Conservative Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas wants federal law enforcement agents to have something like absolute immunity from civil rights lawsuits. In a Tuesday decision, the conservative Supreme Court majority allowed Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents to shoot and kill innocent people with no recourse for the surviving family members.

In a case stylized as Hernández v. Mesa, U.S. Border Patrol Agent Jesus Mesa, Jr., shot and killed 15-year-old Mexican national Sergio Adrián Hernández Güereca while he was either playing a game (according to his family) or backtracking from a failed immigration attempt (according to the government). Hernández was on Mexican soil when he was shot in the face and killed. Mesa fired at the boy while he was on U.S. soil.

Hernández’s family sued the U.S. government seeking redress and damages for the untimely death of their child. The high court’s conservatives decided that was not to be.

The boy’s family sued using the right of action known as a Bivens claim—the only remedy for suing a federal agent who deprives someone of their constitutional rights. A Bivens claim is functionally similar to a § 1983 civil rights claim with one major exception that’s relevant for our purposes here: § 1983 claims are enshrined in statute while Bivens claims result from a long-eroded Supreme Court decision.

In 1971, Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents was decided on the basis that Federal Bureau of Narcotics agents violated the Fourth Amendment rights of Webster Bivens by entering his home, searching it and then arresting him without a warrant. The high court threw down the gauntlet against this fairly common and illegal law enforcement practice—not only tossing the drug charges but allowing Bivens to sue for redress and damages by finding an implied right because the right violated by federal agents was so important and sacrosanct under the Bill of Rights and the U.S. Constitution.

Since then, however, conservatives have attempted to claw back the rights established by the Bivens decision. Tuesday’s decision is another example.

The court’s conservatives don’t want people to be able to hold the government accountable for these sorts of things—and the court’s liberals have long had little more than just an abiding patience for the ruling. While conservative majorities have long held animus for Bivens—and have actively and successfully chipped away at the rights once afforded against federal tyranny—the liberal minority has declined to extend the landmark ruling as well.

Broadly, the ruling in Hernández v. Mesa was predictable and predicted. The conservative justices declined to extend Bivens for the umpteenth time and the liberals offered a tepid defense.

“If I said that CPB shot a child and the family was seeking damages, every non-lawyer would think ‘of course’. The court says no,” Current Affairs Legal Editor and Lawyers for Civil Rights Staff Attorney Oren Nimni noted. “Doctrinally it’s unsurprising what the court has done to Bivens, but as a human matter officer immunities plus the death gasps of Bivens are disturbing.”

Thomas, joined by fellow conservative Justice Neil Gorsuch, took things a bit further. Instead of merely declining to extend Bivens, he authored a brief concurrence advising the nation’s high court to make the entire Bivens family of rulings disappear.

”The Court correctly applies our precedents to conclude that the implied cause of action created in Bivens v. Six Unknown Fed. Narcotics Agents, 403 U. S. 388 (1971), should not be extended to cross-border shootings,” the controversial justice begins. “I therefore join its opinion.”

Then comes the kicker:

I write separately because, in my view, the time has come to consider discarding the Bivens doctrine altogether. The foundation for Bivens—the practice of creating implied causes of action in the statutory context—has already been abandoned. And the Court has consistently refused to extend the Bivens doctrine for nearly 40 years, even going so far as to suggest that Bivens and its progeny were wrongly decided. Stare decisis provides no “veneer of respectability to our continued application of [these] demonstrably incorrect precedents.” To ensure that we are not “perpetuat[ing] a usurpation of the legislative power,” we should reevaluate our continued recognition of even a limited form of the Bivens doctrine. “‘Bivens is a relic of the heady days in which this Court assumed common-law powers to create causes of action.’”

“The analysis underlying Bivens cannot be defended,” Thomas continues. “We have cabined the doctrine’s scope, undermined its foundation, and limited its precedential value. It is time to correct this Court’s error and abandon the doctrine altogether.”

The practical effect of discarding Bivens altogether, of course, is that there would be no mechanism for aggrieved parties to sue bad actor federal agents for violation of their constitutional and civil rights. The conceit, however, is Thomas and the court’s conservatives acting out of concern about the “usurpation of legislative power” by judges who make law from the bench.

University of Iowa Law Professor Andy Grewal offered a typical originalist defense.

“Is this really a ‘refusal,’ or an acknowledgement that causes of action generally arise through congressional enactments?” Grewal asked.

Legal journalist Cristian Farias answered separately: “Obviously Congress disagrees, having never disturbed Bivens.”

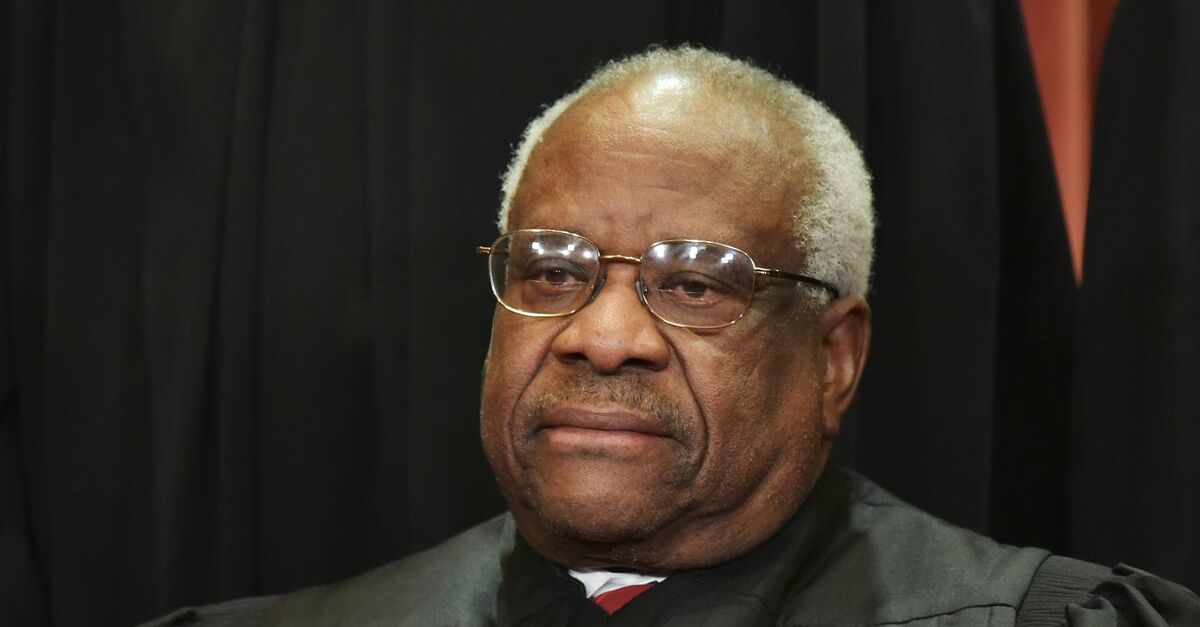

[image via Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images]