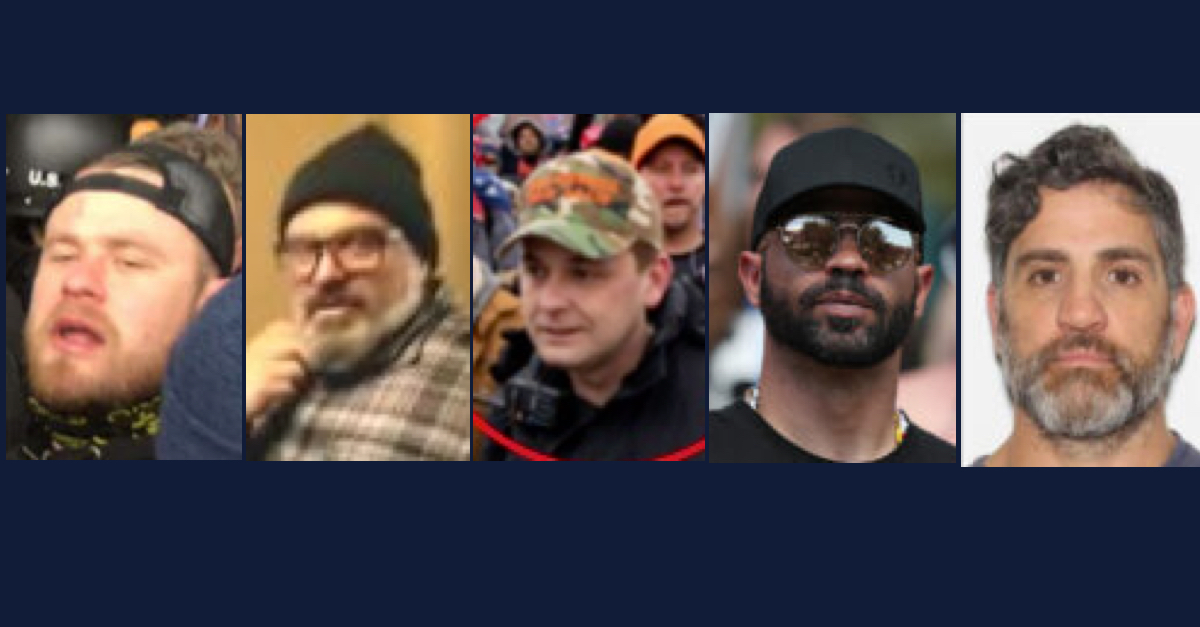

Left to right: Ethan Nordean, Joseph Biggs, Zachary Rehl, Enrique Tarrio, Dominic Pezzola, defendants in the Proud Boys Jan. 6 conspiracy case (images via FBI court filings).

Lawyers for members of the right-wing extremist Proud Boys group charged with conspiracy in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol told a federal judge that they are facing an overwhelming amount of discovery as the trial date draws closer—and that prosecutors are being deliberately difficult.

It’s not the first time the issue of discovery has come up in the trial of Proud Boys members Ethan Nordean, Joseph Biggs, Zachary Rehl, and Dominic Pezzola, who are facing charges of conspiracy, obstruction of Congress, obstruction of law enforcement, destruction of government property, and assaulting, resisting, or impeding law enforcement in connection with the Capitol riot. Pezzola faces an additional charge of robbery of U.S. property.

A sixth defendant, Charles Donohoe, pleaded guilty in April to assaulting law enforcement and is “fully” cooperating with investigators.

The lawyers raised similar concerns earlier this month.

With an Aug. 8 trial date looming, lawyers for the defendants say they simply cannot wade through the amount of discovery, and that the government must do more to ease the defense attorneys’ burden in order to avoid either surprise at trial or last-minute pretrial motions that would take up considerable time and court resources.

“They’re Being Very Helpful in Drowning Us in Discovery.”

“We are not going to have trial by ambush, to be very, very clear,” U.S. District Judge Timothy Kelly said at the start of a status conference Thursday.

Carmen Hernandez, who represents Rehl, said the current discovery setup is “not workable” in normal circumstances, and it’s made even more difficult by the fact that her client has been kept in custody.

She described a recent delivery of discovery from the government in the form of a 4TB hard drive.

“Let’s be clear what that means,” Hernandez said. “One terabyte is equal to 250,000 photos, or 250 movies. Or 500 hours of video. Or 6.5 million document pages. Or 1,300 physical filing cabinets of paper. That’s one terabyte. They filed a four-terabyte hard drive on Friday. That’s on top of another four-terabyte hard drive they produced a few months ago[.]”

Kelly asked Hernandez whether she believed prosecutors were being helpful during the discovery process.

“They’re being very helpful in drowning us in discovery,” she replied.

“It is physically impossible,” she continued. “I cannot work anymore hours. I think two or three hours of sleep each night is sufficient.”

Hernandez also said that the index the government provided with the hard drive is nine pages long, implying that it, too, was confusing and didn’t highlight important evidence relevant to the case.

Hernandez pointed out that she is one defense attorney trying to represent a client who is in custody, while the federal government has significantly more resources.

“I’m glad to have it, I’m glad they’re producing it,” Hernandez said of the voluminous discovery. “But there has to be some reasonable sense of priority here for me … for every AUSA working on this case, can I have 5 CJA [Criminal Justice Act] lawyers working on this case, and seven FBI agents, and [paralegals]?”

The Justice Department’s pursuit of the perpetrators is indeed expansive: so far, more than 810 defendants have been arrested in connection with the siege at the Capitol, and around 280 of them have pleaded guilty, according to the DOJ.

Attorney Nicholas Smith, who represents Nordean, told Kelly that the government is taking an unusually harsh approach to discovery.

“We feel like there’s a spirit of hardball discovery,” Smith said, noting that such an approach is unusual for criminal cases. “This isn’t the game. It’s important that the defense gets all the materials it needs to get.”

Smith requested that Kelly order prosecutors to place all video evidence on a cloud-based website in order to make sure that the defense lawyers had all the material they needed. Kelly said he wouldn’t make such an order at this time, but encouraged the parties to try to come to an agreement.

“The Fact That They’re Not Telling Me Is Telling Me It’s Really Important.”

Prosecutors told Kelly that the government has made a “good faith effort” to provide discovery and highlight the most relevant portions in order to prevent surprise at trial.

“Neither Mr. Rehl nor any other defendant in this case is in the dark or left to speculate what the government’s case against them is going to look like,” trial attorney Conor Mulroe told Kelly.

Hernandez said that she has been unable to identify one particularly important piece of information: the person who sent the document identified as “1776 Returns” to Tarrio. That document, according to prosecutors, “set forth a plan to occupy a few ‘crucial buildings’ in Washington, D.C., on January 6, including House and Senate office buildings around the Capitol, with as ‘many people as possible’ to ‘show our politicians We the People are in charge.’”

Prosecutors say that after sending the document, the sender, whose identity is known to the grand jury, said: “The revolution is important than anything.”

“That’s what every waking moment consists of… I’m not playing games,” Tarrio allegedly replied.

Hernandez said that she believed prosecutors are hiding the identity of the person who sent that document from her.

“The fact that they’re not telling me is telling me it’s really important,” she said.

Mulroe, the prosecutor, said that Hernandez has information from Tarrio’s phone.

“Mr. Tarrio’s phone has been produced in the discovery materials,” he said. “She’s got the phone that Tarrio used to receive that particular document and to discuss it with the person it came from.”

“I have the phone,” Hernandez shot back. “I spent hours looking for this kernel of information. I asked for someone with more computer knowledge than myself to help navigate this extraction. I found the document itself but I was unable to find who sent it. I don’t understand how it makes any sense—I should spend hours and hours on videos that are repeats of other information but I can’t get this one piece of information.”

At this, Kelly told the government that it needed to be more forthcoming with the information.

“I think it’s incumbent on the government when she says ‘I’m looking for a particular document here, can you help me locate it’—if it doesn’t exist it doesn’t exist, but if a document does exist and you all know and she’s trying to identify it, it seems to me that it will save … a lot of time and effort in having to respond to Brady motions[.]”

Kelly told prosecutors to help Hernandez to “navigate the discovery,” acknowledging that it while “in some ways that is above and beyond what the [discovery] rule technically requires,” this particular situation calls for the parties to work together.

“We’re not going to have a trial by ambush here,” he said again.

[Images via FBI court filings.]