The long-awaited report from Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz was released as expected on Monday. Also as expected, the 400-page report said that the origins of the FBI’s Russia investigation ultimately had a proper and legal factual basis — despite numerous procedural shortcomings at the bureau, and despite a criminal referral related to low-level ex-FBI lawyer Kevin Clinesmith’s alleged alteration of an email used in an application to surveil former Trump adviser Carter Page.

The bottom line: it’s a mixed bag and there was some strong scolding of the FBI’s failures–“We are deeply concerned that so many basic and fundamental errors were made by three separate, hand-picked investigative teams…”–but the Horowitz report doesn’t support conspiracy theories President Donald Trump and his supporters have pushed about a politically-motivated coup at the FBI to topple this presidency.

Nonetheless, both Attorney General William Barr and John Durham, the U.S. Attorney that Barr tasked to investigate the origins of the Mueller Probe, released statements disagreeing with some of Horowitz’s findings.

“The Inspector General’s report now makes clear that the FBI launched an intrusive investigation of a U.S. presidential campaign on the thinnest of suspicions that, in my view, were insufficient to justify the steps taken,” Barr said. “It is also clear that, from its inception, the evidence produced by the investigation was consistently exculpatory.”

Then came the Durham statement.

“I have the utmost respect for the mission of the Office of Inspector General and the comprehensive work that went into the report prepared by Mr. Horowitz and his staff. However, our investigation is not limited to developing information from within component parts of the Justice Department,” Durham said. “Our investigation has included developing information from other persons and entities, both in the U.S. and outside of the U.S. Based on the evidence collected to date, and while our investigation is ongoing, last month we advised the Inspector General that we do not agree with some of the report’s conclusions as to predication and how the FBI case was opened.”

These were Horowitz’s bottom line conclusions:

In July 2016, 3 weeks after then FBI Director James Comey announced the conclusion of the FBI’s “Midyear Exam” investigation into presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s handling of government emails during her tenure as Secretary of State, the FBI received reporting from a Friendly Foreign Government (FFG) that, in a May 2016 meeting with the FFG, Trump campaign foreign policy advisor George Papadopoulos “suggested the Trump team had received some kind of a suggestion” from Russia that it could assist in the election process with the anonymous release of information during the campaign that would be damaging to candidate Clinton and President Obama. Days later, on July 31, the FBI initiated the Crossfire Hurricane investigation that is the subject of this report.

As we noted last year in our review of the Midyear investigation, the FBI has developed and earned a reputation as one of the world’s premier law enforcement agencies in significant part because of its tradition of professionalism, impartiality, non-political enforcement of the law, and adherence to detailed policies, practices, and norms. It was precisely these qualities that were required as the FBI initiated and conducted Crossfire Hurricane. However, as we describe in this report, our review identified significant concerns with how certain aspects of the investigation were conducted and supervised, particularly the FBI’s failure to adhere to its own standards of accuracy and completeness when filing applications for Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) authority to surveil Carter Page, a U.S. person who was connected to the Donald J. Trump for President Campaign. We also identified what we believe is an absence of sufficient policies to ensure appropriate Department oversight of significant investigative decisions that could affect constitutionally protected activity.

The Opening of Crossfire Hurricane and the Use of Confidential Human Sources

The decision to open the Crossfire Hurricane investigation was made by the FBI’s then Counterintelligence Division (CD) Assistant Director (AD), E.W. “Bill” Priestap, and reflected a consensus reached after multiple days of discussions and meetings among senior FBI officials. We concluded that AD Priestap’s exercise of discretion in opening the investigation was in compliance with Department and FBI policies, and we did not find documentary or testimonial evidence that political bias or improper motivation influenced his decision. While the information in the FBI’s possession at the time was limited, in light of the low threshold established by Department and FBI predication policy, we found that Crossfire Hurricane was opened for an authorized investigative purpose and with sufficient factual predication.

However, we also determined that, under Department and FBI policy, the decision whether to open the Crossfire Hurricane counterintelligence investigation, which involved the activities of individuals associated with a national major party campaign for president, was a discretionary judgment call left to the FBI. There was no requirement that Department officials be consulted, or even notified, prior to the FBI making that decision. We further found that, consistent with this policy, the FBI advised supervisors in the Department’s National Security Division (NSD) of the investigation only after it had been initiated. As we detail in Chapter Two, high- level Department notice and approval is required in other circumstances where investigative activity could substantially impact certain civil liberties, and that notice allows senior Department officials to consider the potential constitutional and prudential implications in advance of these activities. We concluded that similar advance notice should be required in circumstances such as those that were present here.

Shortly after the FBI opened the Crossfire Hurricane investigation, the FBI conducted several consensually monitored meetings between FBI confidential human sources (CHS) and individuals affiliated with the Trump campaign, including a high-level campaign official who was not a subject of the investigation. We found that the CHS operations received the necessary approvals under FBI policy; that an Assistant Director knew about and approved of each operation, even in circumstances where a first-level supervisory special agent could have approved the operations; and that the operations were permitted under Department and FBI policy because their use was not for the sole purpose of monitoring activities protected by the First Amendment or the lawful exercise of other rights secured by the Constitution or laws of the United States. We did not find any documentary or testimonial evidence that political bias or improper motivation influenced the FBI’s decision to conduct these operations. Additionally, we found no evidence that the FBI attempted to place any CHSs within the Trump campaign, recruit members of the Trump campaign as CHSs, or task CHSs to report on the Trump campaign.

However, we are concerned that, under applicable Department and FBI policy, it would have been sufficient for a first-level FBI supervisor to authorize the sensitive domestic CHS operations undertaken in Crossfire Hurricane, and that there is no applicable Department or FBI policy requiring the FBI to notify Department officials of a decision to task CHSs to consensually monitor conversations with members of a presidential campaign. Specifically, in Crossfire Hurricane, where one of the CHS operations involved consensually monitoring a high-level official on the Trump campaign who was not a subject of the investigation, and all of the operations had the potential to gather sensitive information of the campaign about protected First Amendment activity, we found no evidence that the FBI consulted with any Department officials before conducting the CHS operations-and no policy requiring the FBI to do so. We therefore believe that current Department and FBI policies are not sufficient to ensure appropriate oversight and accountability when such operations potentially implicate sensitive, constitutionally protected activity, and that requiring Department consultation, at a minimum, would be appropriate.

The FISA Applications to Conduct Surveillance of Carter Page

One investigative tool for which Department and FBI policy expressly require advance approval by a senior Department official is the seeking of a court order under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). When the Crossfire Hurricane team first proposed seeking a FISA order targeting Carter Page in mid- August 2016, FBI attorneys assisting the investigation considered it a “close call” whether they had developed the probable cause necessary to obtain the order, and a FISA order was not requested at that time. However, in September 2016, immediately after the Crossfire Hurricane team received reporting from Christopher Steele concerning Page’s alleged recent activities with Russian officials, FBI attorneys advised the Department that the team was ready to move forward with a request to obtain FISA authority to surveil Page. FBI and Department officials told us the Steele reporting “pushed [the FISA proposal] over the line” in terms of establishing probable cause. FBI leadership supported relying on Steele’s reporting to seek a FISA order targeting Page after being advised of, and giving consideration to, concerns expressed by a Department attorney that Steele may have been hired by someone associated with a rival candidate or campaign.

The authority under FISA to conduct electronic surveillance and physical searches targeting individuals significantly assists the government’s efforts to combat terrorism, clandestine intelligence activity, and other threats to the national security. At the same time, the use of this authority unavoidably raises civil liberties concerns. FISA orders can be used to surveil U.S. persons, like Carter Page, and in some cases the surveillance will foreseeably collect information about the individual’s constitutionally protected activities, such as Page’s legitimate activities on behalf of a presidential campaign. Moreover, proceedings before the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC)-which is responsible for ruling on applications for FISA orders-are ex parte, meaning that unlike most court proceedings, the government is present but the government’s counterparty is not. In addition, unlike the use of other intrusive investigative techniques (such as wiretaps under Title III and traditional criminal search warrants) that are granted in ex parte hearings but can potentially be subject to later court challenge, FISA orders have not been subject to scrutiny through subsequent adversarial proceedings.

In light of these concerns, Congress through the FISA statute, and the Department and FBI through policies and procedures, have established important safeguards to protect the FISA application process from irregularities and abuse. Among the most important are the requirements in FBI policy that every FISA application must contain a “full and accurate” presentation of the facts, and that agents must ensure that all factual statements in FISA applications are “scrupulously accurate.” These are the standards for fill FISA applications, regardless of the investigation’s sensitivity, and it is incumbent upon the FBI to meet them in every application. That said, in the context of an investigation involving persons associated with a presidential campaign, where the target of the FISA is a former campaign official and the goal of the FISA is to uncover, among other things, information about the individual’s allegedly illegal campaign-related activities, members of the Crossfire Hurricane investigative team should have anticipated, and told us they in fact did anticipate, that these FISA applications would be subjected to especially close scrutiny.

Nevertheless, we found that members of the Crossfire Hurricane team failed to meet the basic obligation to ensure that the Carter Page FISA applications were “scrupulously accurate.” We identified significant inaccuracies and omissions in each of the four applications-7 in the first FISA application and a total of 17 by the final renewal application. For example, the Crossfire Hurricane team obtained information from Steele’s Primary Sub-source in January 2017 that raised significant questions about the reliability of the Steele reporting that was used in the Carter Page FISA applications. But members of the Crossfire Hurricane team failed to share the information with the Department, and it was therefore omitted from the three renewal applications. All of the applications also omitted information the FBI had obtained from another U.S. government agency detailing its prior relationship with Page, including that Page had been approved as an operational contact for the other agency from 2008 to 2013, and that Page had provided information to the other agency concerning his prior contacts with certain Russian intelligence officers, one of which overlapped with facts asserted in the FISA application.

As a result of the 17 significant inaccuracies and omissions we identified, relevant information was not shared with, and consequently not considered by, important Department decision makers and the court, and the FISA applications made it appear as though the evidence supporting probable cause was stronger than was actually the case. We also found basic, fundamental, and serious errors during the completion of the FBl’s factual accuracy reviews, known as the Woods Procedures, which are designed to ensure that FISA applications contain a full and accurate presentation of the facts.

We do not speculate whether the correction of any particular misstatement or omission, or some combination thereof, would have resulted in a different outcome. Nevertheless, the Department’s decision makers and the court should have been given complete and accurate information so that they could meaningfully evaluate probable cause before authorizing the surveillance of a U.S. person associated with a presidential campaign. That did not occur, and as a result, the surveillance of Carter Page continued even as the FBI gathered information that weakened the assessment of probable cause and made the FISA applications less accurate.

We determined that the inaccuracies and omissions we identified in the applications resulted from case agents providing wrong or incomplete information to Department attorneys and failing to identify important issues for discussion. Moreover, we concluded that case agents and SSAs did not give appropriate attention to facts that cut against probable cause, and that as the investigation progressed and more information tended to undermine or weaken the assertions in the FISA applications, the agents and SSAs did not reassess the information supporting probable cause. Further, the agents and SSAs did not follow, or even appear to know, certain basic requirements in the Woods Procedures. Although we did not find documentary or testimonial evidence of intentional misconduct on the part of the case agents who assisted NSD’s Office of Intelligence (01) in preparing the applications, or the agents and supervisors who performed the Woods Procedures, we also did not receive satisfactory explanations for the errors or missing information. We found that the offered explanations for these serious errors did not excuse them, or the repeated failures to ensure the accuracy of information presented to the FISC.

We are deeply concerned that so many basic and fundamental errors were made by three separate, hand-picked investigative teams; on one of the most sensitive FBI investigations; after the matter had been briefed to the highest levels within the FBI; even though the information sought through use of FISA authority related so closely to an ongoing presidential campaign; and even though those involved with the investigation knew that their actions were likely to be subjected to close scrutiny. We believe this circumstance reflects a failure not just by those who prepared the FISA applications, but also by the managers and supervisors in the Crossfire Hurricane chain of command, including FBI senior officials who were briefed as the investigation progressed. We do not expect managers and supervisors to know every fact about an investigation, or senior leaders to know all the details of cases about which they are briefed. However, especially in the FBl’s most sensitive and high-priority matters, and especially when seeking court permission to use an intrusive tool such as a FISA order, it is incumbent upon the entire chain of command, including senior officials, to take the necessary steps to ensure that they are sufficiently familiar with the facts and circumstances supporting and potentially undermining a FISA application in order to provide effective oversight consistent with their level of supervisory responsibility. Such oversight requires greater familiarity with the facts than we saw in this review, where time and again during OIG interviews FBI managers, supervisors, and senior officials displayed a lack of understanding or awareness of important information concerning many of the problems we identified.

In the preparation of the FISA applications to surveil Carter Page, the Crossfire Hurricane team failed to comply with FBI policies, and in so doing fell short of what is rightfully expected from a premier law enforcement agency entrusted with such an intrusive surveillance tool. In light of the significant concerns identified with the Carter Page FISA applications and the other issues described in this report, the OIG today initiated an audit that will further examine the FBI’s compliance with the Woods Procedures in FISA applications that target U.S. persons in both counterintelligence and counterterrorism investigations. We also make the following recommendations to assist the Department and the FBI in avoiding similar failures in future investigations.

The IG’s recommendations:

1. The Department and the FBI should ensure that adequate procedures are in place for the Office of Intelligence (01) to obtain all relevant and accurate information, including access to Confidential Human Source (CHS) information, needed to prepare FISA applications and renewal applications. This effort should include revising:

a. the FISA Request Form: to ensure information is identified for 01: (i) that tends to disprove, does not support, or is inconsistent with a finding or an allegation that the target is a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power, or (ii) that bears on the reliability of every CHS whose information is relied upon in the FISA application, including all information from the derogatory information sub-file, recommended below;

b. the Woods Form: (i) to emphasize to agents and their supervisors the obligation to re-verify factual assertions repeated from prior applications and to obtain written approval from CHS handling agents of all CHS source characterization statements in applications, and (ii) to specify what steps must be taken and documented during the legal review performed by an FBI Office of General Counsel (OGC) line attorney and SES- level supervisor before submitting the FISA application package to the FBI Director for certification;

c. the FISA Procedures: to clarify which positions may serve as the supervisory reviewer for OGC; and

d. taking any other steps deemed appropriate to ensure the accuracy and completeness of information provided to 01.2. The Department and FBI should evaluate which types of Sensitive Investigative Matters (SIM) require advance notification to a senior Department official, such as the Deputy Attorney General, in addition to the notifications currently required for SIMs, especially for case openings that implicate core First Amendment activity and raise policy considerations or heighten enterprise risk, and establish implementing policies and guidance, as necessary.

3. The FBI should develop protocols and guidelines for staffing and administrating any future sensitive investigative matters from FBI Headquarters.

4. The FBI should address the problems with the administration and assessment of CHSs identified in this report and, at a minimum, should:

a. revise its standard CHS admonishment form to include a prohibition on the disclosure of the CHS’s relationship with the FBI to third parties absent the FBI’s permission, and assess the need to include other admonishments in the standard CHS admonishments;

b. develop enhanced procedures to ensure that CHS information is documented in Delta, including information generated from Headquarters-led investigations, substantive contacts with closed CHSs (directly or through third parties), and derogatory information. We renew our recommendation that the FBI create a derogatory information sub-file in Delta;

c. assess VMU’s practices regarding reporting source validation findings and non-findings;

d. establish guidance for sharing sensitive information with CHSs;

e. establish guidance to handling agents for inquiring whether their CHS participates in the types of groups or activities that would bring the CHS within the definition of a “sensitive source,” and ensure handling agents document (and update as needed) those affiliations and any others voluntarily provided to them by the CHS in the Source Opening Communication, the “Sensitive Categories” portion of each CHS’s Quarterly Supervisory Source Report, the “Life Changes” portion of CHS Contact Reports, or as otherwise directed by the FBI so that the FBI can assess whether active CHSs are engaged in activities (such as political campaigns) at a level that might require re-designation as a “sensitive source” or necessitate closure of the CHS; and

f. revise its CHS policy to address the considerations that should be taken into account and the steps that should be followed before and after accepting information from a closed CHS indirectly through a third party.5. The Department and FBI should clarify the following terms in their policies:

a. assess the definition of a “Sensitive Monitoring Circumstance” in the AG Guidelines and the FBI’s DIOG to determine whether to expand its scope to include consensual monitoring of a domestic political candidate or an individual prominent within a domestic political organization, or a subset of these persons, so that consensual monitoring of such individuals would require consultation with or advance notification to a senior Department official, such as the Deputy Attorney General; and

b. establish guidance, and include examples in the DIOG, to better define the meaning of the phrase “prominent in a domestic political organization” so that agents understand which campaign officials fall within that definition as it relates to “Sensitive Investigative Matters,” “Sensitive UDP,” and the designation of “sensitive sources.” Further, if the Department expands the scope of “Sensitive Monitoring Circumstance,” as recommended above, the FBI should apply the guidance on “prominent in a domestic political organization” to “Sensitive Monitoring Circumstance” as well.6. The FBI should ensure that appropriate training on DIOG § 4 is provided to emphasize the constitutional implications of certain monitoring situations and to ensure that agents account for these concerns, both in the tasking of CHSs and in the way they document interactions with and tasking of CHSs.

7. The FBI should establish a policy regarding the use of defensive and transition briefings for investigative purposes, including the factors to be considered and approval by senior leaders at the FBI with notice to a senior Department official, such as the Deputy Attorney General.

8. The Department’s Office of Professional Responsibility should review our findings related to the conduct of Department attorney Bruce Ohr for any action it deems appropriate. Ohr’s current supervisors in the Department’s Criminal Division should also review our findings related to Ohr’s performance for any action they deem appropriate.

9. The FBI should review the performance of all employees who had responsibility for the preparation, Woods review, or approval of the FISA applications, as well as the managers, supervisors, and senior officials in the chain of command of the Carter Page investigation, for any action deemed appropriate.

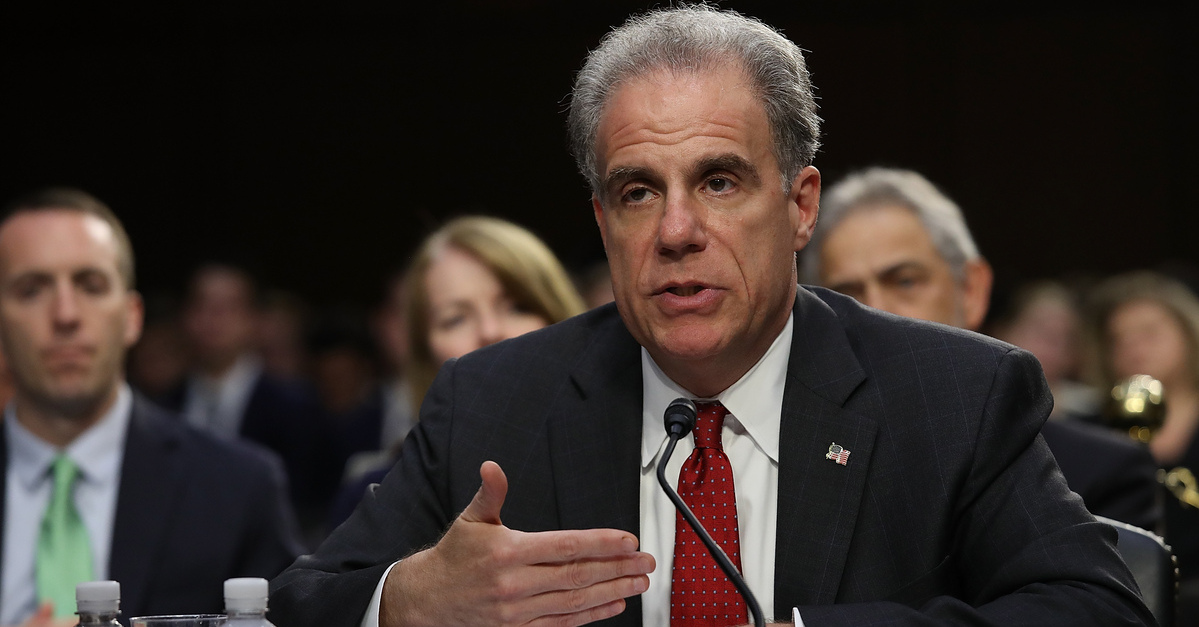

[Image via Win McNamee/Getty Images]