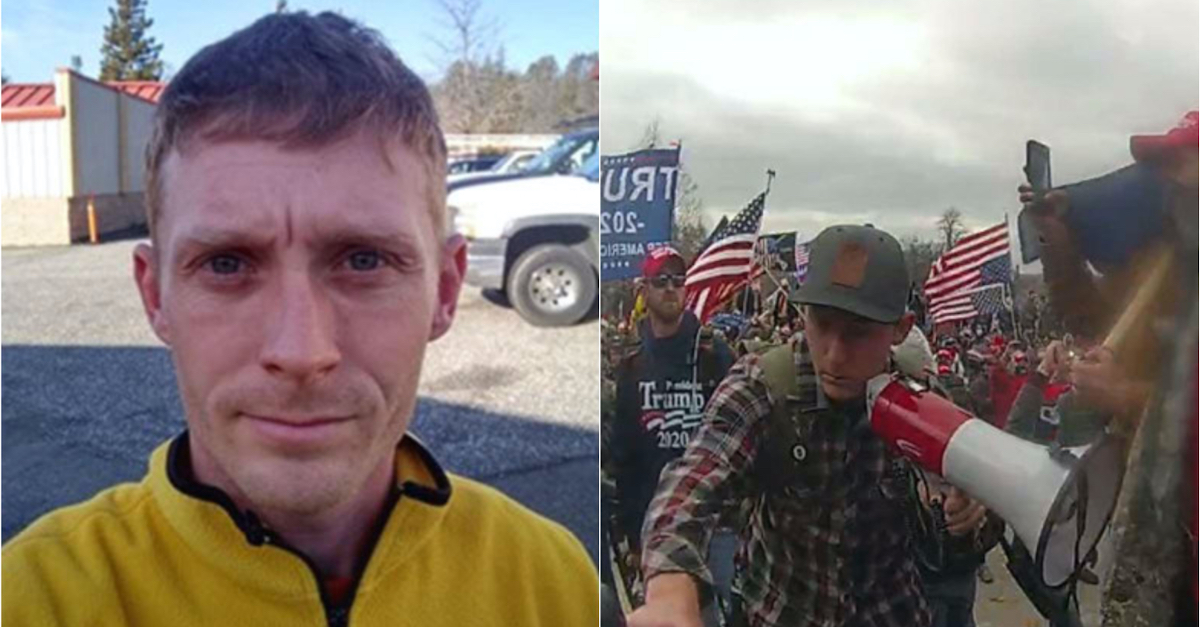

Sean McHugh (courtesy FBI)

A seventh judge has rejected a Jan. 6 defendant’s attempt to have a federal obstruction charge dismissed, further solidifying a growing consensus on the bench that prosecutors can pursue the felony charge against Jan. 6 defendants.

U.S. District Judge John D. Bates issued his ruling Tuesday on Sean Michael McHugh’s motion to dismiss, denying the motion in its entirety.

McHugh faces 10 charges, including eight felonies, in connection with the Jan. 6 Capitol riots, when hundreds of Donald Trump supporters overran police and breached the building in an attempt to stop Congress from certifying Joe Biden’s win in the 2020 presidential election.

McHugh has previously been convicted of statutory rape.

Prosecutors say that on Jan. 6, McHugh sprayed police with bear spray, fought with a police officer over a metal barricade, and helped fellow rioters push a large metal sign into officers. He faces felony charges of assaulting, resisting, or impeding federal officers, at points with a dangerous weapon. He is also charged with obstruction of justice, a felony, for impeding the certification of the presidential election results.

That last charge, which technically carries a potential 20-year prison sentence, has been the subject of multiple motions to dismiss before an array of judges in the D.C. district, all of which have been denied.

“With the exception of McHugh’s very last argument regarding the phrase ‘temporarily visiting,’ every one of these contentions has been heard and rejected by at least one judge in this District in the last several months,” Bates notes in his ruling.

Bates, a George W. Bush appointee, is now the seventh judge to reject a motion to dismiss the obstruction charge. U.S. District Judges Dabney Friedrich and Timothy Kelly—both Trump appointees—along with Barack Obama appointees James Boasberg, Randolph Moss, and Amit Mehta have all issued written rulings that rejected attempts from Jan. 6 defendants trying to get the obstruction charged dismissed.

Chief U.S. District Judge Beryl Howell, also an Obama appointee, issued an oral ruling in January similarly aligning with her colleagues’ categorical denials of the motions to dismiss.

Bates: McHugh’s “Official Proceeding” Argument “Makes Little Sense”

The federal obstruction statute under which McHugh and others have been charged, 18 U.S.C. 1512, reads as follows:

(c) Whoever corruptly —

(1) alters, destroys, mutilates, or conceals a record, document, or other object, or attempts to do so, with the intent to impair the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding; or

(2) otherwise obstructs, influences, or impedes any official proceeding, or attempts to do so,

shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

Like other defendants, McHugh had argued that the statute doesn’t apply for two key reasons: the counting of Electoral College votes isn’t an official proceeding, and that the wording of the statute is unconstitutionally vague.

Bates didn’t buy either argument.

As to McHugh’s “official proceeding” argument, Bates made his alignment with his District Court colleagues clear.

“Following the lead of five other judges in this District, the Court rejects both of McHugh’s contentions,” Bates writes. “His narrow interpretation of ‘official proceeding’ is unsupported by statutory text and makes little sense applied to congressional proceedings. Instead, the Court holds that a ‘proceeding before the Congress’ must merely be a formal assembly of Congress convened for the purpose of conducting official business that involves some other entity as an integral component. Applying this standard to the January 6th Certification, the Court readily concludes that it was an official proceeding.”

In his memorandum, Bates undertakes an analysis of whether the certification is a proceeding of Congress or a proceeding before Congress, and concludes that it is, in fact, both.

“That no less an authority than the Constitution of the United States mandates the proceeding’s occurrence, see U.S. Const. amend. XII, and that everything from the specific date to the seating arrangements to the time allotted for debate is prescribed by statute, see 3 U.S.C. §§ 15–17, only confirms that this was a formal assembly of the Congress for the purpose of conducting official business,” Bates writes.

“As Judge Friedrich noted in Sandlin, ‘the certificates of electoral results are akin to records or documents that are produced during judicial proceedings, and any objections to these certificates can be analogized to evidentiary objections,'” Bates also writes. “The Court agrees that this analogy is apt, and it underscores that the electors and their votes are just as much ‘before’ Congress as litigants are ‘before’ a court or regulated parties are ‘before’ an agency. The January 6th Certification was a ‘proceeding before the Congress.'”

Bates says that McHugh’s arguments about vagueness also miss the mark.

“Running throughout McHugh’s briefing is a fundamental—if understandable— misunderstanding of the vagueness doctrine,” Bates writes. “There is a crucial difference between reasonable people differing over the meaning of a word and reasonable people differing over its application to a given situation—the latter is perfectly normal, while the former is indicative of constitutional difficulty.”

The Meaning of “Temporarily Visiting”: A First-Time Legal Analysis

McHugh also challenged charges relating to him being in a restricted building or grounds. Specifically, McHugh was charged with violating 18 U.S.C. 1752, which defines “restricted buildings or grounds” as follows:

(c) In this section—

(1) the term “restricted buildings or grounds” means any posted, cordoned off, or otherwise restricted area—

(A) of the White House or its grounds, or the Vice President’s official residence or its grounds;

(B) of a building or grounds where the President or other person protected by the Secret Service is or will be temporarily visiting; or

(C) of a building or grounds so restricted in conjunction with an event designated as a special event of national significance; and

(2) the term “other person protected by the Secret Service” means any person whom the United States Secret Service is authorized to protect under section 3056 of this title or by Presidential memorandum, when such person has not declined such protection.

Prosecutors charged McHugh under this statute because then-Vice President Mike Pence, a “person protected by the Secret Service,” was “temporarily visiting” the Capitol during the riot on January 6th.

McHugh argued that only the U.S. Secret Service can create restricted areas under the statute, and that Pence was not “temporarily visiting” the Capitol within the terms of the statute.

Bates rejected both of these arguments. He first agreed with McFadden’s analysis in two other Jan. 6 cases that an area does not need to be established by the U.S. Secret Service in order to qualify as a “restricted building or grounds.”

The issue of whether Pence was “temporarily visiting” was, Bates said, an issue of first impression.

“So far as the Court can tell, this argument is novel—no court has ever been asked to interpret the phrase ‘temporarily visiting’ in § 1752(c)(1)(B),” Bates writes in his ruling, before undertaking separate analyses of the words “temporarily” and “visit.” After concluding that “one can be ‘temporarily visiting’ a place for any reason, so long as the visit is (or is intended to be) ‘relatively short,'” he then made the “commonsense conclusion” that Pence was, indeed, temporarily visiting the Capitol on Jan. 6.

McHugh had argued that Pence could not have been “temporarily visiting” the Capitol that day because he kept a permanent office inside the building, and “the phrase ‘temporarily visiting’ connotes temporary travel to a location where the person does not normally live or work on a regular basis.”

Bates called McHugh’s characterization “more than a little misleading,” and noted that the Vice President’s “working office is in the West Wing of the White House, and she also maintains a ceremonial office in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building.”

“This state of affairs reflects what anyone with a working knowledge of modern American government intuitively understands: the Vice President is principally an executive officer who spends little time at the Capitol and likely even less in her ‘office’ there,” Bates writes. “So although there is a well-appointed room at the Capitol ‘formally set aside . . . for the vice president’s exclusive use,’ that fact in its proper context does not transform the Capitol into the Vice President’s ‘place of employment.’ Even if there is some carveout in § 1752 for where a protectee normally lives or works, it does not apply to Vice President Pence’s trip to the Capitol on January 6, 2021.”

Although several judges have now rejected motions to dismiss the obstruction charge, at least one group of defendants isn’t giving up: co-defendants Ethan Nordean, Joseph Biggs, Charles Donohoe, and Zachary Rehl, alleged members of the Proud Boys extremist group, have appealed Kelly’s denial.

Read Bates’ ruling, below.

[Images via FBI.]