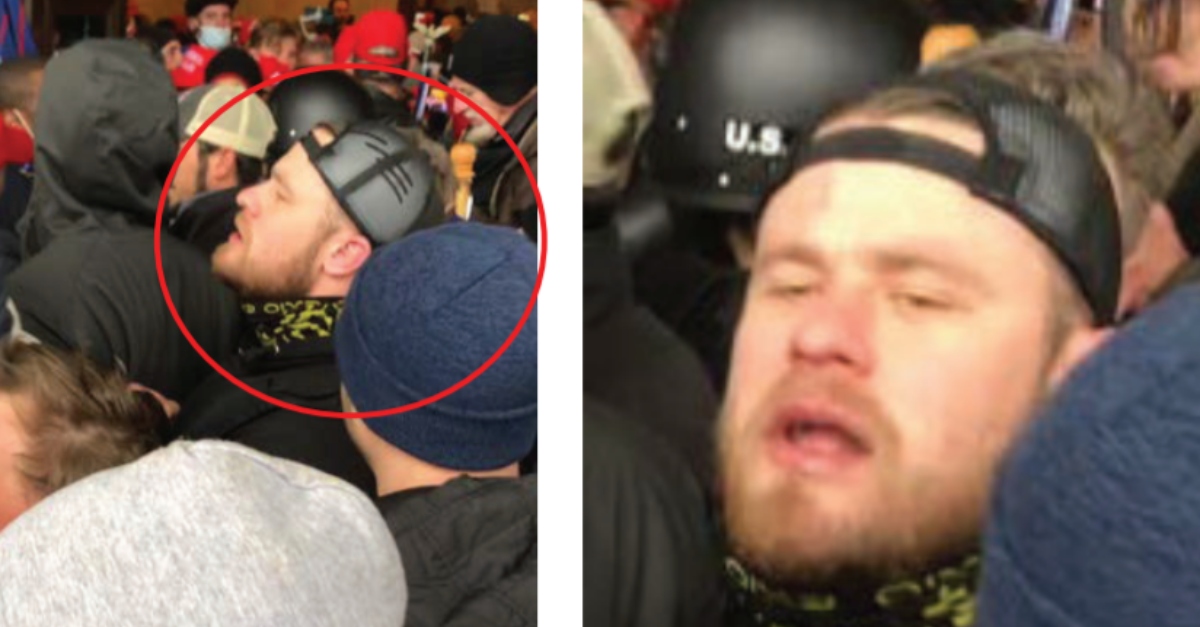

Image via FBI

A third federal judge has rejected an effort by Jan. 6 defendants to get a federal obstruction charge dismissed.

U.S. District Judge Timothy Kelly, a Donald Trump appointee, denied a motion to dismiss from four defendants: Ethan Nordean, Joseph R. Biggs, Zachary Reh, and Charles Donohoe. They are all accused of holding leadership positions or planning roles with the right-wing extremist “Proud Boys” group and allegedly conspired and coordinated their Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol.

The defendants were among the scores of Trump supporters who overran police at the Capitol building on Jan. 6 in an attempt to stop the Electoral College certification of Joe Biden‘s win in the 2020 presidential election.

Judge Kelly rejected the defendants’ claims that they should not have been charged under a federal corruption statute. That law, 18 U.S.C. 1512(c)(2), reads as follows:

(c) Whoever corruptly —

(1) alters, destroys, mutilates, or conceals a record, document, or other object, or attempts to do so, with the intent to impair the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding; or

(2) otherwise obstructs, influences, or impedes any official proceeding, or attempts to do so,

shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

Like other Jan. 6 defendants, Nordean and his co-defendants argued that the Electoral College certification the presidential election was not an “official proceeding” for purposes of the statute because “it did not involve “Congress’s implied power of investigation in aid of legislation but instead formalized the result of the 2020 U.S. Presidential election.”

Kelly wrote that he was “not persuaded” by such arguments.

“According to the Electoral Count Act of 1887, a Joint Session of the Senate and House of Representatives must convene at ‘the hour of 1 o’clock in the afternoon’ on ‘the sixth day of January succeeding every meeting of the electors,'” Kelly wrote.

He then went through all the steps the joint session of Congress must follow:

“[T]he President of the Senate (the Vice President) must open the votes, hand them to two tellers from each House, ensure the votes are properly counted, and then call for written objections, which must be signed ‘by at least one Senator and one Member of the House of Representatives.’ Once any objections are “received and read,” they must be ‘submitted’ to both the Senate and the House of Representatives for their decision. Id. ‘When the two Houses separate to decide upon an objection . . . each Senator and Representative may speak to such objection or question five minutes, and not more than once.’ The presiding officer must end the debate after two hours. The Senate and House ‘concurrently may reject the vote or votes when they agree that such vote or votes have not been so regularly given by electors whose appointment has been so certified.’ In sum, that the certification of the Electoral College vote consists of these ‘series of actions’ strongly suggests that is a ‘proceeding’ under the statute.”

The defendants also argued that 1512(c)(2) was limited by the preceding section, 1512(c)(1), which prohibits “corruptly alter[ing], destroy[ing], multilat[ing] or conceal[ing] a record, document, or other object, or attempt[ing] to do so, with the intent to impair the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding.”

Kelly, after a painstaking analysis of the statute’s wording, grammar, and punctuation, came to the opposite conclusion.

“The use of the word ‘otherwise’ suggests that Section 1512(c)(2) was intended to target something different that (c)(1) — that is, conduct ‘beyond simple document destruction,'” Kelly said in his opinion.

Kelly also rejected the defendants’ arguments that the word “corruptly” is unconstitutionally vague.

Again turning to statutory construction, Kelly noted that “‘corruptly’ in Section 1512(c) modifies two sets of open-ended verbs: ‘alter, destroy, mutilate, or conceal’ and ‘obstruct, influence, or impede,'” Kelly wrote. “Under this structure, the focus of ‘corruptly’ is how a defendant acts, not how he causes another person to act.”

Under that definition, Kelly wrote that he has “little problem finding that the use of the word ‘corruptly’ does not render Section 1512(c)(2) unconstitutionally vague as applied to Defendants, whose alleged conduct involved helping to plan and orchestrate the attack on the Capitol.”

Defendants ‘Lost Whatever First Amendment Protection’ They May Have Had

Nordean and the other defendants had argued that their conduct at the Capitol on Jan. 6 was — and is — protected by their First Amendment right to free speech.

“It is not,” Kelly wrote. “Defendants are alleged to have ‘corruptly’ obstructed, influenced, and impeded an official proceeding, and aided and abetted others to do the same . . . and succeeded in doing so.” Kelly also noted that the defendants are charged with trespass, depredation of property, and interfering with law enforcement — all with the intention of obstructing Congress’s performance of its constitutional duties.

“No matter Defendants political motivations or any political message they wished to express, this alleged conduct is simply not protected by the First Amendment,” Kelly wrote. “Defendants are not, as they argue, charged with anything like burning flags, wearing black armbands, or participating in mere sit-ins or protests. Moreover, even if the charged conduct had some expressive aspect, it lost whatever First Amendment protection it may have had.”

Kelly said that the corruption statute is “unrelated to the suppression of free expression,” and that the defendants could have chosen other ways to express their political beliefs.

“Quite obviously, there were many avenues for Defendants to express their opinions about the 2020 presidential election, or their views about how Congress should perform its constitutional duties on January 6, without resorting to the conduct with which they have been charged,” Kelly wrote.

Three Judges Agree: 1512(c)(2) Charges Remain Valid

In denying the motion to dismiss, Kelly becomes the third judge to reject efforts to toss charges under the obstruction statute.

U.S. District Judge Dabney Friedrich, also a Trump appointee, recently rejected similar arguments as to whether the Electoral College certification was an official proceeding and whether the term “corruptly” was unconstitutionally vague. In that ruling, Friedrich indicated that the analysis of whether a defendant corruptly attempted to stop the count is fact-specific and can change from case to case.

U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta, a Barack Obama appointee, also denied a motion to dismiss from Thomas Caldwell, a member of the far-right “Oath Keeper” extremist group, on similar grounds, and referred to Friedrich’s ruling in his own.

“The court has not specifically cited in this opinion to Judge Friedrich’s decision in United States v. Sandlin, which rejects many of the same arguments that Defendants make here,” Mehta wrote in a footnote. “Instead of citing to Sandlin, the court simply notes its agreement with Judge Friedrich’s holdings and finds her reasoning for those holdings to be persuasive.”

Despite those losses, other Jan. 6 defendants appear keen on raising defenses surrounding the wording of the statute.

U.S. District Judge Randolph Moss, another Obama appointee, has yet to rule on a motion to dismiss yet another U.S. Capitol Siege case on similar grounds.

Read Kelly’s decision below.

[Images via FBI.]