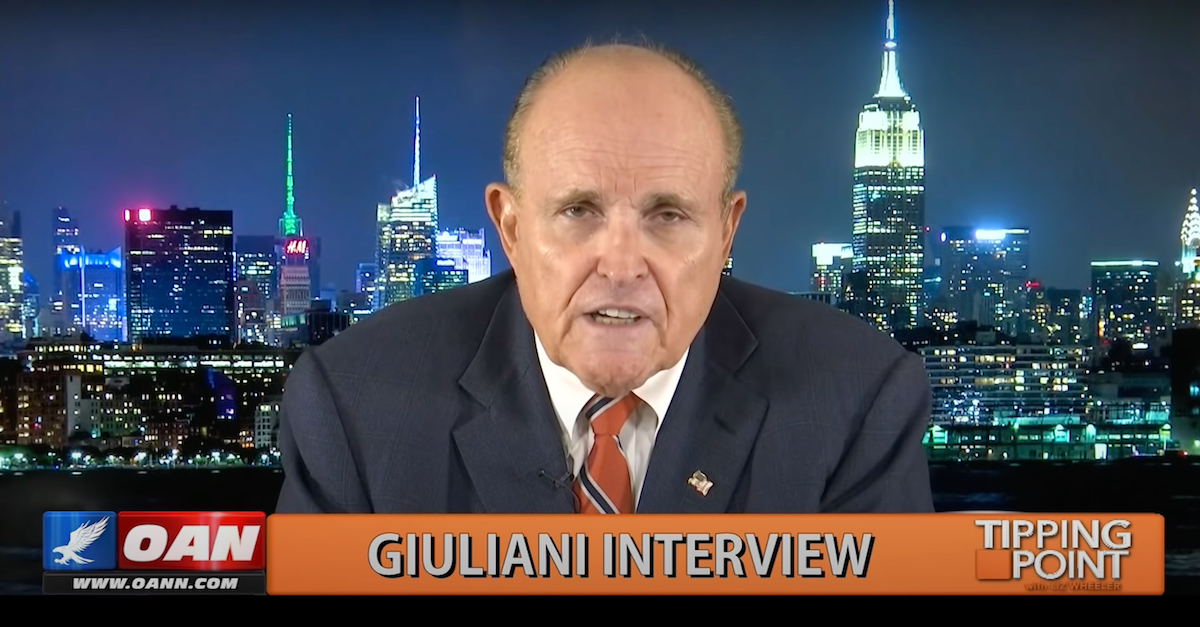

Rudy Giuliani.

Former Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani on Friday filed response papers to a defamation lawsuit launched against him by two 2020 Georgia election workers. One of the responses contains a stark and curious admission to what the defense calls “merely one element” of a defamation claim, but Giuliani’s lawyer otherwise vows to fight the overall allegations of liability and denies that Giuliani “lied” about the plaintiffs who are suing him.

The original matter, filed by plaintiffs Ruby Freeman and Wandrea “Shaye” Moss just before Christmas in 2021, alleges that a collection of defendants — Giuliani among them — “bear responsibility for the partisan character assassination” that resulted after the 2020 presidential election. Freeman was a “temporary election worker,” while Moss “supervised Fulton County’s absentee ballot operation during the 2020 general election,” the lawsuit says.

The case, stylized as Freeman v. Herring Networks, Inc., names Giuliani as an individual defendant. Herring Networks operates the One America News (OAN) Network. Also named as defendants are correspondent Chanel Rion, network founder Robert Herring, and network president Charles Herring.

The Giuliani response is a typical tit-for-tat, line-by-line rebuttal to the claims dispatched by the plaintiffs last year.

“The conduct of free and fair elections in the United States relies upon the service of nonpartisan election workers,” the original lawsuit alleged. “For most of American history, these ordinary citizens have received thanks for their efforts, even from those candidates who have come up short. In the 2020 federal election, however, that venerable tradition was decimated by anti-democratic actors desperate for scapegoats whom they could blame for election results that they refused to accept.”

Giuliani responded to that paragraph as follows:

This paragraph contains rhetorical argument containing opinions to which no response is required. However, to the extent the paragraph makes factual assertions regarding election workers being essential to democracy, Giuliani admits this is true and denies the remainder of the paragraph to the extent it makes any factual assertions.

Elsewhere, Giuliani admitted the basic factual assertion that the “Plaintiffs were election workers in Georgia during the 2020 Election,” but he refused to admit that the plaintiffs were “among those scapegoats” in myriad allegations of election malfeasance. He also refused to admit that the plaintiffs “share a patriotic commitment to a free and fair democratic process.”

The bulk of Giuliani’s 21-page response contains copious and perfunctory denials of overall wrongdoing, but his response to paragraph 23 of the plaintiff’s lawsuit stands out. Here’s the original accusation by the plaintiffs (with emphasis added):

23. Defendant Rudolph W. Giuliani is a former politician and government official who has become a podcast and radio show host, a media figure, and (at times) the personal attorney to Donald Trump. He is domiciled in New York but has engaged in a persistent course of conduct in the District relating to the statements at issue, and on information and belief, made certain of the defamatory statements described below from Washington, D.C.

Here’s the terse and punctual response:

23. Admitted.

That one-word response did not carefully parse out or even attempt to segregate the words “defamatory statements” from the rest of the allegations in the original.

Austin, Texas attorney Joseph D. Sibley IV, who is representing Giuliani, replied as follows via email when asked by Law&Crime to explain the paragraph 23 admission:

In defamation law, there is a difference between a statement carrying a defamatory meaning (tending to cast a person in a negative light), and being liable for the tort of defamation, with all of its elements/nuances. Obviously, we are taking the position that Mr. Giuliani is not liable for the tort of defamation (or any other causes of action) in this case. However, we cannot and will not take the position that his statements that carry accusations of election fraud do not carry defamatory meaning. That would not be a good faith position. But defamatory meaning is merely one element of a defamation claim, and we intend to demonstrate that Plaintiffs cannot meet several of those other elements (in addition to overcoming our affirmative defenses). Beyond that, I cannot comment.

The question of whether a statement is capable of carrying a “defamatory meaning” is generally a question of law — that is, one for a court to decide at the summary judgment stage of a proceeding before a jury is seated, according to a number of cases. One such case explains as follows (we’ve omitted the many legal citations):

Procedurally, it is the function of the court, in the first instance, to determine whether the communication complained of is capable of a defamatory meaning. If the court determines that the statement is capable of a defamatory meaning, it is for the jury to determine whether it was so understood by the recipient.

Another case expounds as follows (again, citations omitted):

Whether a publication is capable of a defamatory meaning is initially a question for the court. But when a publication is of ambiguous or doubtful import, the jury must determine its meaning.

And another:

If, at the summary judgment stage, the court determines that the publication is capable of bearing a defamatory meaning, a jury must determine whether such meaning was attributed in fact.

[ . . . ]

Generally, a publication may convey a defamatory meaning if it “tends to lower [the] plaintiff in the estimation of a substantial, respectable group, though they are a minority of the total community or plaintiff’s associates.”

The analysis can get tricky, as that last case pointed out, because “defamatory inference[s]” can still be drawn from “materially true facts.” And, if that happens, plaintiffs can still lose, the case law points out. Here’s the relevant passage of the Washington, D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals case referenced several times herein:

[I]f a communication, viewed in its entire context, merely conveys materially true facts from which a defamatory inference can reasonably be drawn, the libel is not established. But if the communication, by the particular manner or language in which the true facts are conveyed, supplies additional, affirmative evidence suggesting that the defendant intends or endorses the defamatory inference, the communication will be deemed capable of bearing that meaning.

As a whole, Giuliani’s attorney appear willing to concede one sole step in the analysis but still wishes to challenge the other steps. The additional steps or elements, according to the first case cited above (which itself cites the original 1938 Restatement of Torts), might include the following:

In an action for defamation, the plaintiff has the burden of proving, when the issue is properly raised: (a) The defamatory character of the communication; (b) Its publication by the defendant; (c) Its application to the plaintiff; (d) The recipient’s understanding of its defamatory meaning; (e) The recipient’s understanding of it as intended to be applied to the plaintiff; (f) Special harm resulting to the plaintiff from its publication; (g) Abuse of a conditionally privileged occasion.

Accordingly, the reply document naturally asserts a number of affirmative defenses, including the First Amendment, a possible statute of limitations, the single publication rule, litigation privilege/attorney immunity, a legislative proceeding privilege and/or official proceeding privilege, that “some and/or all of Giuliani’s statements complained of are substantially true,” and that any damages suffered “were not caused by Giuliani” but rather by “intervening and/or superseding causes.”

Elsewhere in the reply document, Giuliani vociferously and persistently denied multiple “factual assertions” by the plaintiffs that he “lied” when he spoke about the 2020 election. In yet another section of the reply, Giuliani denied that he promulgated “lies about Plaintiffs” and denied that his alleged “lies were outlandish.”

Indeed, most of the reply contains this response to the assertions of wrongdoing: “This paragraph contains legal contentions to which no response is required.” Or, it says Giuliani “denies . . . the paragraph to the extent it makes any factual assertions.”

Giuliani also responded to the following plaintiff paragraph which purported to recap his core claims with regard to the plaintiffs:

At the hearing, a lawyer assisting the Trump campaign published snippets of surveillance video of the absentee and military vote count at State Farm Arena. This edited footage from the surveillance video will hereafter be called the “Trump Edited Video.” While the Trump Edited Video played, the campaign surrogate claimed that Republican observers had been asked to leave the arena in contravention of Georgia law and that, once they were gone, Plaintiffs and other election workers produced and counted 18,000 hidden, fraudulent ballots—more than the margin of victory in the presidential race. The surrogate referred to “suitcases of ballots [stored] under a table, under a tablecloth;” identified the election workers in the room as “the lady in purple,” “two women in yellow,” and “the lady with the blond braids also, who told everyone to leave;” and stated that “one of them had the name Ruby across her shirt somewhere.”

Here’s the Giuliani response to those allegations:

Giuliani admits that quotations appear in the cited references, Giuliani admits that a video existed and exists and was published during the event in question, however, he denies the allegations that the video was manipulated to create a false impression.

In a reply to paragraph 131 of the original lawsuit, Giuliani “[a]dmitted” the original allegation that he “helped the Trump Campaign formulate its legal strategy in the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election, participated directly in some of its lawsuits, represented the Trump Campaign in hearings before multiple state legislatures, hosted press conferences, and made media appearances—including on OAN.” However, he “denied” that he undertook those efforts “as to President Trump” personally. In other words, he asserts that he was assisting the campaign as an organization but not Trump as an individual.

In a reply to paragraph 134, which alleged in part that “Giuliani led the Trump Campaign’s ‘war room’ . . . at the Willard Hotel,” Giuliani “admits to being engaged at activities on behalf of the Trump Campaign at the Willard Hotel but denies the truth of the remaining allegations.”

As to paragraph 135, Giuliani admitted to speaking on the Ellipse on Jan. 6, 2021 but denied the assertion that he promulgated “lies about Plaintiffs” while so doing.

“Giuliani denies all allegations in the prayer for relief,” the document states near its conclusion. Giuliani also denies that the plaintiffs are private figures for the purposes of defamation law.

“Defendant prays that Plaintiffs take nothing, that Defendant be awarded his costs, and for all other relief to which Defendant shows himself entitled,” the filing concludes.

Read the original document and Giuliani’s response below:

[Image via screengrab from OAN/YouTube.]

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]