The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear various cases related to the controversial doctrine of qualified immunity for police officers in a series of orders released Monday morning.

Punting again on the issue, the court was quickly upbraided by critics of the doctrine from various ideological camps.

“This is, to put it bluntly, a shocking dereliction of duty,” Cato Policy Analyst Jay Schweikert said in a statement provided to Law&Crime. “There was simply no excuse for the Court to decline this golden opportunity to begin addressing its mistakes in creating and propagating the doctrine of qualified immunity.”

“It’s unfortunate that the Supreme Court has declined to consider ending qualified immunity protection, which was invented by the court and has no basis in statute,” said Center for American Progress Vice President for Criminal Justice Reform Ed Chung. “The doctrine in its current form stacks the deck against victims.”

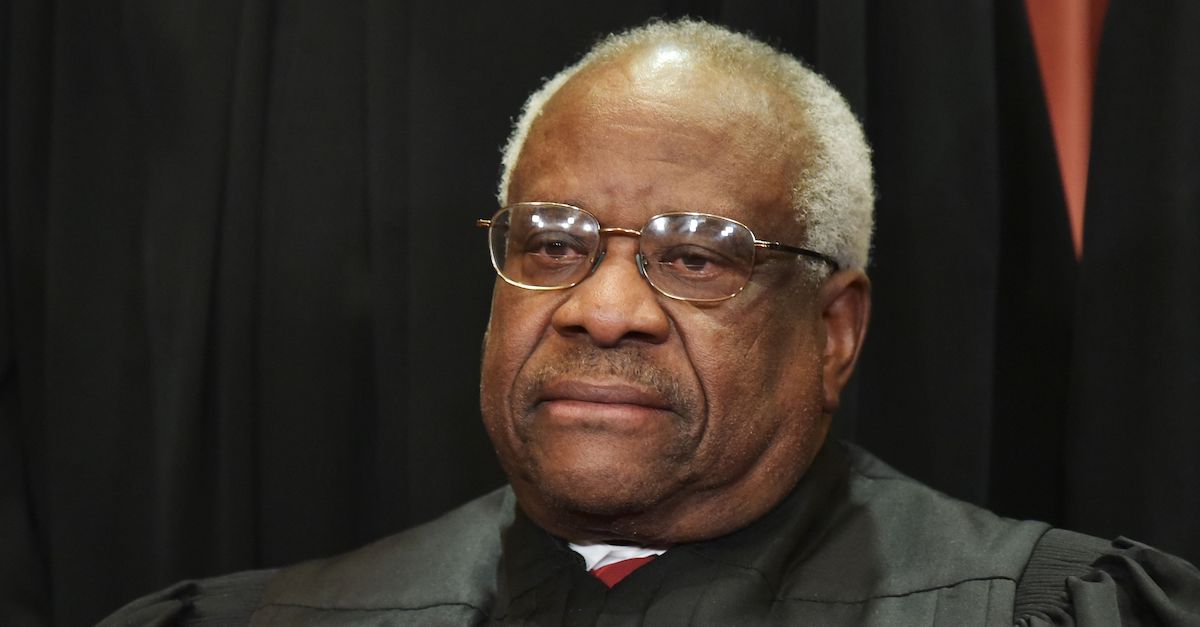

Conservative Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a dissenting opinion to the denial of certiorari–calling the doctrine into question because the court’s jurisprudence “appears to stray from the statutory text.”

“I continue to have strong doubts about our §1983 qualified immunity doctrine,” Thomas wrote. “Given the importance of this question, I would grant the petition for certiorari.”

The doctrine of qualified immunity for police officers was created by “activist” judges on the typically liberal Earl Warren Court in the 1967 case of Pierson v. Ray. In that case, an 8-1 majority of the justices read an immunity defense into the Civil Rights Act of 1871–which is also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871.

Thomas explains that this law was meant to “secure certain individual rights against abuse by the States” and was structured to enforce the provisions of the Reconstruction Era Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments.

The first section of that law, codified at 42 U.S.C. §1983, provides:

[A]ny person who, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage of any State, shall subject, or cause to be subjected, any person within the jurisdiction of the United States to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution of the United States, shall…be liable to the party injured in any action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress…

“Put in simpler terms, [Section 1983 gives] individuals a right to sue state officers for damages to remedy certain violations of their constitutional rights,” Thomas notes.

For nearly 100 years, §1983 was undisturbed by judicial interpretation–and was also rarely used due to incorporation issues.

When Civil Rights protesters attempted to use the statute to petition for redress against Southern police officers and a judge, however, the Supreme Court fashioned qualified immunity in order to limit the reach and impact of the post-bellum attempt at radical reform.

The modern version of the doctrine holds:

Qualified immunity shields federal and state officials from money damages unless a plaintiff pleads facts showing (1) that the official violated a statutory or constitutional right, and (2) that the right was “clearly established” at the time of the challenged conduct.

But that concept appears nowhere in the text of the law itself.

“The text of §1983 ‘ma[kes] no mention of defenses or immunities,'” Thomas points out. “Instead, it applies categorically to the deprivation of constitutional rights under color of state law.”

Since then, the doctrine has grown exponentially by subsequent court decisions which make it exceedingly difficult for plaintiffs to bring police officers to trial for alleged constitutional violations.

Thomas details some of the doctrine’s genesis, reach and progeny:

The Court derived this defense from “the background of tort liabilit[y] in the case of police officers making an arrest.” These decisions were confined to certain circumstances based on specific analogies to the common law.

Almost immediately, the Court abandoned this approach. In Scheuer v. Rhodes, without considering the common law, the Court remanded for the application of qualified immunity doctrine to state executive officials, National Guard members, and a university president. It based the availability of immunity on practical considerations about “the scope of discretion and responsibilities of the office and all the circumstances as they reasonably appeared at the time of the action on which liability is sought to be based,” rather than the liability of officers for analogous common-law torts in 1871.

The dissent then briefly attacked even the basic idea that the extension of the qualified immunity doctrine stems from anything in the common law—saying that such extensions of the highly criticized doctrine actually appear to stem from an-also controversial framework that balances “litigation costs and efficiency.”

Thomas argued that the nation’s high court should “at least” consider returning to the method of determining whether qualified immunity would have attached to official behavior “in an analogous” set of circumstances under the common law.

“The Court has continued to conduct this inquiry in absolute immunity cases, even after the sea change in qualified immunity,” Thomas wrote. “We should do so in qualified immunity cases as well.”

The Supreme Court has been hard pressed by both outside criticism and by various petitions for writs of certiorari to reconsider its decades-old juridical creation of the qualified immunity doctrine.

For some, Monday’s denial could be seen as a signal that most of the justices don’t believe that the Court’s own work needs correcting. For others, the upshot was not difficult to ascertain: the Supreme Court’s dodging of qualified immunity issues is a signal to the House and Senate that legislators should clarify the law to fix the problem–if lawmakers think there is one.

Longstanding opponents of the doctrine, such as the U.S. libertarian vanguard, slammed the court for effectively deferring to Congress.

“In the tumultuous wake of George Floyd’s brutal death at the hands of Minneapolis police, this development could not come at a worse time,” Schweikert’s statement continues. “The senseless violence committed by Derek Chauvin—and the stunning indifference of the officers standing by as George Floyd begged for his life—is the product of our culture of near-zero accountability for law enforcement. And while this culture has many complex causes, one of the most significant is qualified immunity.”

“By effectively rewriting and undermining the civil rights law that was supposed to be our primary means of holding public officials accountable, the Supreme Court shares a huge portion of the blame for our present crisis. Qualified immunity will go down in history as one of the Supreme Court’s most egregious, costly, and embarrassing mistakes. None of the Justices on the Court today were responsible for creating this doctrine, but they all had a responsibility to fix it—and except for Justice Thomas, they all shirked that responsibility. It is now all the more urgent that Congress move forward on this issue to ensure that all public officials—especially members of law enforcement—are held accountable for their misconduct.”

Chung also called on legislators to pick up the issue of qualified immunity but cautioned that there was already trouble with that approach.

“Congress now has the opportunity to enact legislation that would take down this shield and end qualified immunity for law enforcement officers,” he said. “Unfortunately, some conservative lawmakers have already signaled their intent to oppose it, calling it a ‘poison pill.’ They are standing in the way of critical reforms that would go a long way to holding police officers accountable for their actions.”

[image via MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images]