Phil Houston is CEO of QVerity, a training and consulting company specializing in detecting deception by employing a model he developed while at the Central Intelligence Agency. He used this model to analyze last night’s Republican debate. His colleague Don Tennant contributed to this report.

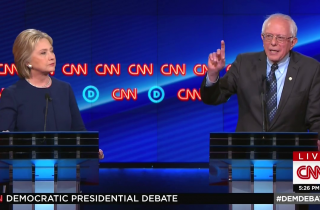

Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders couldn’t help themselves toward the end of Sunday night’s Democratic debate in Flint, Mich. They had to draw the electorate’s attention to the glaring difference between the decorum and the focus on the issues that had been on display throughout the evening, and the buffoonish attack fest that characterized Thursday night’s Republican debate.

“I just want to make one point,” Clinton said. “We have our differences, and we get into vigorous debate about issues. But compare the substance of this debate with what you saw on the Republican stage last week,” she gloated. Then it was Sanders’s turn.

“We are, if [I am] elected president, going to invest a lot of money into mental health,” he said. “And when you watch these Republican debates, you know why we need to address mental health.”

Clinton’s condescension and Sanders’s rather thoughtless, boorish mental health remark aside, it was easy for many viewers to be caught up in the moment and to elevate the Democratic candidates above their Republican rivals. But if rectitude of conduct is the gauge of who should be elevated over whom, don’t be fooled. The deception Clinton and Sanders exhibited was every bit as egregious as what we saw on that Republican stage Thursday night.

There’s nothing particularly surprising about that, when you consider that politicians strive to be all things to all people, and it’s very difficult to be perceived as such without engaging in deception. But what we found enlightening was the difference between how the Republicans and Democrats approached their deception. The common denominator was a repeated failure to answer the policy-related questions they were asked, and the reason for that is simple: To go on record with a definitive policy would almost certainly alienate some significant portion of the electorate. That necessarily creates a bit of a hiccup in the quest to be all things to all people.

To appreciate the difference in approach, consider that the evasion behavior in the form of failure to answer the questions during the Republican debate was routinely accompanied by attack behavior to help successfully pull off the evasion. The attacks may be ugly, but they’re remarkably effective in distracting voters, and in lending credibility to the notion that the last man standing, after all the ugliness, is at least successful in accomplishing something. That’s an attractive trait to an electorate that is starved for action in resolving the issues they care about.

During the Democratic debate, on the other hand, failure to answer the question was routinely accompanied by persuasion behavior as a means of succeeding in the evasion. And an intriguing dimension of that is the difference between how Clinton and Sanders pursued their persuasion.

More often than not, Sanders would avoid answering the question directly by referring to his track record, in an effort to convince the electorate to conclude that based on a particular pattern of past activity, he would be successful in addressing the matter at hand in the future.

For example, when CNN’s Anderson Cooper asked him where fixing the nation’s broken school systems falls on his list of things to do, instead of responding directly to the question, Sanders put the spotlight on his track record in advocating tax reform.

“When you ask me about my priorities, my priorities are that we’re not going to give tax breaks to the wealthy,” he said. “We’re going to ask them to start paying their fair share of taxes so we can raise the money to make sure that every child in this country—in Detroit, in Vermont—gets the quality education that he or she deserves.”

It’s worth mentioning that the irony inherent in Sanders’s strategy of relying on his track record as a persuasion mechanism is that so much of what he has set out to accomplish over the years has been unsuccessful, yet he expects the electorate to make that leap of faith. Of course, that’s hardly far fetched—his followers have already made that leap.

In Clinton’s case, the persuasion behavior routinely took the form of identifying with the problem that surfaced in the question, and conveying the perception that she knows more about the problem than the questioner does.

For example, on the issue of what actions need to be taken in the aftermath of revelations that have emerged with regard to Flint’s contaminated water supply, Clinton deftly suggested that she has a broader, more informed perspective by expanding the issue beyond Flint.

“This is not the only place where this kind of action is needed,” she said. “We have a lot of communities right now in our country where the levels of toxins in the water, including lead, are way above what anybody should tolerate.”

The apparent intent here is to convey the message, “If I know more about the problem than you do, I must have the strategy and means to fix it.” The inherent flaw in that logic is simply that knowing more about the problem is not a strategy for success in solving it.

Another example arose when CNN’s Don Lemon asked Clinton what racial blind spots she has. Rather than respond to the question, Clinton said she wanted to go back and respond to a question an audience member had asked Sanders, about what experiences he’s had that have enabled him to understand the values of other cultures.

“I think the most important thing to happen to me was a combination of my church, and my youth minister, when I was a teenager, insisting that we go into inner city Chicago, because I lived in a suburb, and have exchanges with kids and black and Hispanic churches,” she said. “It was also important for me to be a babysitter for the children of migrant workers, and to learn more about their lives, and to go hear Dr. King speak in Chicago when I was about 14 years old.”

The message was that she was so knowledgeable about minority communities, that a question about her racial blind spots was moot.

And then there was the particularly fascinating response Clinton gave to a question from Anderson Cooper during a discussion raised by an audience member on the topic of fracking. Cooper noted that Sanders often refers to a Clinton fundraiser in January that was hosted by executives from a firm that has invested significantly in domestic fracking. He asked Clinton if she had any comment on that.

“I don’t have any comment. I don’t know that, I don’t believe that there’s any reason to be concerned about it,” she said. And then the kicker, referring to Sanders’s fundraising: “I admire what Senator Sanders has accomplished in his campaign.”

That Clinton failed to answer the question in any meaningful, informative way, which she certainly would have been inclined to do if it had been in her best interest, was consistent with her behavior throughout the debate. What’s distinctive in this case is the length she went to—praising the one person who’s standing in the way of securing the nomination of her party—in order to avoid answering the question. The takeaway here is that if praising Sanders was more appealing to her than responding to the question, the issue surfaced by that question likely involves information that Clinton is very eager to conceal.

Clinton’s persuasion approach, to present herself as knowing more, was accompanied by the repeated refrain that we all need to do more. Absent a definitive policy or strategy, that approach is clearly nothing more than an effort to pull the wool over the eyes of an electorate that’s starved for action. Yet the fact that she is so effective in that regard suggests that her action-oriented approach will likely resonate with voters on a much broader scale than the track record approach taken by Sanders. If Clinton won Sunday night’s debate, that resonance was almost certainly a significant contributing factor and may ultimately gain her the nod over Sanders for the Democratic nomination.