Andy Beshear celebrates after defeating incumbent Matt Bevin for governor on November 5, 2019 in Louisville, Kentucky.

Three people of faith in Kentucky alleged in a class action complaint on Tuesday that Gov. Andy Beshear, a Democrat, went way too far with coronavirus-related restrictions. The plaintiffs noted in the opening lines of their lawsuit that “in times of public panic and fear, egregious violations of fundamental rights have been permitted throughout the history of this Country.”

The plaintiffs, Theodore Roberts, Randall Daniel and Sally O’Boyle, cited to Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944), an infamous Supreme Court decision which upheld the U.S. government’s decision to put Japanese-Americans in certain internment camps during World War II. The church attendance lawsuit is filed against Gov. Beshear, Boone County Attorney Robert Neace and Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services Acting Secretary Eric Friedlander in their official capacities.

According to the 19-page complaint, the coronavirus threat poses a “serious threat to public health,” but orders from the governor also pose a threat to constitutional rights to such a degree that, if permitted to stand, they will set an odious precedent that will only be recognized as an “error” well after the fact. The analogy the plaintiffs draw is that Korematsu was harshly rebuked in the Trump travel ban case, Trump v. Hawaii, 138 S.Ct. 2392 (2018), many decades after Korematsu was decided.

Recall: the Supreme Court repudiated, but under most interpretations did not fully overturn, Korematsu when it upheld the Trump travel ban in a 2018 5-4 opinion. As is par for the course, the court’s liberals and conservatives were deeply divided on the issue. Chief Justice John Roberts saw fit to condemn Korematsu while also distancing the Trump v. Hawaii decision from it:

Finally, the dissent invokes Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214 (1944). Whatever rhetorical advantage the dissent may see in doing so, Korematsu has nothing to do with this case. The forcible relocation of U. S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority. But it is wholly inapt to liken that morally repugnant order to a facially neutral policy denying certain foreign nationals the privilege of admission. The entry suspension is an act that is well within executive authority and could have been taken by any other President—the only question is evaluating the actions of this particular President in promulgating an otherwise valid Proclamation.

The dissent’s reference to Korematsu, however, affords this Court the opportunity to make express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—“has no place in law under the Constitution.” 323 U. S., at 248 (Jackson, J., dissenting).

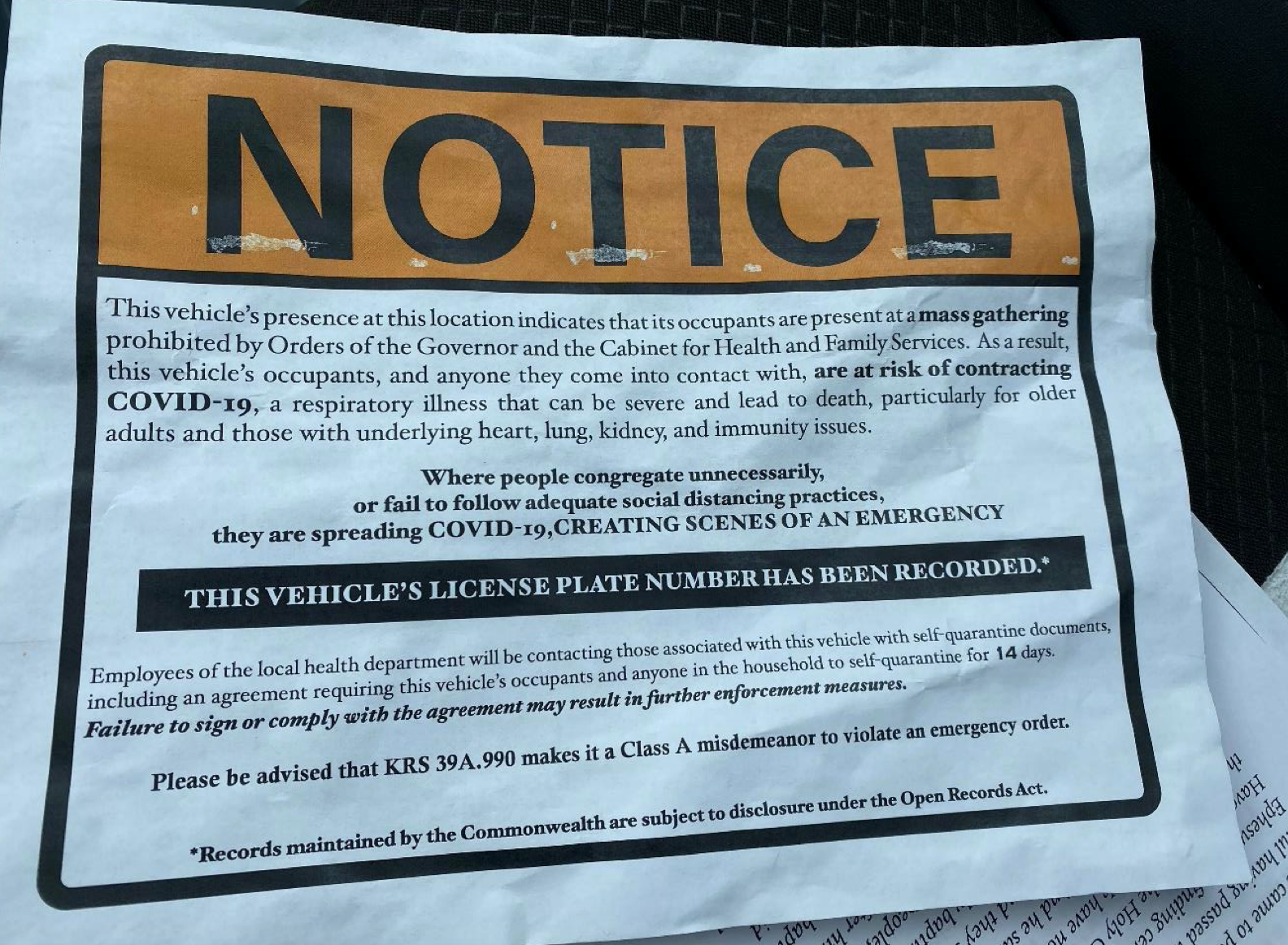

The plaintiffs in the class action suit we now discuss each asserted that in-person church worship is “central” to their faith. They said they attended an Easter Sunday service at Maryville Baptist Church “pursuant to sincerely held religious beliefs that in-person church attendance was required, particularly on Easter Sunday.” Despite acting in accordance with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines during the Easter Sunday service, each of them sitting “six feet away from other congregants at the service, [wearing] masks covering their faces, and […] not hav[ing] personal contact with others attending,” they were greeted upon their exit with notices on their cars.

The plaintiffs all but said that Gov. Beshear has engaged in do-as-I-say-but-not-as-I-do hypocrisy.

“Kentucky State Police have solely been dispatched by the Governor, and those reporting to him and acting at his behest, to harass, charge, intimidate, and threaten the churchgoers from Maryville Baptist Church and other church services, and not to any other public gatherings, including, without limitation, the Governor’s own public daily gathering where he gives his press release,” they argued:

“Among other things, the Quarantine and Prosecution Notice requires a self-quarantine of two weeks, and threatens criminal action against any vehicle owner whose vehicle was found at the church, including each of the Plaintiffs. It does so regardless of whether: (i) any Plaintiff has contracted the disease; (ii) there is any particular assessment of the likelihood of contracting the disease from the activity in question; and (iii) Plaintiffs took the safety precautions as described above so as to make their contracting the disease unlikely.”

“None of the Plaintiffs have displayed any symptoms of the COVID-19 disease, and, to the best of their knowledge, they do not have and have not contracted the COVID-19 disease,” the complaint continued. “All of the Plaintiffs refuse to self-quarantine as required by the Quarantine and Prosecution Notice, unless or until they have a diagnosis of them having contracted COVID-19, which none of them have.”

Roberts, Daniel, and O’Boyle claimed they “reasonably fear prosecution if they should attend further church services in light of the notice” and “fear prosecution and/or the equivalent of house arrest with quarantine, in light of the Quarantine and Prosecution Notice.”

All told, the plaintiffs claimed the defendants violated their First Amendment rights to free exercise of religion, their Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments rights to procedural due process, and their constitutionally protected rights to travel.

The root of the complaint is that in-person church attendance which observes CDC guidelines should be allowed, especially when a number of other activities the government deems legally essential also place people into close contact.

“Defendants’ prohibition of any in person church services, in the name of fighting Covid-19, is not generally applicable,” the lawsuit said. “There are numerous exceptions to the March 19, 2020 Order, such as an exception for factories, or attending establishments like shopping malls, where far more people come into closer contact with less oversight.”

The plaintiffs and their attorney, Christopher Wiest, are asking the U.S. District Court of Eastern Kentucky to certify the class, declare the defendants’ orders unconstitutional, and bar the enforcement thereof.

Lawsuit against Kentucky Go… by Law&Crime on Scribd

[Image via John Sommers II/Getty Images]