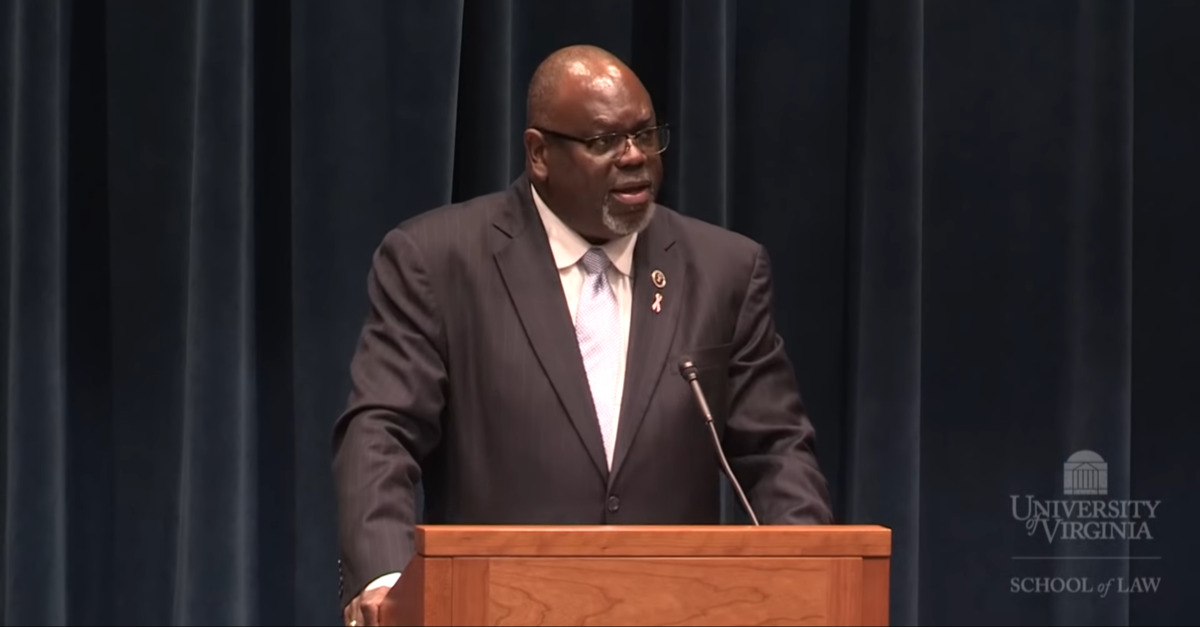

In a 72-page opinion and order, U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves, an outspoken critic of American culture/racism past and present, ultimately ruled in favor of a white police officer, Nick McClendon, who was sued for racially-profiling and terrorizing a Black working man, Clarence Jamison, on the side of the highway in 2013.

In the process, however, the Mississippi jurist laid down the gauntlet and called for the doctrine to be cast into the dustbin of American history.

Reeves said the Supreme Court should “eliminate” qualified immunity just as it swept away “separate but equal.”

“Over-turning qualified immunity will undoubtedly impact our society,” Reeves writes. “Yet, the status quo is extraordinary and unsustainable. Just as the Supreme Court swept away the mistaken doctrine of ‘separate but equal,’ so too should it eliminate the doctrine of qualified immunity.”

The opinion begins with a lengthy–though non-exhaustive–and poetic recitation of the names of Black people killed in recent years by police officers who largely went unpunished. Using the formal device of footnotes to catalogue those police killings, the judge notes what Jamison did not do before McClendon changed his life forever.

From the “must-read” opinion’s introduction:

Clarence Jamison wasn’t jaywalking. He wasn’t outside playing with a toy gun. He didn’t look like a “suspicious person.” He wasn’t suspected of “selling loose, untaxed cigarettes.” He wasn’t suspected of passing a counterfeit $20 bill. He didn’t look like anyone suspected of a crime. He wasn’t mentally ill and in need of help. He wasn’t assisting an autistic patient who had wandered away from a group home. He wasn’t walking home from an after-school job. He wasn’t walking back from a restaurant. He wasn’t hanging out on a college campus. He wasn’t standing outside of his apartment. He wasn’t inside his apartment eating ice cream. He wasn’t sleeping in his bed. He wasn’t sleeping in his car. He didn’t make an “improper lane change.” He didn’t have a broken tail light. He wasn’t driving over the speed limit. He wasn’t driving under the speed limit.

“No, Clarence Jamison was a Black man driving a Mercedes convertible,” Reeves goes on to note–his only crime before he “was pulled over and subjected to one hundred and ten minutes of an armed police officer badgering him, pressuring him, lying to him, and then searching his car top-to-bottom for drugs.”

The white officer was apparently unmoved by several background checks and a search of the car’s records that vindicated Jamison’s ownership of an expensive car. And even after the initial search–based on what the opinion says was “a lie” about a cocaine shipment being reported to his department–the cop kept going.

“Unsatisfied, the officer then brought out a canine to sniff the car,” Reeves recounts. “The dog found nothing. So nearly two hours after it started, the officer left Jamison by the side of the road to put his car back together. Thankfully, Jamison left the stop with his life. Too many others have not.”

The judge went on to explain the controversial, judicially-crafted exception to the nation’s premier Civil Rights enforcement mechanism–42 U.S.C. §1983–which allows an injured person to sue a state government agent for “the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution of the United States.”

“The Constitution says everyone is entitled to equal protection of the law – even at the hands of law enforcement,” the opinion explains. “Over the decades, however, judges have invented a legal doctrine to protect law enforcement officers from having to face any consequences for wrongdoing. The doctrine is called ‘qualified immunity.’ In real life it operates like absolute immunity.”

The doctrine of qualified immunity for police officers was created by activist conservatives on the typically liberal Earl Warren Court via the 1967 decision of Pierson v. Ray. In that case, an 8-1 majority of the justices read an immunity defense into the Civil Rights Act of 1871–which is also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871.

“Tragically, thousands have died at the hands of law enforcement over the years, and the death toll continues to rise,” the decision goes on. “Countless more have suffered from other forms of abuse and misconduct by police. Qualified immunity has served as a shield for these officers, protecting them from accountability.”

Reeves explains the doctrine’s evolution [emphasis in original]:

Once, qualified immunity protected officers who acted in good faith. The doctrine now protects all officers, no matter how egregious their conduct, if the law they broke was not “clearly established.”

This “clearly established” requirement is not in the Constitution or a federal statute. The Supreme Court came up with it in 1982. In 1986, the Court then “evolved” the qualified immunity defense to spread its blessings “to all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law.” It further ratcheted up the standard in 2011, when it added the words “beyond debate.” In other words, “for the law to be clearly established, it must have been ‘beyond debate’ that [the officer] broke the law.”

Still, despite all his rage at the unjust series of events before him, Reeves said that precedent forced his hand to deliver a win for McClendon on qualified immunity grounds.

The decision notes:

This Court is required to apply the law as stated by the Supreme Court. Under that law, the officer who transformed a short traffic stop into an almost two-hour, life-altering ordeal is entitled to qualified immunity. The officer’s motion seeking as much is therefore granted.

But let us not be fooled by legal jargon. Immunity is not exoneration. And the harm in this case to one man sheds light on the harm done to the nation by this manufactured doctrine.

The ruling also spends several pages detailing the history of state-sanctioned white violence against African-Americans following the Civil War; the genesis of §1983–as well as several efforts by the nation’s high court to claw back redress for people abused by government agents.

Reeves witheringly assessed the upshot of qualified immunity doctrine:

A review of our qualified immunity precedent makes clear that the [Supreme] Court has dispensed with any pretense of balancing competing values. Our courts have shielded a police officer who shot a child while the officer was attempting to shoot the family dog; prison guards who forced a prisoner to sleep in cells “covered in feces” for days; police officers who stole over $225,000 worth of property; a deputy who body- slammed a woman after she simply “ignored [the deputy’s] command and walked away”; an officer who seriously burned a woman after detonating a “flashbang” device in the bedroom where she was sleeping; an officer who deployed a dog against a suspect who “claim[ed] that he surrendered by raising his hands in the air”; and an officer who shot an unarmed woman eight times after she threw a knife and glass at a police dog that was attacking her brother.

The judge’s atypically-styled opinion on a matter of recent national importance and its atypical expression of ethical outrage immediately prompted some attorneys to float Reeves’ name as a potential Supreme Court pick in a theoretical Joe Biden administration.

Others suggested that a Democratic administration might be inclined to nominate someone younger than Reeves, who is 56.

Read the full opinion and order below:

Jamison v McClendon by Law&Crime on Scribd

[image via screengrab/University of Virginia School of Law]