Blocking Julian Assange’s extradition to the United States, a U.K. judge found on the Monday that the WikiLeaks founder’s psyche may not be able to handle the possibility of imprisonment for the rest of his life.

“I am as confident as a psychiatrist ever can be that, if extradition to the United States were to become imminent, Mr. Assange will find a way of suiciding,” Assange’s psychiatrist Michael Kopelman is quoted as saying in the 132-page judgment.

District Judge Vanessa Baraitser decisively rejected Assange’s depiction as the target of a politically motivated prosecution, but she had been troubled by reports that the WikiLeaks founder told his psychiatrist he thought about suicide “hundreds of times a day.”

“The auditory hallucinations were much less prominent and less troubling and the somatic hallucinations had been abolished,” the judgment continues. “His symptoms in December 2019 included loss of sleep, loss of weight, impaired concentration, a feeling of often being on the verge of tears, and a state of acute agitation in which he was pacing his cell until exhausted, punching his head or banging it against a cell wall.”

If extradited and convicted, the 49-year-old Assange could spend the rest of his natural life in a United States prison. He faces 17 charges related largely to a massive cache of military and diplomatic files disclosed to him by former Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning.

The Department of Justice said that it will continue to seek Assange’s extradition on appeal.

“While we are extremely disappointed in the court’s ultimate decision, we are gratified that the United States prevailed on every point of law raised,” the department said in a statement. “In particular, the court rejected all of Mr. Assange’s arguments regarding political motivation, political offense, fair trial, and freedom of speech.”

Press-freedom advocates have warned that prosecuting Assange under the Espionage Act for disclosing what was the biggest leak of classified information in U.S. history would criminalize what has long been a standard journalistic practice.

“We welcome the fact that Julian Assange will not be sent to the USA, but this does not absolve the UK from having engaged in this politically-motivated process at the behest of the USA and putting media freedom and freedom of expression on trial,” Amnesty International wrote in a statement.

But U.S. prosecutors claim that Assange’s actions went beyond journalism, such as conspiring with Manning and other sources to hack into private databases.

“This court trusts that upon extradition, a US court will properly consider Mr. Assange’s right to free speech and determine any constitutional challenges to their equivalent legislation,” the judge wrote.

For Judge Baraitser, Assange’s alleged journalist-source relationship with Manning “went beyond the mere encouragement of a whistle-blower.”

Citing arguments by Assistant U.S. Attorney Gordon Kromberg, the judge found it legitimate to attempt to punish the allegedly knowing disclosure of the identities of U.S. informants whose lives were uprooted by the leaks.

“As Mr. Kromberg points out, well over one hundred people were placed at risk from the disclosures and approximately fifty people sought and received assistance from the U.S.,” the judgment states. “For some, the U.S. assessed that it was necessary and advisable for them to flee their home countries and that they, their spouses and their families were assisted in moving to the U.S. or to safe third countries. Some of the harm suffered was quantifiable, by reference to their loss of employment or their assets being frozen by the regimes from which they fled, and other harm was less easy to quantify.”

At Manning’s court-martial, a U.S. general conceded that none of the leaks led to any deaths, but those identified had to be shuttled to safety.

When prosecutors first unsealed charges against Assange in 2019, the first public indictment’s computer intrusion charge focused on revelations from Manning’s trial that the two allegedly discussed cracking a password to obtain anonymous access to the Net Centric Diplomacy database, which held the hundreds of thousands of State Department cables sent to WikiLeaks.

At the time of her leaks, Manning had lawful access to that database, but prosecutors said at her court-martial that she and Assange sought illegal access to evade detection. That alleged conspiracy, disclosed during Manning’s trial, is part of Assange’s indictment.

Judge Baraitser found that would be for the U.S. judiciary to decide.

“Whether or not it was possible for Ms. Manning to crack the passcode, and whether she was aware of the security issues, are in my judgment matters for a trial,” the U.K. judgement states.

Shortly after her arrest, Manning was found to have been suicidal and a noose was found in her prison cell, leading to highly restrictive pretrial conditions that a military judge found to have been excessive. Assange cited Manning’s attempted suicide, according to the WikiLeaks founder’s psychiatrist.

This past June, U.S. prosecutors widened the scope of their computer-intrusion charges, saying that Assange also asked a teenager to steal audio recordings of phone conversations between high-ranking officials of a NATO country, including a member of its parliament.

The superseding indictment also charges that Assange played a hands-on role in connection with hacks by collectives Anonymous, Gnosis, AntiSec, and LulzSec. Their targets included a cyber security company, two hundred U.S. and state government email accounts, the private intelligence firm Stratfor and multiple law enforcement associations.

Jeremy Hammond, one of the the key figures behind the Stratfor intrusion who also broke into Boston and Alabama police databases, was sentenced to a decade imprisonment in 2013. WikiLeaks published his disclosures under the name “Global Intelligence Files.”

Assange’s charges larges focus on conduct spanning back a decade.

Former President Barack Obama’s administration did not unveil any prosecution of Assange by the end of his second term. A Washington Post report from the sunset of Obama’s presidency suggested that some in his Justice Department expressed First Amendment concerns they described as a “New York Times problem,” meaning that legal theories deployed against Assange now could be used against the paper of record later.

The Trump administration backpedaled, leading Assange’s defense team to argue there was a political vendetta.

But Baraitser noted that Trump is hardly antagonistic to Assange, whose publication of Democratic National Committee emails was exploited by the Russian government in its efforts to interfere with the 2016 presidential election.

“First, there is little or no evidence to indicate hostility by President Trump towards Mr. Assange or Wikileaks,” the judge noted. “His reported comments suggest that he was well-disposed towards them both.”

When former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton appeared certain to win the 2016 election, Assange reportedly told Trump’s son that he should refuse to concede the race. Though he is not currently charged with any conduct related to that election, Assange’s name came up repeatedly in the Mueller investigation and the prosecution of Roger Stone, whom Trump since pardoned.

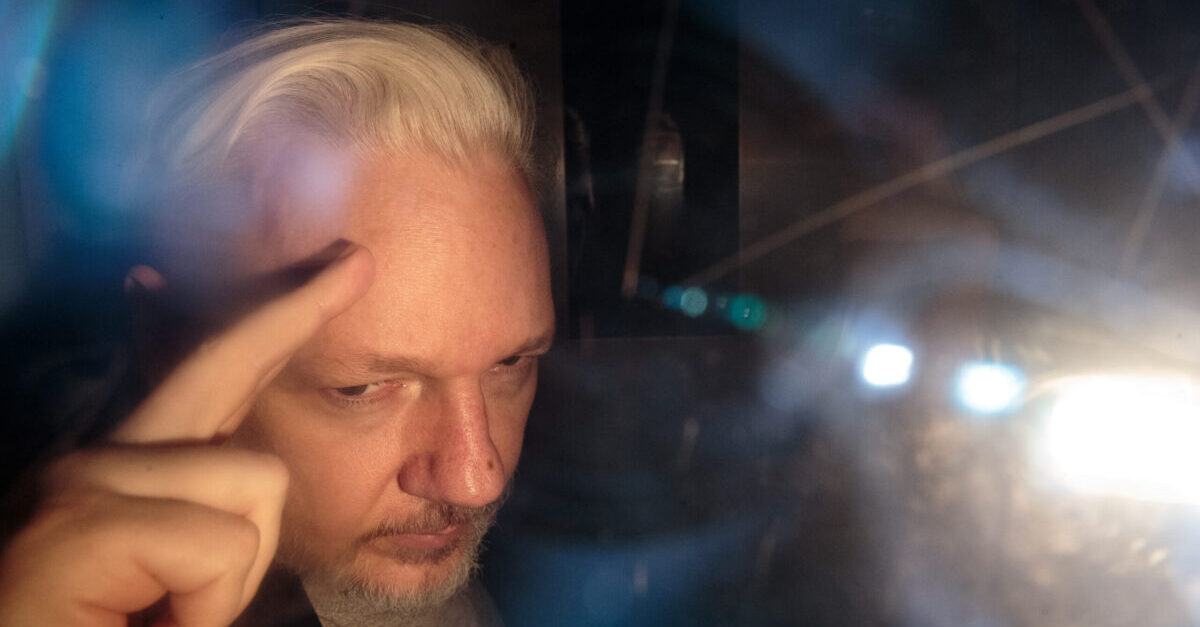

[Image via Jack Taylor/Getty Images]