Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas agreed with the 7-2 majority on Monday in Gamble v. U.S., declining to overturn the “longstanding dual-sovereignty doctrine.” Thomas penned a concurring opinion that spanned 17 pages. In that opinion, he took took direct aim at stare decisis — the doctrine of respect for and deference to precedent.

After Justice Samuel Alito delivered the opinion of the Court (with only Justices Neil Gorsuch and Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissenting), Justice Thomas revealed that he agreed with the majority despite his “initial skepticism.” At root, the decision means that the Court holds that individuals can be prosecuted by the federal government and states without violating the double jeopardy clause of the Fifth Amendment (“nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb”). Why? Because “where there are two sovereigns, there are two laws and two ‘offences” — that is, they aren’t “same offences.”

Now that this was out of the way, Thomas penned a term-paper of sorts on the “proper role of the doctrine of stare decisis.”

Thomas proposed that the Court should “restore our stare decisis jurisprudence to ensure that we exercise ‘mer[e] judgment,’ which can be achieved through adherence to the correct, original meaning of the laws we are charged with applying.”

“In my view, anything less invites arbitrariness into judging,” Thomas added.

Thomas said that this “arbitrariness” results in an illusion of consistency prone to outcomes justices prefer — in direct conflict with the Court’s constitutionally mandated duty: “[F]aithfully interpreting the Constitution and the laws enacted by those [political] branches.” As he explained his reasoning, Thomas made sure to cite to Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which famously reaffirmed Roe v. Wade (Law&Crime’s Elura Nanos opined elsewhere that Thomas was “laying groundwork for a Roe v. Wade reversal”):

The Court currently views stare decisis as a “‘principle of policy’” that balances several factors to decide whether the scales tip in favor of overruling precedent. Citizens United v. Federal Election Comm’n, 558 U. S. 310, 363 (2010) (quoting Helvering v. Hallock, 309 U. S. 106, 119 (1940)). Among these factors are the “workability” of the standard, “the antiquity of the precedent, the reliance interests at stake, and of course whether the decision was well reasoned.” Montejo v. Louisiana, 556 U. S. 778, 792– 793 (2009). The influence of this last factor tends to ebb and flow with the Court’s desire to achieve a particular end, and the Court may cite additional, ad hoc factors to reinforce the result it chooses. But the shared theme is the need for a “special reason over and above the belief that a prior case was wrongly decided” to overrule a precedent. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U. S. 833, 864 (1992). The Court has advanced this view of stare decisis on the ground that “it promotes the evenhanded, predictable, and consistent development of legal principles” and “contributes to the actual and perceived integrity of the judicial process.” Payne v. Tennessee, 501 U. S. 808, 827 (1991).

This approach to stare decisis might have made sense in a common-law legal system in which courts systematically developed the law through judicial decisions apart from written law. But our federal system is different. The Constitution tasks the political branches—not the Judiciary—with systematically developing the laws that govern our society. The Court’s role, by contrast, is to exercise the “judicial Power,” faithfully interpreting the Constitution and the laws enacted by those branches.

Thomas later elaborated on why he has little to no faith in the above-described “multifactor approach to stare decisis“:

[T]he Court’s multifactor approach to stare decisis invites conflict with its constitutional duty. Whatever benefits may be seen to inhere in that approach—e.g., “stability” in the law, preservation of reliance interests, or judicial “humility,”—they cannot overcome that fundamental flaw. In any event, these oft-cited benefits are frequently illusory. The Court’s multifactor balancing test for invoking stare decisis has resulted in policy-driven, “arbitrary discretion.” The Federalist No. 78, at 471. The inquiry attempts to quantify the unquantifiable and, by frequently sweeping in subjective factors, provides a ready means of justifying whatever result five Members of the Court seek to achieve.

Rather than endorsing the status quo, Thomas offered a “simple” rule.

“When faced with a demonstrably erroneous precedent, my rule is simple: We should not follow it. This view of stare decisis follows directly from the Constitution’s supremacy over other sources of law—including our own precedents,” Thomas wrote. “That the Constitution outranks other sources of law is inherent in its nature.”

In closing, Thomas reiterated that the Supreme Court must “interpret the law” by “adher[ing] to the original meaning of the text.” As he did so, Thomas connected his thoughts on stare decisis to the double jeopardy matter at hand.

“For that reason, we should not invoke stare decisis to uphold precedents that are demonstrably erroneous,” he said. “Because petitioner and the dissenting opinions have not shown that the Court’s dual-sovereignty doctrine is incorrect, much less demonstrably erroneous, I concur in the majority’s opinion.”

SCOTUS ruling on Gamble v. U.S. by Law&Crime on Scribd

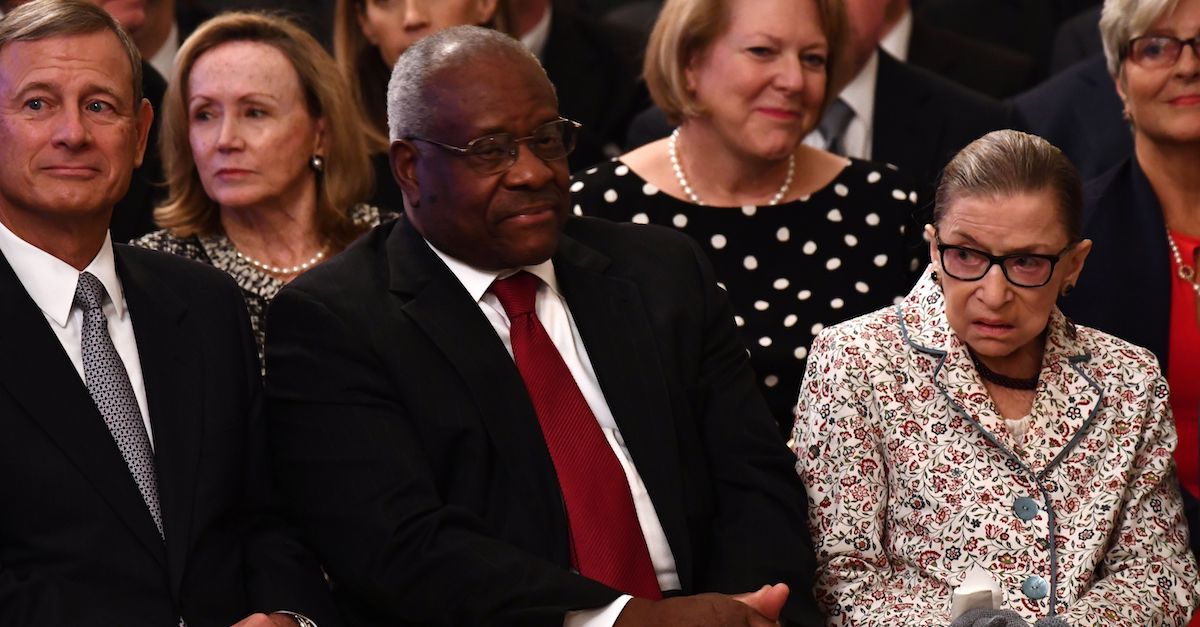

[Image via Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images]