A volunteer holds a sticker which reads “Ohio Voted” at a polling place in 2020. (Photo by Ty Wright/Getty Images.)

In a 4-3 decision, the Ohio Supreme Court on Wednesday struck down House and Senate district maps drawn by a Republican-led redistricting commission that was required by a new constitutional amendment to be fair.

Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor, a Republican, broke from her duly noted party affiliation to join the state high court’s Democrats in rubbishing the GOP-designed maps. The court’s Democrats, Michael P. Donnelly, Melody J. Stewart, and Jennifer L. Brunner, joined O’Connor to round out the majority.

Writing for the four-judge majority, Justice Stewart recapped the litigation — and the relevant law — as follows:

Respondent Ohio Redistricting Commission adopted a General Assembly–district plan in September 2021 to be effective for the next four years. The complaints in these three cases allege that the plan is invalid because the commission did not comply with Article XI, Sections 6(A) and 6(B) of the Ohio Constitution, which require the commission to attempt to draw a plan that meets standards of partisan fairness and proportionality. In one case, the challengers also allege that the plan violates the Ohio Constitution’s guarantees of equal protection, assembly, and free speech.

The court held that the proffered maps violated the “proportionality standard” in Article XI, Section 6(B). It also held that “the commission did not attempt to draw a plan that meets the standard in Section 6(A) — that no plan shall be drawn primarily to favor a political party.”

The court did not decide whether the maps violated “the rights to equal protection, assembly, and free speech guaranteed under the Ohio Constitution,” thus skirting the more vexing issues.

“We order the commission to be reconstituted and, within ten days of this judgment, to adopt a new plan in conformity with the Ohio Constitution,” the court ruled.

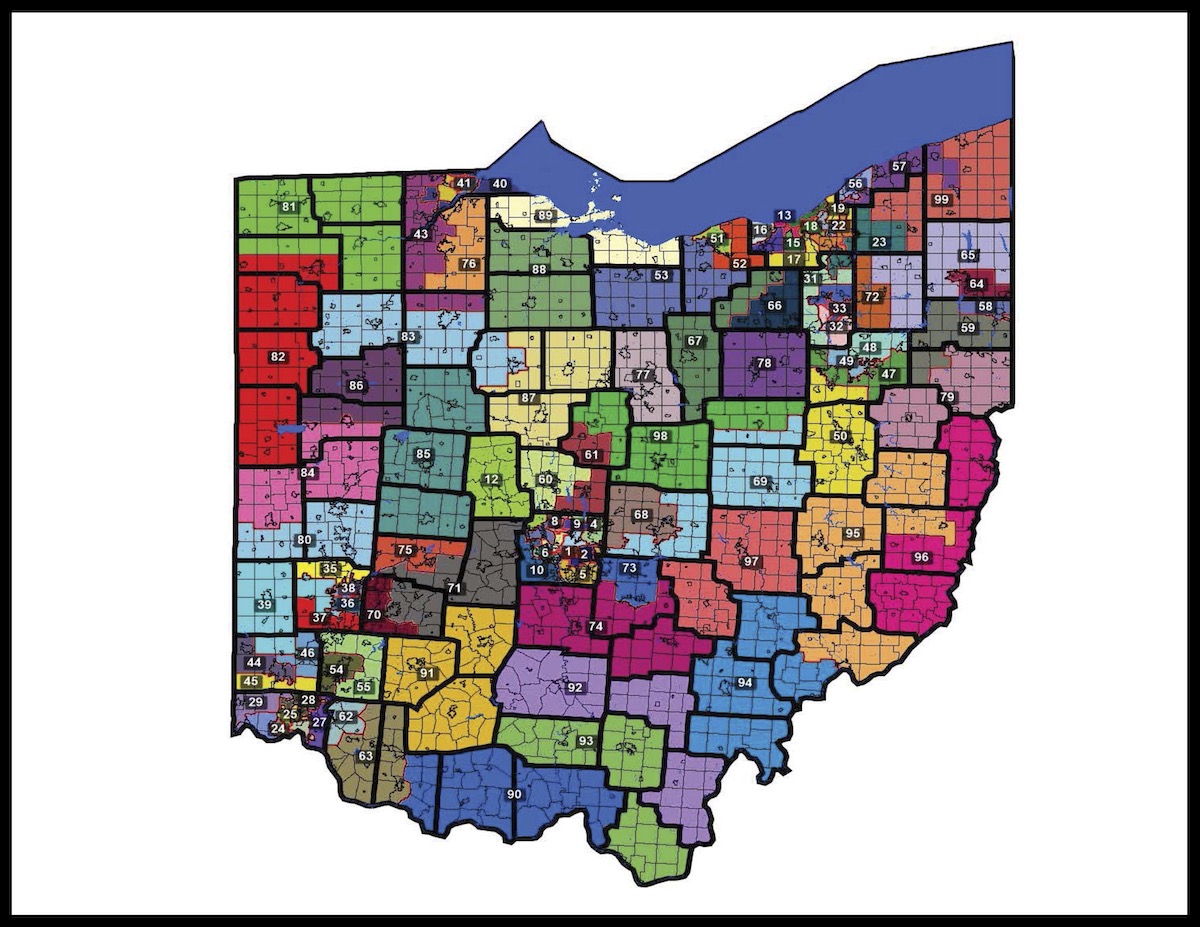

Ohio House of Representatives districts are seen in a district map rubbished by the Ohio Supreme Court. (Image via the Ohio Redistricting Commission.)

Justices Donnelly and Brunner concurred with separate opinions. O’Connor also concurred in an opinion joined by Brunner.

Republicans Sharon L. Kennedy and Patrick F. Fischer dissented via their own opinions. Richard Patrick “Pat” DeWine joined Kennedy’s dissent.

Ohio Supreme Court justices are elected in nominally nonpartisan contests but are generally nominated and endorsed by a political party.

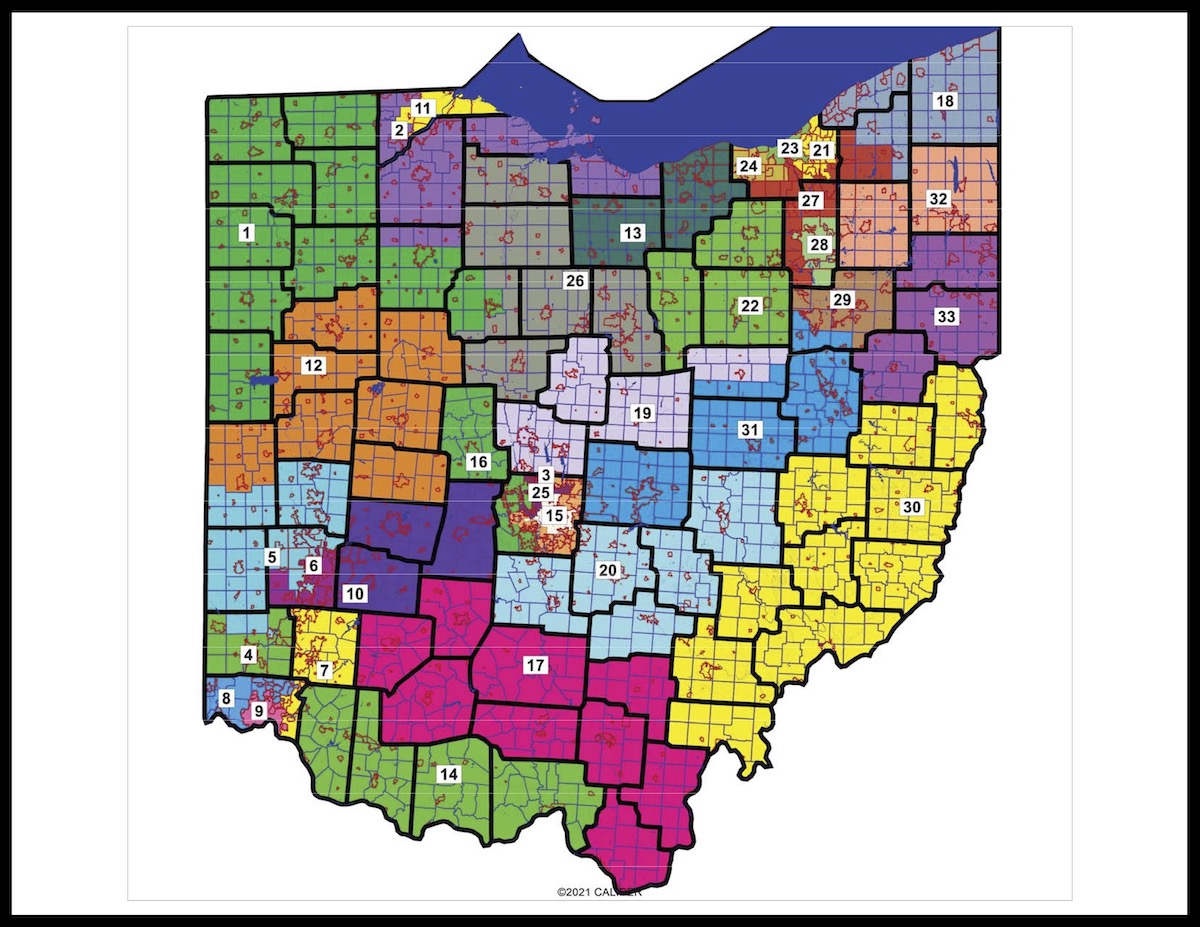

Ohio Senate districts are seen in a district map rubbished by the Ohio Supreme Court. (Image via the Ohio Redistricting Commission.)

The majority immediately noted that a similar case in 2012 failed because it was based on a previous version of the state constitution. The legislature elected under the old version of Article XI remained seated until 2020.

In November 2015, the court noted, “Ohio voters overwhelmingly approved an amendment to the Ohio Constitution that repealed former Article XI and replaced it with a new version, which established a new process for creating General Assembly districts.”

The court then expounded on the meaning of the change:

The amendment provided for the creation of a seven-member Ohio Redistricting Commission, composed of the governor, the auditor of state, the secretary of state, one person appointed by the speaker of the House of Representatives, one person appointed by the House minority leader, one person appointed by the Senate president, and one person appointed by the Senate minority leader. The commission is responsible for redistricting the boundaries of the 99 districts of the House of Representatives and the 33 Senate districts in any year ending in the numeral one — after the release of the federal decennial census.

The majority then cited Article XI, Section 6 of the State Constitution to again lay out the ground rules:

The Ohio redistricting commission shall attempt to draw a general assembly district plan that meets all of the following standards:

(A) No general assembly district plan shall be drawn primarily to favor or disfavor a political party.

(B) The statewide proportion of districts whose voters, based on statewide state and federal partisan general election results during the last ten years, favor each political party shall correspond closely to the statewide preferences of the voters of Ohio.

(C) General assembly districts shall be compact.

Nothing in this section permits the commission to violate the district standards described in Section 2, 3, 4, 5, or 7 of this article.

The court then rubbished the upshot which resulted when Ohio lawmakers actually attempted to implement the constitutional goals:

On August 6, 2021, the governor convened the first meeting of the Ohio Redistricting Commission. The commission consisted of respondents Governor Mike DeWine, Secretary of State Frank LaRose, Auditor of State Keith Faber, Speaker of the House Robert Cupp, and President of the Senate Matthew Huffman—who are members of the Republican party—and House Minority Leader Emilia Sykes and Senator Vernon Sykes—who are members of the Democratic party. House Speaker Cupp and Senator Sykes were appointed as commission cochairs. Other than administering oaths of office and announcing that the commission would schedule public hearings, the commission did not conduct any business on August 6.

Between August 23 and August 27, the commission held multiple hearings during which members of the public gave input about the redistricting process.

The commission held its second meeting on August 31—one day before the deadline to adopt a final district plan. Senator Sykes presented a proposed district plan drafted by the Senate Democratic Caucus. After a presentation by a map drawer from the caucus, the commission members had a discussion that suggested that they had not yet agreed on a process for drafting a district plan. House Minority Leader Sykes asked when the commission intended to present a proposed plan for public comment. House Speaker Cupp replied that a district plan was “being developed” but would not be available by the September 1 deadline due to a delay in receiving census data. Leader Sykes asked who was participating in drafting that plan and when she could expect to participate in the process. She also quoted the portion of Section 1(C) stating that the “commission shall draft the proposed plan.”

What follows in the opinion is a lengthy recitation of the commission’s specific acts and failures. The court repeatedly noted that many — if not all — of the commission’s internal votes were “along party lines” and that even some of the commission’s members (including Gov. DeWine) lamented that the process — and the resulting maps — were both littered with “shortcomings.”

Several of the named defendants in the case, including Senate President Huffman and House Speaker Cupp, argued that Article XI, Section 6 of the state constitution was “not mandatory but merely ‘aspirational,'” the court said.

“[T]the evidence—much of which is undisputed—shows that the commission did not attempt to comply with the standards stated in Article XI, Section 6(A) or 6(B),” the majority concluded. “Moreover, respondents’ arguments are unpersuasive. Section 6 imposes enforceable duties on the commission.”

The majority continued:

At bottom, the process that culminated in the adopted plan, having been directed and controlled by one political party’s legislative leaders, was not an attempt to comply with Section 6(A) or 6(B) standards. When a single party exclusively controls the redistricting process, “it should not be difficult to prove that the likely political consequences of the reapportionment were intended.”

Further, the expert evidence supports the conclusion that the adopted plan’s partisan skew cannot be explained solely by nondiscriminatory factors. Under the adopted plan, Republicans are favored to win between 61 and 68 House seats and between 20 and 24 Senate seats. The expert report of Dr. Michael Latner, a professor of political science at California Polytechnic State University with expertise in electoral-system design and statistical methods in elections and in designing electoral districts, shows that the plan substantially favors Republican voters through targeted “cracking” and “packing” of Democratic voters that “did not occur by chance or accident.”

Another expert who “generated 5,000 possible district plans” using the constitutional criteria found that “none was as favorable to Republicans as the adopted plan” that wound up before the court, the opinion states. “The fact that the adopted plan is an outlier among 5,000 simulated plans is strong evidence that the plan’s result was by design.”

Given a swiftly approaching election cycle which requires candidates to submit petitions and declarations by Feb. 2, 2022, the high court ordered the commission to come up with a new map within ten days. The court also retained jurisdiction to review the new map “for compliance with” the state constitution.

Justice Kennedy’s dissent suggested that the court did not have the power to invalidate the commission’s plans due to what he believed were constraints upon the court imposed by the state constitution.

Justice Fischer agreed with Kennedy but went a slight step further.

“I am strongly convinced,” he wrote, “that it is not even necessary for us to engage in an analysis of the merits of these cases. The text of the Ohio Constitution is clear, and given the allegations in the complaints, this court lacks the authority to act as requested by the petitioners bringing these cases.”

The case is League of Women Voters of Ohio v. Ohio Redistricting Comm., Slip Opinion No. 2022-Ohio-65. Read the full set of opinions and dissents, 146 pages in all, below:

Editor’s note: legal citations have been omitted from quotes.