It’s fun to follow along with the federal criminal bribery statute to see how closely U.S. Ambassador to the EU Gordon Sondland ‘s testimony tracks with each element. As Law&Crime noted earlier, Sondland’s testimony did admit some of the required statutory elements. But it’s important to remember that criminal bribery and the impeachable offense of bribery, as enshrined in the Constitution, are two different things.

During Sondland’s testimony Wednesday, House Intelligence Committee Chairman Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.), asked the witness whether the White House meeting had been conditioned on the Ukrainians’ announcement of investigations into the Bidens and the CrowdStrike conspiracy theory. Sondland answered that he had indeed been such a quid pro quo. That testimony closed the circle on Schiff’s closing remarks on Tuesday, in which he explained that under criminal law, bribery requires, “the conditioning of an official act for something of value.”

While we’re talking criminal law, this is a good time to point out that trying to condition an official act for something of value would also be illegal – and would be called “attempted bribery.”

Recently, the Supreme Court of the United States handed down a ruling in a case that had major repercussions on the world of political corruption; in 2016, SCOTUS unanimously ruled in McDonnell v. United States that former Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell’s corruption convictions should be vacated, because his having merely set up a meeting wasn’t enough to constitute an “official act” within the context of bribery. Once the SCOTUS ruling was handed down, the corruption dominoes began to fall. New York State officials Sheldon Silver, Dean Skelos, and Adam Skelos had their corruption convictions overturned, and charges against U.S. Senator Bob Menendez (D-N.J.) were dismissed. The McDonnell ruling might be relevant to a prosecution for conditioning a White House meeting on political assistance – but it’s tough to see how it would have any bearing on the same conditioning of the Ukrainian military aid package.

Schiff, however, isn’t presiding over a criminal prosecution for bribery or anything else. Sitting presidents are immune from criminal prosecution. We’re knee-deep in impeachment proceedings — and while there is significant crossover between the world of impeachment and that of criminal law, the two are two different things.

Whatever credible arguments might be made about the precise matching of facts with required statutory elements of bribery, there are none relating to bribery as an impeachable offense. Regardless of the tantalizing manner many of Donald Trump’s supporters have attempted to spin impeachment as though it should require some higher standard of proof due to the momentous consequences for our nation, the reality is just the opposite. Impeachment does not require “elements.” It requires nothing more than an agreement among enough members of Congress that the president has misused their authority.

When it comes to impeachment, the rules of the game are far looser than those of a criminal trial. The Constitution, in Article II, Section 4, specifically demands that the president “shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” “Treason” gets a specific definition in Article III, Section 3; neither “bribery” nor “high crimes and misdemeanors” are elaborated upon in the rest of the document.

During the time of the Founding Fathers, there was no federal statute defining bribery; one wasn’t adopted until 1853. What, exactly, “bribery” as an impeachable offense means must be established by context. In a 1716 treatise on English law (which would have been something relied upon by those drafting the Constitution), bribery was described as follows:

Bribery in a large sense is sometimes taken for the receiving or offering of any undue reward, by or to any person whatsoever, whose ordinary profession or business relates to the administration of publick justice, in order to incline him to do a thing against the known rules of honesty and integrity; for the law abhors any the least tendency to corruption in those who are any way concerned in its administration, and will not endure their taking a reward for the doing a thing which deserves the severest of punishments.

That’s a far broader definition of “bribery” than what would be required of a modern federal statute; under 18th Century standards, bribery is a general term used to indicate official misuse of authority. The circumstances of the Trump-Ukraine allegations, supported by testimony from Sondland and others, fit squarely within the scope of conduct prohibited when presidential impeachment guidelines were drafted.

Did the Framers mean for impeachable offenses to mirror criminal ones? No, and that’s a question that was already asked and answered more than a century ago.

In 1912, Judge Robert Wodrow Archbald was impeached for taking bribes from those who came before him in court. In the House Judiciary Committee’s report on Judge Archbald’s impeachment, it elaborated on the meaning of “bribery” as well as on the relationship between statutory crimes and impeachable offenses:

if Congress … failed to pass an act in reference to the crime of bribery, as it did fail for more than a year after the Constitution went into operation, it would result that no officer would be impeachable for either crime, because Congress had failed to pass the needful statutes defining crime in the case of bribery and prescribing the punishment in the case of treason as well as bribery. It can hardly be supposed that the Constitution intended to make impeachment for these two flagrant crimes depend upon the action of Congress.

In other words, just because there’s no criminal statute forbidding some act does not mean that a person can’t be impeached for that same act.

Let’s keep in mind, too, that the Constitution lists bribery (along with treason) as the precursors to “or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” As I’ve explained before, “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” equated to general misuse of official authority.

Harvard Law Professor Noah Feldman conducted extensive research on James Madison’s involvement in the the drafting of impeachment language. The “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” wording was something of a compromise between members of the Constitutional Convention who wished to use “maladministration” (18th century for “doing a lousy job”) and Madison, who wished to use something more specific so as not to pose a serious risk that every president might be impeached.

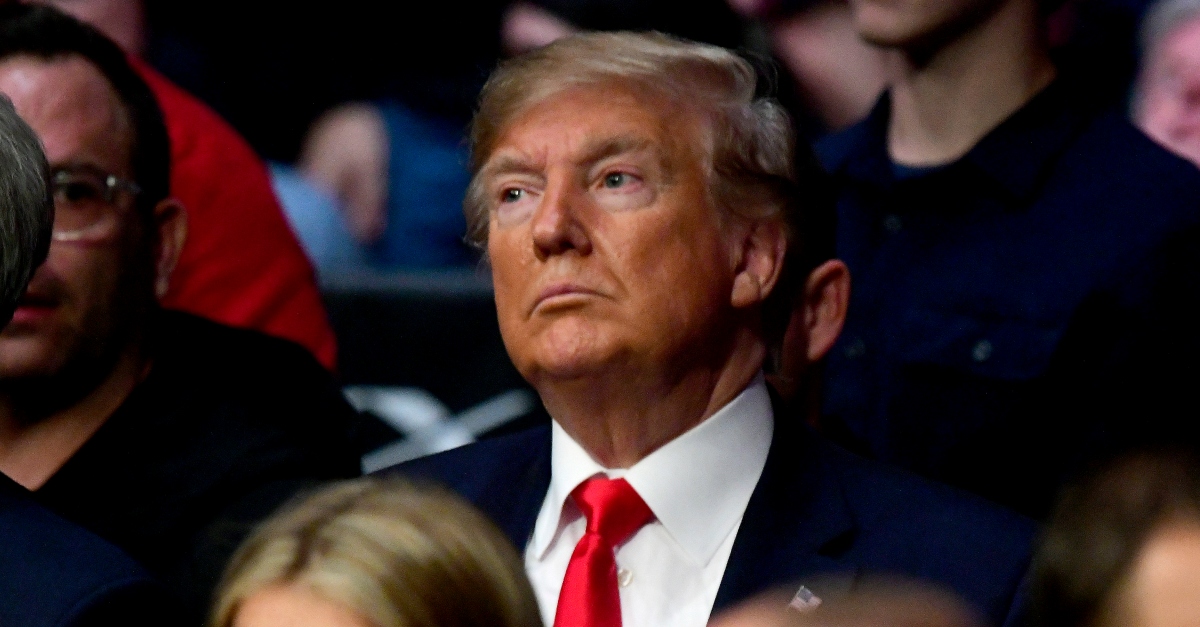

[Image via Steven Ryan/Getty Images]