Environmentalists scored a significant victory in the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday with help from some unusual suspects.

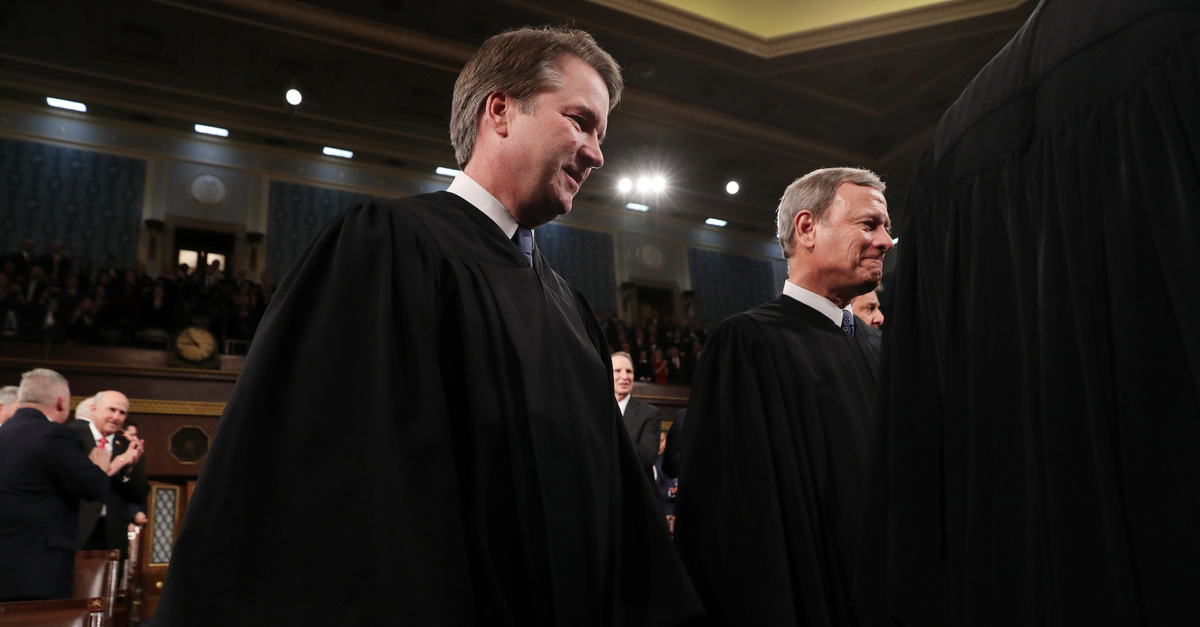

In a 6-3 opinion authored by Justice Stephen Breyer, two of the court’s conservatives–Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh–joined with the four-member liberal minority in order to strengthen a key provision of the Clean Water Act (CWA) of 1972.

Stylized as County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund, the case stems from a lawsuit filed by “several environmental groups” in 2012 which alleged that Maui’s use of a wastewater reclamation facility ran afoul of the CWA by pumping roughly four million gallons of treated wastewater into the Pacific Ocean every day without a permit.

The permitting requirement is considered the heart and soul of the CWA’s overall regulatory effectiveness.

Under the CWA, a permit is required for the “discharge of any pollutant” into U.S. waters–which is defined as “any addition of any pollutant to navigable waters from any point source [or] any addition of any pollutant to the waters of the contiguous zone or the ocean from any point source other than a vessel or other floating craft.”

The term “pollutant” is defined broadly by the nation’s longstanding environmental statute and also specifically includes “solid” and “municipal…waste discharged into water.”

The plaintiff environmental groups claimed that Maui’s disposal of wastewater via injection wells, which are “essentially long pipes,” necessitated a permit under CWA § 404.

“Maui’s wastewater reclamation facility collects sewage from the surrounding area, partially treats it, and each day pumps around 4 million gallons of treated water into the ground through four wells,” the majority opinion notes. “This effluent the travels about a half mile through groundwater, to the Pacific Ocean.”

Kavanaugh’s concurrence clearly sums up the basic issue:

The question in this case is whether the County of Maui needs a permit for its Lahaina Wastewater Reclamation Facility. No one disputes that pollutants originated at Maui’s wastewater facility (a point source), and no one disputes that the pollutants ended up in the Pacific Ocean (a navigable water). Maui contends, however, that it does not need a permit. Maui says that the pollutants did not come “from” the Lahaina facility because the pollutants traveled through groundwater before reaching the ocean.

Leaning heavily into a prior opinion by late justice Antonin Scalia, Kavanaugh tries his level best to convince his ideological peers:

Justice Scalia reasoned that the Clean Water Act does not merely “forbid the ‘addition of any pollutant directly to navigable waters from any point source,’ but rather the ‘addition of any pollutant to navigable waters.’ Thus, from the time of the CWA’s enactment, lower courts have held that the discharge into intermittent channels of any pollutant that naturally washes downstream likely violates [the CWA’s effluent limitations], even if the pollutants discharged from a point source do not emit ‘directly into’ covered waters, but pass ‘through conveyances’ in between.”

Without any such reliance on Scalia, Breyer’s majority opinion dismisses Maui’s concerns and the dissent’s argument that the wastewater doesn’t qualify as a “discharge” under the statute because the pollutants are not directly released from a point source into navigable waters.

“We hold that the statute requires a permit when there is a direct discharge from a point source into navigable waters or when there is the functional equivalent of a direct discharge,” the opinion notes with emphasis in the original. “We think this phrase best captures, in broad terms, those circumstances in which Congress intended to require a federal permit.”

The italicized phrase, however, is nowhere to be found in the text of the statute but, rather, comes from a rule developed by the Ninth Circuit.

Conservative Justice Samuel Alito heaped scorn on the majority opinion for their use of the phrase.

“If the Court is going to devise its own legal rules, instead of interpreting those enacted by Congress, it might at least adopt rules that can be applied with a modicum of consistency,” the conservative justice complains. “Here, however, the Court makes up a rule that provides no clear guidance and invites arbitrary and inconsistent application.”

“This is not a plausible interpretation of the statutory text and, to make matters worse, the Court’s test has no clear meaning,” Alito goes on. “Just what is the ‘functional equivalent’ of a ‘direct discharge’? The Court provides no real answer.”

Alito’s dissent also slams the unusual pairing of justices in the majority for their efforts “to find a middle way.”

The Ninth Circuit previously ruled in favor of the plaintiffs as well–but its decision was vacated for using a “more absolute position” which was likened to the government’s position.

Essentially, Thursday’s ruling in County of Maui is an attempt to thread the needle between the heavily plaintiff- and environmentalist-friendly theory used by the lower court and the polluter-friendly positions advanced by the government.

[image via Leah Millis-Pool/Getty Images]