Deutsche Bank on Tuesday agreed to a $150 million settlement over its relationship with since-deceased sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, shining a light on the German-based bank’s consistent failure to comply with financial regulations concerning millions of dollars of suspicious transactions. But the details contained in the blunt consent order between the bank and New York state financial regulators may potentially provide prosecutors with a new route for unearthing vital information pertaining to Epstein’s alleged criminal network.

According to the agreement, an unnamed personal attorney working for Epstein made 97 separate cash withdrawals from Epstein’s accounts at the same Manhattan location between 2013-2017. The transactions, which occurred two to three times per month, were all in the amount of $7,500, Deutsche Bank’s limit for third-party withdrawals.

“Under federal regulations, banks and other financial institutions must file Currency Transaction Reports (‘CTRs’) with the U.S. Treasury Department when there are cash transactions with an individual in excess of $10,000 in one day. Breaking up transactions to avoid the CTR reporting is a criminal offense commonly referred to as ‘structuring,’” the agreement stated.

As attorney Adrienne Lawrence noted, this type of conduct is a classic “indicator of money laundering.”

https://twitter.com/AdrienneLaw/status/1280520103042224131

The term “smurfing” refers to a common “structuring” technique where a money launderer employs individuals, or “smurfs,” to make unlawful transactions.

Furthermore, on at least two occasions, Epstein’s attorney also inquired how he could “withdraw cash on behalf of Mr. Epstein without triggering an alert.”

Former federal prosecutor Renato Mariotti, a CNN legal analyst, pointed out that prosecutors in the Southern District of New York (SDNY) could very likely use this information against this unnamed lawyer to make him cooperate with their investigation into Epstein’s other associates.

“Epstein’s attorney should be concerned about his own liability, given that he asked how to evade requirements. I would not be surprised if SDNY federal prosecutors tried to put pressure on this attorney in order to convince him to cooperate against Epstein’s other associates,” Mariotti wrote. “But any cooperation would be complicated by potential attorney-client privilege issues. I’ve prosecuted lawyers (and later represented lawyers who were under investigation), and prosecuting a lawyer is never easy. Immunity in exchange for the lawyer’s cooperation is a possibility, depending on what the lawyer did and how helpful he can be.”

In an interview with Law&Crime, CNN legal analyst Elie Honig, a former SDNY prosecutor, said he “largely agrees” with Mariotti’s take.

“Basically, anything that will give SDNY leverage can potentially be used to flip those who may have been involved in criminal activity,” Honig said. “If you have a lawyer who was intentionally breaking off transactions to avoid triggering reporting requirements, that’s a violation of federal law, which is certainly something that could be used as leverage to flip somebody.”

Honig also explained that while attorney-client privilege would certainly complicate the matter, that privilege would not attach to criminal conduct.

“There’s a crime-fraud exception to attorney-client privilege, meaning that if the conversations were in furtherance of a contemplated or ongoing crime, then the content of those conversations are no longer protected by privilege,” Honig added.

Former federal and state prosecutor Daniel R. Alonso suggested SDNY was likely already investigating the unnamed attorney.

“Very true, and note that structuring is also used very frequently to establish probable cause to obtain search warrants,” Alonso said. “Given that we now know about this, it is likely the government has been investigating this lawyer for some time.”

According to the consent agreement, which did not sugarcoat Deutsche Bank’s turning of a blind eye to Epstein, the bank properly classified Epstein as a “high-risk” client but didn’t take necessary precautions and didn’t examine suspicious transactions associated with exorbitant cash spending.

“The Bank was well aware not only that Mr. Epstein had pled guilty and served prison time for engaging in sex with a minor but also that there were public allegations that his conduct was facilitated by several named coconspirators. Despite this knowledge, the Bank did little or nothing to inquire into or block numerous payments to named co-conspirators, and to or on behalf of numerous young women, or to inquire how Mr. Epstein was using, on average, more than $200,000 per year in cash,” the agreement stated.

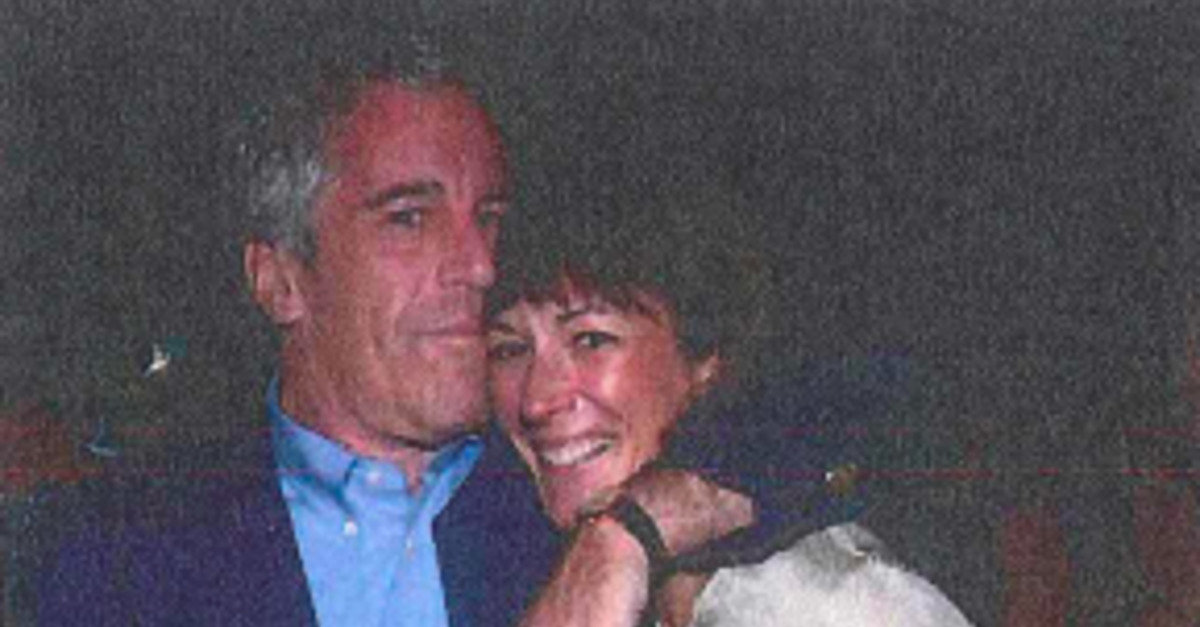

[image via DOJ]