The Supreme Court’s ruling Thursday night is causing religious freedom advocates’ heads to spin. The Court ruled that Texas can’t discriminate against death-row Buddhists – but simultaneously proved that the Court can discriminate against death-row Muslims. Okay, “discriminate” may be an overly-harsh way to describe SCOTUS’ inconsistency, but something seriously stinks here.

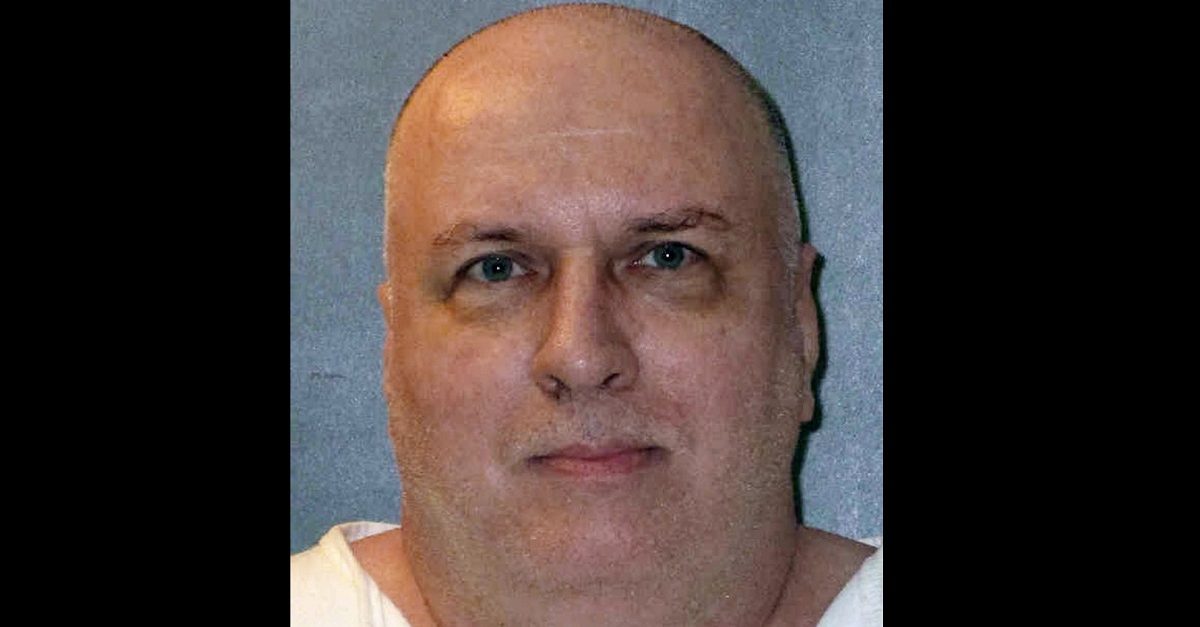

Patrick Murphy is a member of the “Texas 7” gang of escaped prisoners who was sentenced to death for killing 29-year-old Irving Police Officer Aubrey Hawkins. Murphy has been in prison since 2003, awaiting death by lethal injection.

Murphy’s sentence was to be carried out Thursday night, but was granted a last-minute stay by the Supreme Court when it ruled against the State of Texas for its policy on spiritual advisors. Murphy, a Buddhist for over a decade, requested that a Buddhist priest accompany him in the execution chamber; Texas refused, on grounds that it only allows Christian and Muslim spiritual advisors to enter the chamber. SCOTUS voted 7-2 against Texas’ policy. No opinion, only a short statement, accompanied the Court’s order:

The State may not carry out Murphy’s execution pending the timely filing and disposition of a petition for a writ of certiorari unless the State permits Murphy’s Buddhist spiritual advisor or another Buddhist reverend of the State’s choosing to accompany Murphy in the execution chamber during the execution.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, siding with the Court’s majority, called out Texas for what it was doing – discriminating:

In this case, the relevant Texas policy allows a Christian or Muslim inmate to have a state-employed Christian or Muslim religious adviser present either in the execution room or in the adjacent viewing room. But inmates of other religious denominations—for example, Buddhist inmates such as Murphy—who want their religious adviser to be present can have the religious adviser present only in the viewing room and not in the execution room itself for their executions. In my view, the Constitution prohibits such denominational discrimination.

All this seems like justice done, even if Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch would have ruled against Murphy. The only problem is that the ruling is wildly at odds with what SCOTUS did just last month.

In February, the Court heard a last-minute appeal from Alabama death row inmate Domineque Ray; Ray, a Muslim, had requested to have his imam by his side during his execution. Alabama refused, insisting that only religious figures of its choosing would be permitted. The state’s Protestant chaplain was allowed, but Ray’s Muslim imam was not. Ray’s appeal made its way up to the high bench, where the Court ruled against the condemned man. Ray was executed by lethal injection without his imam by his side.

In the Ray case, Justice Elena Kagan, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor dissented, calling the majority’s decision “profoundly wrong.”

While it’s gratifying to see SCOTUS issue a far more logical decision in Murphy’s case, taking the two together is deeply troubling in its own right. What is there to explain conflicting outcomes in two nearly-identical cases separated by just a few weeks? Unfortunately, not much.

The majority siding against Texas in Murphy’s appeal issued no opinion, leaving us to speculate that the basis for the ruling was one supported by common sense: giving preferential treatment to Christians and Muslims while closing out Buddhists is textbook religious discrimination. By contrast, the Thomas-led (5 to 4) majority ruling against Domineque Ray ignored what the 11th Circuit called a “powerful” First Amendment claim, finding (though no factually-supportive evidence was introduced) that Ray’s request for the imam had been made too late.

Whether the incongruence of the Ray and Murphy outcomes is more directly attributable to latent Islamophobia or misplaced deference to state-sovereignty over executions is debatable. What is not, though, are the facts. The majority of the U.S. Supreme Court is apparently willing to put forth opposite outcomes when cases differ only in that one has a thin and unsupported state claim of untimeliness, and that the other involves a Buddhist as opposed to a Muslim.

Follow Elura on Twitter @elurananos

[Image via Texas Department of Criminal Justice]

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.