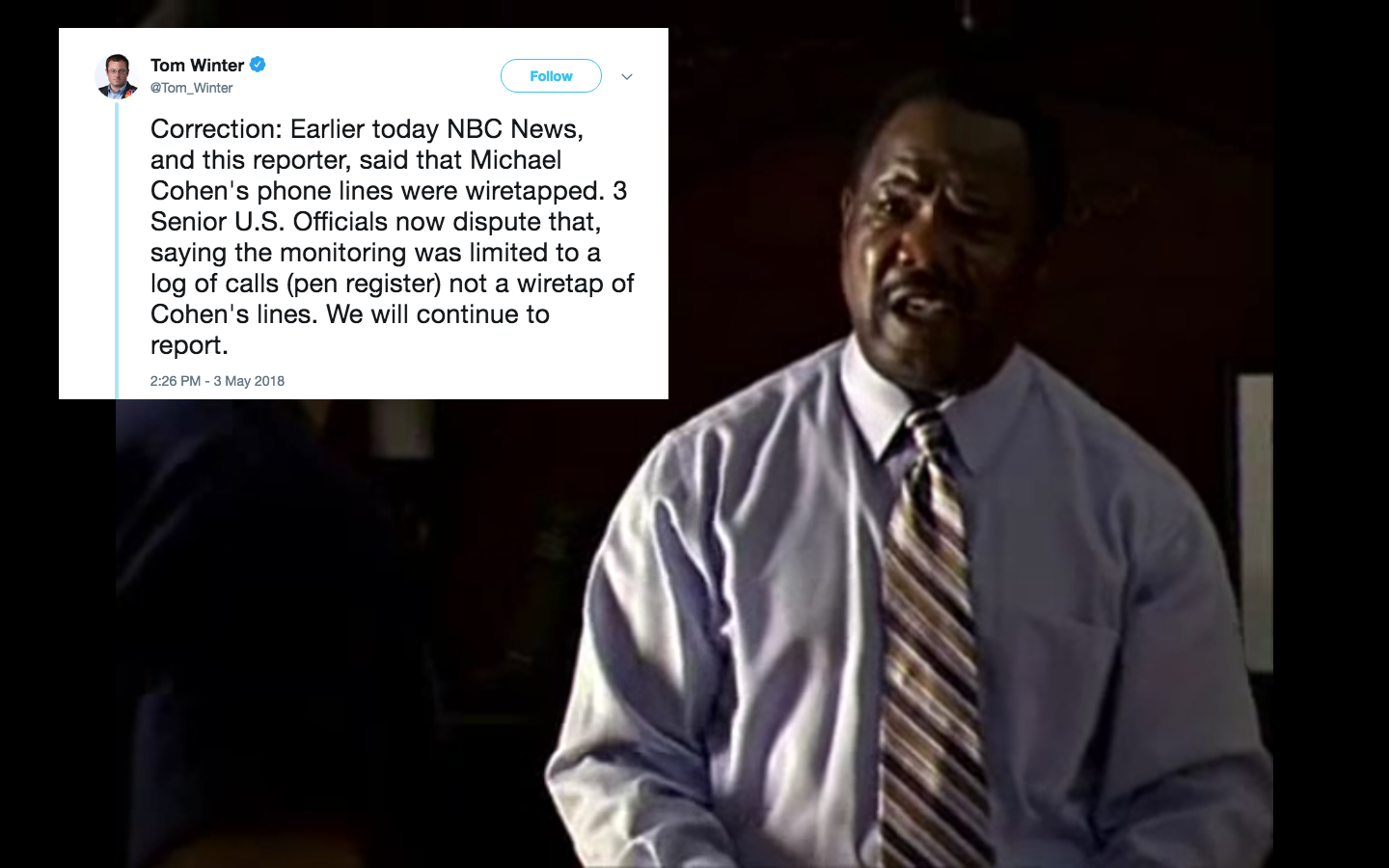

NBC News did almost everything in its power to support a suggested name change to “Fake News” on Thursday.

Based on two anonymous sources, journalists Tom Winter and Julia Ainsley originally reported that President Donald Trump‘s friend, attorney and fixer Michael Cohen was recently wiretapped by federal investigators.

A couple of late-day corrections revealed this story wasn’t actually true. Like, at all.

NBC’s erroneous wiretapping story dictated an entire day’s worth of press coverage based on the virtue of being wrong–an entire day’s worth of coverage that also happened to have knocked Rudy Giuliani‘s controversial comments regarding Stormy Daniels completely off the news cycle. Ho hum.

So, what’s the difference between a pen register and a wiretap? Quite a bit. But first of all, it’s become necessary to correct NBC for even minor faults here. Here’s the key graf from NBC’s updated story:

The calls are logged by what is commonly referred to as a pen register, which records the number of the phone that made the call and the number that received it, but does not record the contents of any conversation.

This is still wrong. As one U.S. district court noted, “Basically, a pen register is a device or process which records the telephone numbers of outgoing calls; the trap and trace device captures the telephone numbers of incoming calls.” So, what NBC has described is a pen/trap situation–not simply a pen register.

Federal authority to conduct the pen/trap form of electronic surveillance is codified at 18 U.S.C. §§ 3121–3127.

Pen/trap orders allow the government to obtain communications metadata–like the phone numbers of incoming and outgoing calls, or email addresses of senders and recipients. Pen/trap orders do not allow the government to listen in on the actual contents of a call or read the actual contents of an email or text.

The statute on point stipulates that federal courts must issue temporary orders which authorize the installation and use of pen/trap devices–typically these orders are in effect for 60 days. To obtain such an order, the government must certify “the information is likely to be obtained by such installation and use is relevant to an ongoing criminal investigation.”

This evidentiary standard for the government to obtain a pen/trap order is much lower than that required for a true-blue wiretap. In order to obtain a pen/trap order, the government must allege “specific and articulable facts.” This is a legal standard of proof less than probable cause. In other words, to conduct pen/trap surveillance, the government must be able to describe in detail what caused them to think criminal activity might be afoot. TL;DR–pen/trap orders aren’t very hard for the government to get.

The statutory authority for a federal wiretap order is codified at 18 U.S.C. §§ 2510–2522.

Wiretap orders are part of the media-mediated lore surrounding American criminal justice and injustice. An entire HBO series was based on wiretap orders or the lack thereof. Many people probably think they understand them–and quite a few of them apparently work at NBC News.

The Wiretap Act allows the government to apply for a “Title III” order which would authorize the real-time collection of wire, oral or electronic communications. Voices on the line. The words in an email or text. Etc.

Wiretap authorizations don’t last as long as pen/trap orders. The federal statute here requires the government to re-apply for an additional interception period every 30 days–such periods are typically no longer than 30 days–but this can sometimes be extended. Additionally, the government is mandated to “minimize” the amount of data they collect that’s not directly related to their order–or to stop collecting communications entirely once they get they’re looking for.

The evidentiary standard for a wiretap order is probable cause. This means the government must show a judge that the phone line or email account they want to wiretap is being used, or are about to be used, in connection with the commission” of the offense believed to be occurring. Probable cause is considered a fairly exacting standard in theory, but reality has a way of neatly binning legalistic mythology: whereas FISA Courts approve 99 percent of wiretap applications, Article III courts tend to approve even more.

Another way to consider the distinction here is that pen/trap orders are oftentimes precursors to wiretaps. Or, as USC Gould Law Professor Orin Kerr noted:

And another way to understand NBC’s massive flop here is: (1) say I called my brother early in the morning to tell them that my parents died in a car crash but; (2) sometime after Jeopardy aired I called back to say they had simply gone to Whataburger to get breakfast.

[image via screengrab/HBO]