President Donald Trump on Black Friday tweeted to suggest that Joe Biden must satisfactorily prove that he won the 2020 presidential election before occupying the White House as president. That is not an accurate representation of the legal reality of the president or his allies’ uphill battles in court, which he and they successively keep losing. It is also a sign that they will likely continue to lose.

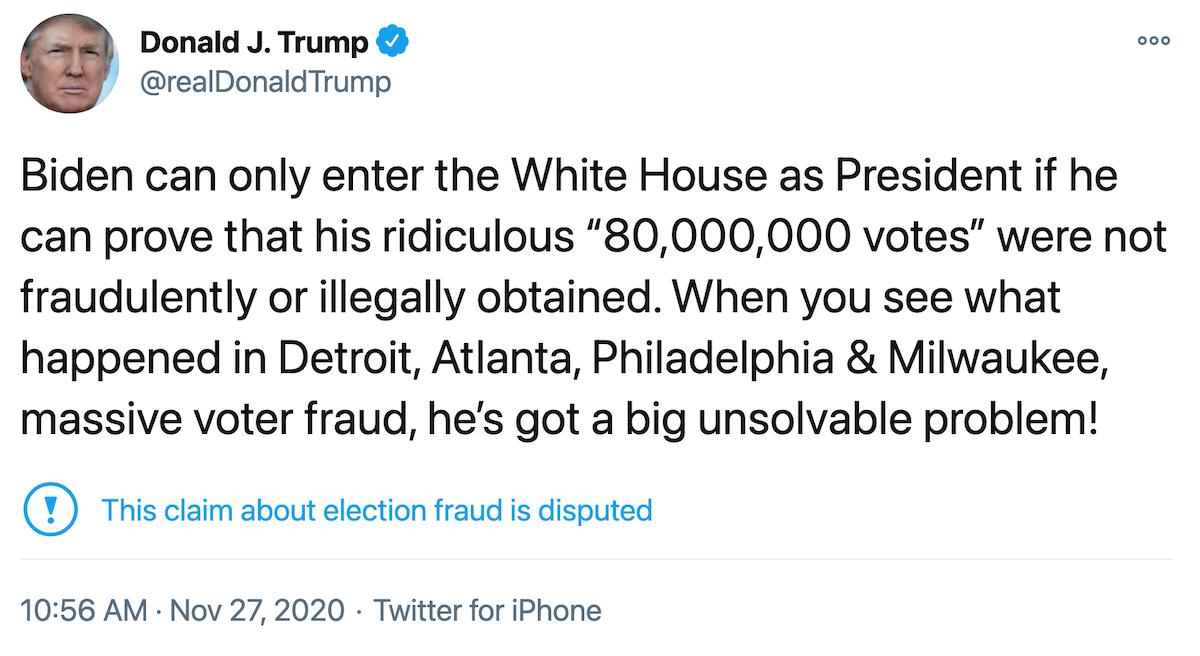

“Biden can only enter the White House as President if he can prove that his ridiculous ‘80,000,000 votes’ were not fraudulently or illegally obtained,” Trump said on Twitter. “When you see what happened in Detroit, Atlanta, Philadelphia & Milwaukee, massive voter fraud, he’s got a big unsolvable problem!”

The post was flagged with Twitter’s now-commonplace warning about the factual legitimacy of statements made by the president.

Experts were swift to note that the president’s tweet reeked of the sort of burden shifting that is generally not permissible in a court of law (absent some specific mechanism for it to occur).

Sir, that’s not how this works. The burden of proof was on you and your lawyers. They failed because they do not have evidence of fraud. You can lie to us, but you cannot lie to the courts.https://t.co/UAw2lqzgUG

— Jennifer Taub (@jentaub) November 27, 2020

Indeed, the core concept is rather elementary:

Dear law students, this is called “burden shifting.” Don’t do this. You will lose.

— feminist next door (@emrazz) November 27, 2020

Nah, the burden of proof lies with the accuser. President-elect Biden will enter the White House as President on January 20, 2021.

— Joel Dolphin (@DJdolph) November 27, 2020

Let’s hit the books to prove this point of unexpectedly sudden contention.

As one law school civil procedure textbook notes, “the party with the burden of proof, usually the plaintiff, must have a sufficiency of evidence as to each element of at least one cause of action to permit a reasonable fact finder to find that each element is true.” That’s the burden of production. The burden of persuasion measures, from the perspective of a judge or of a jury, whether a litigant has presented sufficient evidence to actually convince a jury (or a judge at a bench trial) that his facts are believable and that the scales of justice should tip in his favor.

“Ordinarily, the burden of proof is in the first instance with the party who initiates the action or proceeding, that is, the plaintiff,” lawyer Martin Weinstein once wrote. “In other words a plaintiff, by asserting facts which, if proved, would establish liability on the part of the defendant, has the burden of proving these facts.”

In other words, Trump, by asserting Biden “fraudulently or illegally obtained” the election, bears the burden of proving that the election was indeed as described; and that is something not even his own lawyers have sought to or been able to prove (example 1, example 2, example 3, example 4). Trump’s people have neither proven it nor have tried; legally, Biden certainly does not have to prove it. In normal litigation, the only burden borne by an adverse party — generally speaking — is to assert affirmative defenses or to present counterclaims or crossclaims.

To be clear, however, so-called “burden shifting” is allowed in some situations, such as Title VII employment discrimination lawsuits.There, the law explicitly demands it: when a plaintiff applicant puts forth certain evidence of employer discrimination, the defendant employer must rebut it with nondiscriminatory reasons for certain employment actions. Even in this context, however, the plaintiff who files the case carries the primary burden. Burden-shifting was also part of a recent Supreme Court analysis involving antitrust regulation as applied to the markets for credit cards. Similarly, Supreme Court fashioned a rule analogous to burden shifting in the realm of litigation filed by prison inmates. Though the law requires prisoners to exhaust internal administrative remedies before suing over their conditions or treatment behind bars, it is the job of prison officials to raise the plaintiff’s failure to exhaust administrative remedies as an affirmative defense. It is not the plaintiff’s job to prove he already exhausted all his remedies before filing a lawsuit. That’s sort of like burden shifting, but not quite the same thing.

Finally, something similar to burden shifting part of the process by which summary judgment is conducted in civil trials: if a plaintiff satisfies the burden of production, a defendant then bears the burden of proving a genuine factual dispute worthy of jury consideration. If the facts are not in dispute, then a judge makes a decision on who wins and who does not.

In federal courts, summary judgment under Rule 56 is a process which occurs only after a plaintiff passes the preliminary gatehouse of civil litigation: Rule 12(b)(6). That rule addresses whether a plaintiff has failed to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. In litigation involving the 2020 election, Trump and his allies are either withdrawing their own complaints or are failing the much earlier Rule 12(b)(6) pleading standard (or its functional equivalent in state court). In other words, they are failing to get into court in the first place because they don’t have enough evidence to back themselves up. To wit, as the Third Circuit ruled Friday, a district court properly refused to to allow amendments to an official Trump campaign lawsuit against various Pennsylvania officials because even the “Second Amended Complaint would not survive a motion to dismiss.” Therefore, “the District Court properly denied leave to file it.”

Trump’s Friday tweet attempts to shift the burden to Biden to prove the election was not fraudulent. It is at least some proof that Trump has nothing compelling to present in court. Rule 301 of the Federal Rules of Evidence further summarizes why. “In a civil case, unless a federal statute or these rules provide otherwise, the party against whom a presumption is directed has the burden of producing evidence to rebut the presumption,” the rule reads, but here’s the clincher: “this rule does not shift the burden of persuasion, which remains on the party who had it originally.” The rule states clearly who shoulders the burden of persuasion. It is not the person accused. By suggesting Biden should carry that burden, Trump suggests his lawyers or their allies cannot carry it on their own.

[Photos by ANGELA WEISS and MANDEL NGAN / AFP via Getty Images]