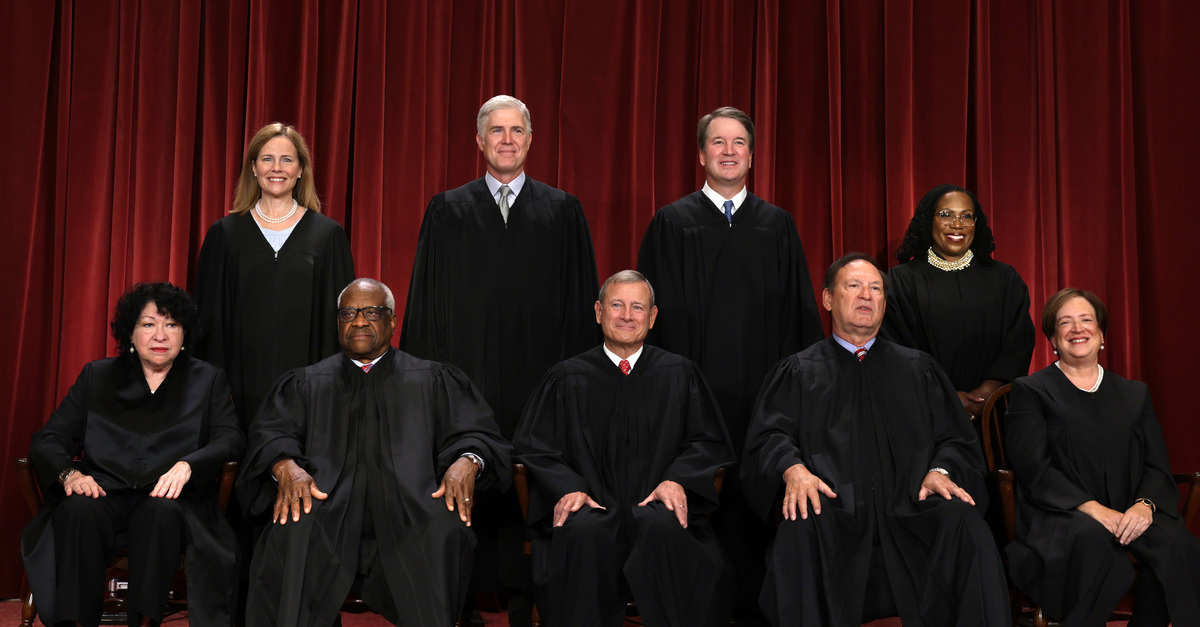

United States Supreme Court (front row L-R) Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan, (back row L-R) Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments Tuesday in National Pork Producers Council v. Ross, a dispute over California’s 2018 animal welfare law that could send pork prices skyrocketing.

California’s Proposition 12 bars the sale of uncooked pork products when the seller knows or should know that the meat came from a breeding pig that was confined “in a cruel manner.” As a practical matter, the regulation means that the animals in question must have at least 24 square feet of living space, which is substantially more than the typical “gestation crates” used in commercial pork production. Under the law, violators are subject to fines and prison time for each sale. The law, if allowed to go into effect, would apply whether the animals were raised inside or outside California.

The National Pork Producers Council and the American Farm Bureau Federation sued and argued that California’s law violates the “dormant” Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution. The dormant Commerce Clause refers to the Constitution’s implicit limitation on state legislation of commerce; because exclusive control over interstate commerce is explicitly given to Congress, any state action that discriminates against interstate commerce improperly conflicts with federal authority.

The challengers argue that the greatest impact of California’s regulation will be felt outside the Golden State, given that nearly all the pork consumed in California originates in other states. They say that the strict regulation would wreak havoc on pork production by requiring massive increases in production costs across the industry.

By contrast, California argues that nothing about its law was intentionally discriminatory against out of state producers, and that those producers that refuse to adhere to California’s standards can simply sell their products elsewhere.

The law’s challengers lost their case at both the district court and circuit court levels, but Proposition 12 has not been in effect while the litigation is pending. SCOTUS now considers the case at the pleading phase to decide whether the pork producers’ case can survive to move toward trial.

Attorney Timothy Bishop argued for petitioners that if Proposition 12 is allowed to stand, “The only safe course is to raise all pigs the California way,” which would “abandon the framers’ idea of a national market.”

The justices, however, did not give Bishop’s argument a particularly warm reception over the two hours of proceedings.

Justice Elena Kagan pressed Bishop on how broadly his argument could go, and queried, “so any time a state does something that forces you to change production methods in any way, that would be banned?”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson noted that Bishop’s oral argument appeared to diverge from the argument articulated in his written brief.

“Which is it?” Jackson asked.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor brought the conversation to the potential state interests involved.

“We have briefs from scientists that point out that there are some genuine scientific reasons for fearing the raising of pigs,” Sotomayor said to Bishop. Sotomayor then went a step farther, and raised concerns that particularly resonate in the post-COVID period.

“Many may disclaim it, but some people could reasonably believe that close confinement of farm animals increases the likelihood of new diseases jumping from animals to humans. We know that is happening,” said the justice, adding, “There is certainly a reasonable basis for people to think this.”

“We don’t think so. Our veterinarians say the opposite,” responded Bishop.

A skeptical Justice Neil Gorsuch pressed Bishop on the propriety of having a court adjudicate a dispute that perhaps is better left to Congress.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh raised yet another concern with Bishop’s argument: that a ruling in Bishop’s favor on dormant Commerce Clause would require a re-tooling of the Supreme Court’s interpretation of two other portions of the Constitution — the Import/Export Clause and the Privileges and Immunities Clause.

“It would seem to me you can’t do one without the other,” commented Kavanaugh.

As the justices fired questions at lawyers for the Biden administration, California, and the Humane Society, conversation turned largely to the question of just how far one state can legally go to affect conduct in other states. In particular, many of the justices zeroed in on whether state regulations based on a moral objection should be analyzed with the same criteria as those based on health and safety objections.

Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler on behalf of the Department of Justice said the pork producers should have the opportunity to prove their case, but he said DOJ takes no position on whether California might ultimately prevail in making a sufficient showing of state interest to uphold the regulation.

Justice Samuel Alito asked Kneedler whether a state’s safety interests should be treated different than its moral interests.

“Does that distinction really work?” Alito asked. “California adopted this to avoid the feeling of moral complicity that they would experience if they purchased and consumed pork that had been produced in what they regarded as an inhumane way.”

Kagan jumped in to offer a relevant example and asked, “Would it be impermissible if a state said they wouldn’t traffic in products being produced by slavery?”

The justice then followed up by asking whether a state might, for reasons of morality, ban the sale of horse meat (a line of inquiry with some crossover to a 2012 case authored by Kagan in which SCOTUS decided 9-0 to strike down a California law regulating livestock on the basis that the law was preempted by a federal livestock statute).

Alito asked Kneedler whether California could ban imports from Mexico or Canada on the basis that products were made in a factory that failed to comply with U.S. environmental laws. Kneedler responded that such a ban would raise concerns under the foreign commerce clause.

When Solicitor General of California Michael Mongan ascended to the podium, Justice Clarence Thomas asked “how far” a state’s objection might be permissibly imposed.

“Could it extend to a state that has different political views?” Thomas suggested.

Kagan remarked that a lot of policy disputes could be incorporated into legislation like Proposition 12, and asked, “Do we want to live in a world where we are constantly at each other’s throats?”

Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked Mongan about the possible limits of a ruling in favor of California, such as whether a state could ban products produced by a company with disfavored policies such as requiring employee vaccination or prohibiting gender-affirming surgery.

Alito asked Mongan whether California is just “bullying” smaller states with its regulation in a way that would be impossible for smaller states.

“Why isn’t [Proposition 12] the same as a law that says you can’t bring products in if you’ve been produced by employees that couldn’t join a union?” Alito asked.

The Supreme Court’s inquiries about moral objections continued as attorney Jeffrey Lamken argued on behalf of the Humane Society of the United States. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Jackson each pressed Lamken on the role of morality in state production regulations.

Lamken argued that the long history and tradition of religious and moral objection to consuming animal products produced in inhumane conditions favors upholding California’s regulation. Further, Lamken pointed out, legitimate health and safety concerns are at stake given that gestation crates have been linked to higher salmonella and stress rates, as well as increased need for antibiotics.

[Image via Alex Wong/Getty Images]