Police lacked reasonable suspicion to stop the late Elijah McClain, with one officer refusing to wait more than 10 seconds to literally get their hands on the 23-year-old in a confrontation before his death, an independent commission in Colorado found on Monday.

“In interviews with the Aurora Police Department’s Major Crime/Homicide Unit (‘Major Crime’) investigators, none of the officers articulated a crime that they thought Mr. McClain had committed, was committing, or was about to commit,” the three-member panel from the city of Aurora, Colo. found in a 157-page report. “They provided the following reasons, none of which under the prevailing case law is sufficient to establish reasonable suspicion: Mr. McClain was acting ‘suspicious,’ was wearing a mask and waving his arms, and he was in an area with a ‘high crime rate.'”

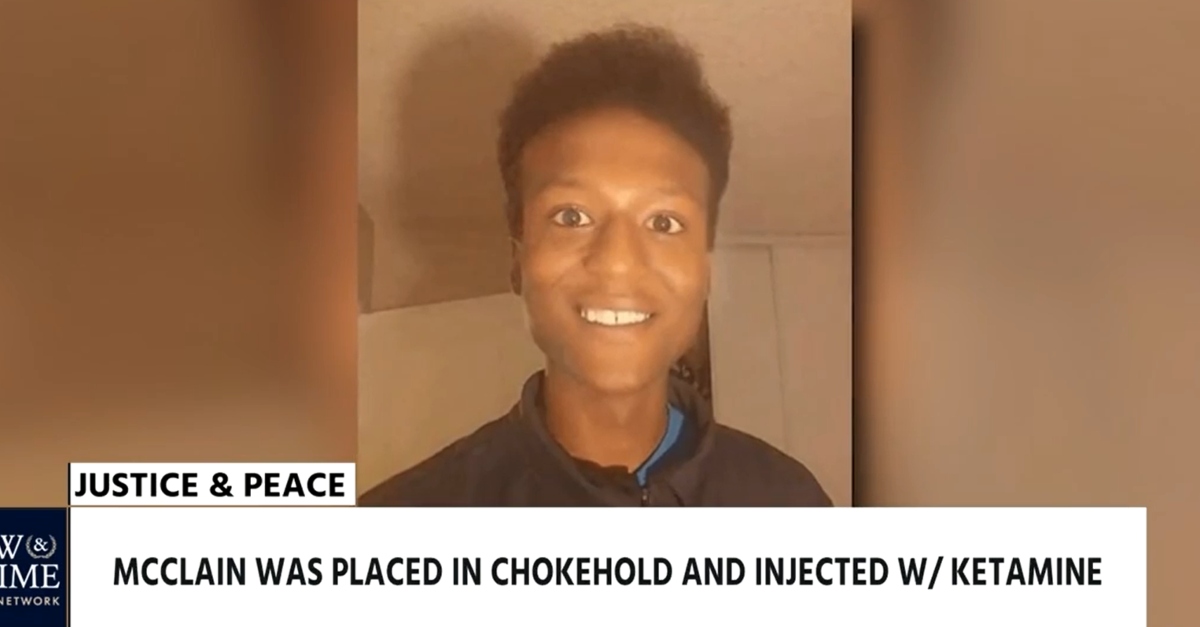

As previously reported, police confronted McClain on August 24, 2019 after a caller reported a suspicious person wearing a ski mask. Asked if there were weapons involved, or if anyone was in danger, the person said: “No.”

According to the report, Officer Nathan Woodyard escalated the situation, putting his hands on McClain within 10 seconds of exiting his patrol vehicle.

After the arrival of Officers Jason Rosenblatt and Randy Roedema, Woodyard decided to frisk McClain for weapons.

The officers surrounded Mr. McClain, with one officer holding each of Mr. McClain’s arms. Mr. McClain, according to the officers, was “tensing up” and they asked him repeatedly to “relax,” cooperate, and “stop tensing up.” One officer told him, “this isn’t going to go well.”

After officers decided to arrest McClain, Rosenblatt allegedly applied the initial carotid hold, a grappling technique that cuts off blood to the brain. The panel found that this took place after quoting Roedema telling his colleague that McClain “grabbed your gun.” Woodyard applied the second carotid hold, according to the report:

Positioned behind Mr. McClain, who was lying on his side, Officer Woodyard attempted to apply a carotid control hold. Although it is unclear precisely how long Officer Woodyard applied the hold, on the body worn camera footage an officer can be heard asking “Is he out?” and two other officers responding “no,” and “not yet.” Officer Roedema said he saw Mr. McClain’s eyes “roll back and his head starting to go limp,” and he instructed Officer Woodyard to release the hold.

Taking Major Crimes investigators to task in the investigation of the aftermath, the panel found that the detectives’ questioning did not distinguish between the perceived threat when McClain was standing or when he was on the ground.

“The record therefore does not provide evidence of the officers’ perception of a threat that would justify Officer Woodyard’s carotid hold, which caused Mr. McClain to either partially or fully lose consciousness,” the report stated.

The panel accused Major Crimes of giving questions to the officers that often appeared to “elicit specific exonerating ‘magic language’ found in court rulings.” The District Attorney for Colorado’s 17th Judicial District and the Force Review Board relied on the Major Crimes report, though that report failed to be neutral and it ignored “contrary evidence,” according to the panel’s findings.

The report did not spare paramedics from criticism for the 500 milligram dose of the sedative ketamine that was used on McClain. According to the report, Aurora Fire Lt. Peter Cichuniec estimated that McClain weighed 190 pounds. The autopsy determined that the man was only 140 pounds, however. Parademics failed to independently substantiate McClain’s diagnosis “excited delirium” before administering the drug, the panel found, elaborating upon the episode in this passage:

As stated above, during the time that Aurora Fire was on the scene, Mr. McClain’s behavior in the presence of EMS should have raised questions for EMS personnel as to whether excited delirium was the appropriate diagnosis.

Aurora Fire protocols permitted the administration of ketamine for a patient with symptoms of excited delirium and where there were concerns regarding the patient’s or others’ safety. Aurora EMS determined it was appropriate to administer ketamine to Mr. McClain despite the fact that he did not appear to be offering meaningful resistance in the presence of EMS personnel. In addition, EMS administered a ketamine dosage based on a grossly inaccurate and inflated estimate of Mr. McClain’s size. Higher doses can carry a higher risk of sedation complications, for which this team was not clearly prepared.

McClain’s death captured national attention as part of the ongoing debate on how law enforcement treats people of color, especially Black men like him. No charges have been filed in McClain’s death. A prosecutor previously said he could not prove the McClain’s death was a homicide. The panel did not determine if any bias played a role in the events of August 24, 2019.

A prosecutorial decision is outside the scope of the commission’s investigation, but the panel advised a series of reforms in response to this case.

“The national debate concerning the role of law enforcement in communities of color includes a robust discussion of implicit or unconscious bias,” the panel wrote. “In looking at this single incident, the Panel has insufficient information to determine what role, if any, bias played in Aurora Police officers’ and EMS personnel’s encounter with Mr. McClain. However, research indicates that factors such as increased perception of threat, perception of extraordinary strength, perception of higher pain tolerance, and misperception of age and size can be indicators of bias. We urge that the City assess its efforts to ensure bias-free policing, implicit or otherwise.”

The panelists were Jonathan Smith, the executive director of the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs and former head of special litigation for the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division; former Tuscon police chief Roberto Villaseñor, now a founding partner of a policing consultant 21CP Solutions; and Dr. Melissa Costello, a practicing emergency medicine physician and EMS medical director based in Mobile, Alabama.

[Screengrab via Law&Crime Network]