The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit on Wednesday ruled that the U.S. government violated the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) by collecting the bulk phone records of millions of Americans.

Under the relevant section of the FISA law, the government is authorized to apply to the secret FISA Court for an “order requiring the production of any tangible things (including … records …) for an investigation to obtain foreign intelligence information not concerning a United States person or to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities” but only if they include “a statement of facts showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the tangible things sought are relevant to an authorized investigation (other than a threat assessment).”

The metadata collection program, however, was not actually relevant to any particular authorized investigation–it was a broad-based effort to spy on people by collecting vast swathes of data and then using the data to mount and/or sustain prosecutions after the fact.

The government offered a circular argument that the term “relevant” applies to every piece of metadata collected by the program because the spying apparatus was based on the mass collection of such data.

Judge Marsha S. Berzon shut down that line of thought:

Defendants respond that Congress intended for the relevance requirement to be a limiting principle. They argue that the government’s interpretation of the word “relevant” is essentially limitless and so contravenes the statute. Defendants rely principally on [a previous case implicating the bulk collection program], which held that the text of section 1861 “cannot bear the weight the government asks us to assign to it, and . . . does not authorize the telephone metadata program.” We agree.

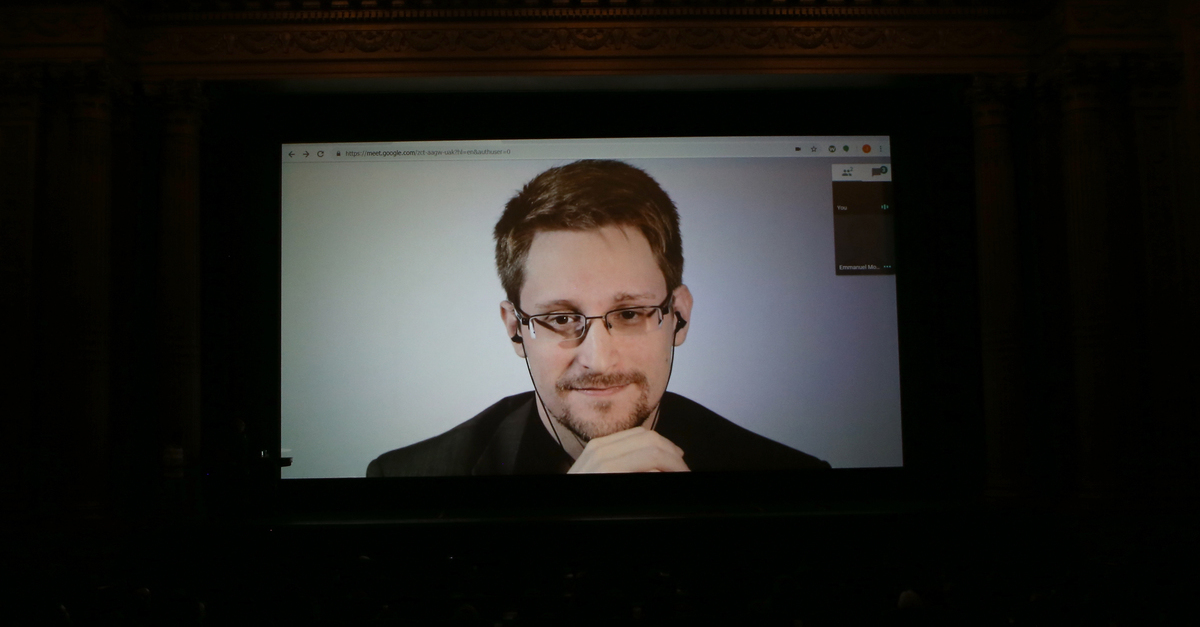

The existence of the program, of course, came under harsh national focus and inspired outrage across the country when whistleblower Edward Snowden worked with several news outlets to leak classified information about the NSA’s bulk collection program. The court repeatedly references Snowden’s efforts in this regard.

“[I]n June 2013, former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden made public the existence of NSA data collection programs,” the decision notes. “One such program, conducted under FISA Subchapter IV, involved the bulk collection of phone records, known as telephony metadata, from telecommunications providers. Other programs, conducted under the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, involved the collection of electronic communications, such as email messages and video chats, including those of people in the United States.”

After Snowden’s identity was revealed, the administration of Barack Obama responded by revoking Snowden’s U.S. Passport, forcing him to relocate to Russia.

Snowden took a victory lap over the court’s Wednesday ruling.

“Seven years ago, as the news declared I was being charged as a criminal for speaking the truth, I never imagined that I would live to see our courts condemn the NSA’s activities as unlawful and in the same ruling credit me for exposing them,” he wrote. “And yet that day has arrived.”

Another similarly situated whistleblower, Thomas Drake, who was prosecuted by the Obama administration for leaking information about alleged NSA crimes, fraud, waste and abuse, also responded to the ruling.

“Paging [Snowden]— 9th Circuit declares NSA program unlawful as intel officials misled, lied & covered up NSA’s bulk call record collection (err, mass surveillance) as National Security State] secret,” Drake wrote. “Some of us [were] charged like spies [with] Crimes against the State for exposing this spying post 9/11.”

In an additional and fairly standard analysis of Fourth Amendment issues, the court also said the bulk hoovering operation by the National Security Agency (NSA) was likely in violation of the Fourth Amendment rights of the plaintiffs in the case stylized as U.S. v. Moalin–but the court declined to rule definitively on the constitutional issue because the likely constitutional violation here “did not taint the evidence introduced by the government at trial.”

“The government did not notify defendants that it had collected Moalin’s phone records as part of the metadata program,” the ruling notes–before returning again to Snowden’s role in the case. “Defendants learned that after trial—from the public statements that government officials made in the wake of the Snowden disclosures.”

But the government’s use of that illegal program wasn’t fatal to the government’s prosecution here.

“Contrary to defendants’ assumption, the government maintains that Moalin’s metadata ‘did not and was not necessary to support the requisite probable cause showing’ for the Subchapter I application in this case,” Berzon concludes. “Our review of the classified record confirms this representation.”

It’s important to understand that the Fourth Amendment functions like a shield that protects criminal defendants against unreasonable searches and seizures. But the scope of that shield has been consistently limited and chipped away by Supreme Court rulings over the past several decades. One workaround for the government is claiming—and convincing a court—that the initial unconstitutional behavior didn’t have much impact on the prosecution’s outcome.

In Moalin, the court found that the government’s telephonic metadata collection, while definitely unlawful and probably unconstitutional, simply didn’t influence the overall proceedings enough and therefore there was no remedy under the Fourth Amendment available to the defendants. And, because there was no Fourth Amendment remedy, the court effectively punted on the constitutional issue–while strongly suggesting the U.S. Constitution was, in fact, violated by the NSA’s bulk collection scheme:

Like the cell phone location information in [another Fourth Amendment case], telephony metadata, “as applied to individual telephone subscribers, particularly with relation to mobile phone services and when collected on an ongoing basis with respect to all of an individual’s calls . . . permit something akin to . . . 24-hour surveillance . . . .” This long-term surveillance, made possible by new technology, upends conventional expectations of privacy. Historically, “surveillance for any extended period of time was difficult and costly and therefore rarely undertaken.” Society may not have recognized as reasonable [the defendant in another Fourth Amendment case’s] expectation of privacy in a few days’ worth of dialed numbers but is much more likely to perceive as private several years’ worth of telephony metadata collected on an ongoing, daily basis—as demonstrated by the public outcry following the revelation of the metadata collection program.

President Donald Trump recently suggested he might consider pardoning Snowden. He said he would “take a look at that very strongly.” Attorney General Bill Barr and various op-ed pages have expressed “vehement” opposition to such clemency.

[image via Phillip Faraone/Getty Images for WIRED25]