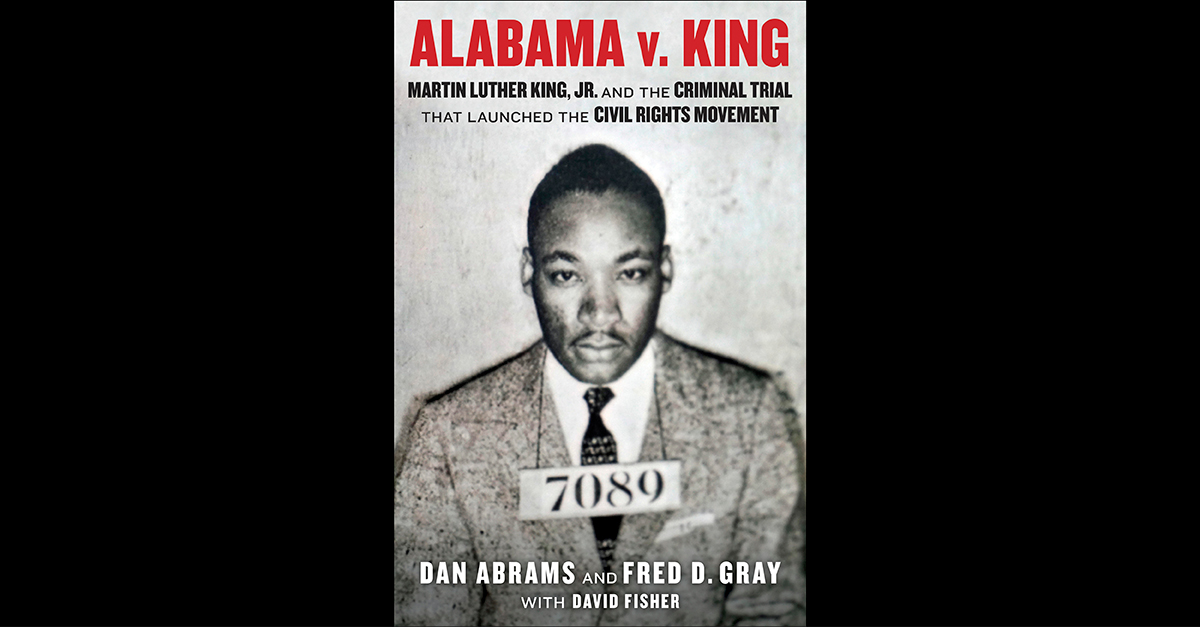

The coming new book Alabama v. King: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Criminal Trial that Launched the Civil Rights Movement takes a look at the “forgotten” criminal trial of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the wake of Rosa Parks‘ refusal in 1955 to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Law&Crime founder Dan Abrams is co-authoring the book on the historic case with Fred Gray, attorney for both Parks and Dr. King.

The book from publisher HarperCollins, scheduled to hit shelves on May 24, provides relevant context about the lead-up to the protest, both about Parks and the broader and burgeoning civil rights movement. A book excerpt recounts key events this way:

At about 9:15 pm on January 30, 1956, 27-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. was advocating non-violent protest to approximately two thousand people at the cavernous First Baptist Church. Dr. King told the enthralled audience, “If all I have to pay is going to jail a few times and getting about 20 threatening calls a day. . . I think that is a very small price to pay for what we are fighting for.” Little could he know that as he spoke, that price was becoming significantly higher.

A white supremacist had driven to his home that night, walked up half the steps of his white clapboard house in a quiet neighborhood, and tossed a live stick of dynamite onto the front porch. His wife, Coretta Scott King, and a friend had been in the living room and their newborn daughter, Yolanda, asleep in a back room. When the dynamite exploded a few moments later, windows were blown out and portions of the house destroyed or in shambles.

Upon hearing of the incident, King immediately rushed home and was relieved to find his wife, her friend and his daughter all uninjured. A furious and fearful crowd of about three hundred quickly gathered to support the King family and with the remnant smell of explosives still wafting through the night air, Dr. King stepped out onto his only partially standing porch and declared: “We believe in law and order. Don’t get your weapons. . . We are not advocating violence. We want to love our enemies.” With those words, a potentially volatile situation had been diffused.

The local authorities never arrested the perpetrator of the crime, but less than two months later they did arrest Dr. King for organizing the peaceful protests he was championing the night his house was bombed. The trial that followed would introduce the young minister to America.

It had required an extraordinary, unexpected and fortuitous chain of events to place the young Dr. King in the spotlight of history. It was not a role he had pursued. “When Martin Luther King came to Montgomery in 1953,” Fred Gray, his friend and first defense attorney remembers, “He didn’t have civil rights on his mind. In fact, the preacher before him had gotten run out of town because he was too liberal.”

But after civil right activist Rosa Parks was arrested on December 1, 1955 for violating a city statute by refusing to give up her seat on a crowded bus to a white person, a small group of Montgomery’s leading Black citizens and ministers had urged a one-day bus boycott to protest the way Black Americans were being treated on public transit. The protest was scheduled for December 5th, the day of Parks’ trial. “This was a long time coming,” explained Fred Gray. “This wasn’t just an isolated incident. We had been complaining about the way Black people were treated on the buses for a long time. But the bus company had done nothing at all about it. We would have settled for minor changes; instead, they just ignored us. They treated us like we had no rights. So when Mrs. Parks was arrested the community just said, this is it. We’re going to do something about it right now. They are going to give us respect or we are not going to continue riding their buses.”

At her 30-minute trial on December 5th, Rosa Parks pled not guilty to charges of disorderly conduct and violating a local statute. Fred Gray defended her. She was convicted and fined $10, plus $4 in court costs. Gray immediately appealed the conviction. But by that time the protest had begun.

Parks’ arrest and conviction inspired the “Montgomery Bus Boycott” and a speech Dr. King gave which animated protests against segregation in the Deep South.

“Mrs. Rosa Parks is a fine person. And, since it had to happen, I’m happy that it happened to a person like Mrs. Parks, for nobody can doubt the boundless outreach of her integrity. Nobody can doubt the height of her character nobody can doubt the depth of her Christian commitment and devotion to the teachings of Jesus,” he said in the speech. “And I’m happy since it had to happen, it happened to a person that nobody can call a disturbing factor in the community. Mrs. Parks is a fine Christian person, unassuming, and yet there is integrity and character there. And just because she refused to get up, she was arrested.”

“And you know, my friends, there comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression,” he added.

Dr. King, then a 27-year-old minister, would soon be in legal trouble himself as prosecutors blamed him for being the leader of the bus boycott in violation of an anti-boycott statute.

As King’s first lawyer Fred Gray remembers it, this moment in history was what plucked Dr. King from relative anonymity and set him on the path to becoming a civil rights icon.

“It certainly is accurate to say that none of the people who picked him thought of him as someone who would lead Black folks all over the country. We were just dealing with the situation on the buses in Montgomery. It was only later that we understood that this sort of casual selection had made all the difference in the world,” Gray said.

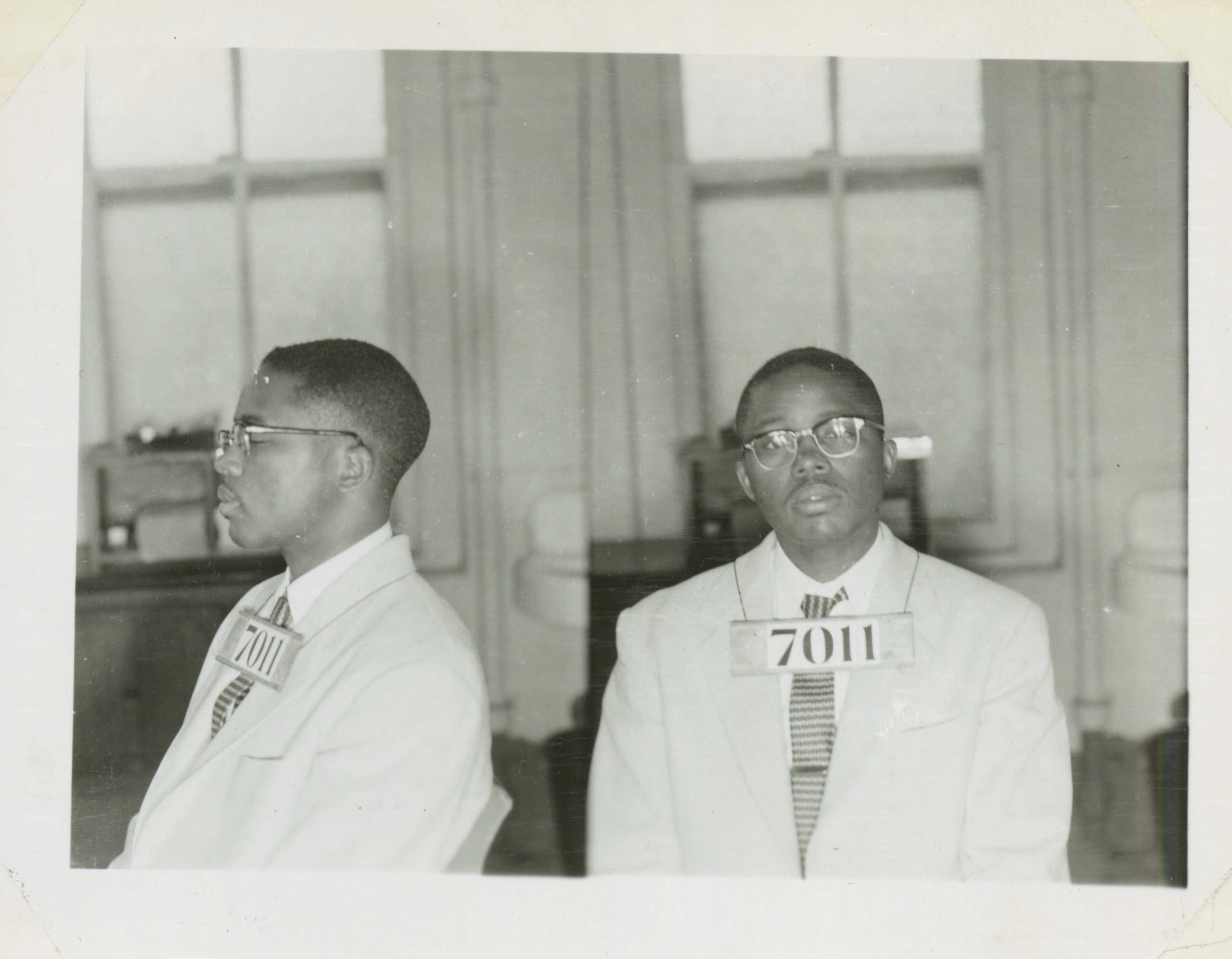

Fred Gray mugshot, Montgomery County Archives

Gray was 25 years old at the time and described having “legal problems almost every day,” with Dr. King “in the middle of every one of them.”

Then came Dr. King’s trial and eventual conviction.

Eighty-nine were arrested, but Dr. King was prosecuted as the leader of the “Montgomery Bus Boycott.” And yet Gray didn’t have concerns about King testifying in his own defense at trial. He described a client who would accept legal advice, who was knowledgeable of the law, who was wary of prosecutorial traps, and who had an ability to be authentic and confident on the stand.

“During the trial we would discuss legal strategy and he would state his opinions but generally he accepted advice. Our primary goal was that whatever the outcome of the case, that Martin Luther King would come out of it a winner. He had never testified in a trial before, but I had great confidence in him,” Gray said. “We had prepared him well for both his direct testimony and cross-examination: Dr. King understood what the law was, what the facts were, what our theory of the case was and what the prosecution would try to do. Their goal was to prove that he was the leader, the man making decisions, rather than the spokesman for all of the others.”

“He was aware of the legal traps that Mr. Thetford would set for him and how to avoid them. He sat quietly through all the testimony, listening attentively. After each day we would all get together in my office to review the day’s proceedings and plan for the following day. And while we never told him how to respond or what to say, we never rehearsed. But Dr. King understood that sometimes there was a difference between the law and justice, and he had spent his whole life believing in justice for our community,” he added. “He was firm about that, and that made him completely confident. He wasn’t the slightest bit nervous as he took the stand. He knew what they were going to try to get him to say and he knew what we wanted him to say. I suspect many of the people in that courtroom were far more nervous for him than he felt.”

In addition to Gray’s firsthand insight and accounts, the book accesses primary sources, such as transcripts of Dr. King’s trial testimony, as well as testimony of Black witnesses, to bring readers in 2022 back to the 1950s in Montgomery, Alabama.

Joining Abrams and Gray as co-author is David Fisher. Abrams and Fisher have also co-authored several other books, New York Times bestsellers among them, on John Adams, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and Jack Ruby.

[Image via HarperCollins]