In the waning days of Donald Trump‘s presidency, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) identified specific threats ahead of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol but didn’t share that intelligence until days after the violent siege, according to a government watchdog report.

The DHS Office of Inspector General released its report Tuesday more than a year after it launched its investigation into the “role and activity” of the department’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) “in preparing for and responding to the events at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021.”

On that day, hundreds of Trump supporters overran the police and violently broke into the Capitol building in an effort to stop Congress from certifying Joe Biden‘s win in the 2020 presidential election.

Homeland Security, according to the OIG report, had specific intelligence relating to what would eventually come to pass on Jan. 6 but didn’t share that information until two days afterwards.

“I&A identified specific threat information related to the events on January 6, 2021, but did not issue any intelligence products about these threats until January 8, 2021,” the OIG report says.

According to the report’s findings:

Open source collectors in I&A’s Current and Emerging Threats Center collected open source threat information but did not produce any actionable information. Collectors also described hesitancy following scrutiny of I&A’s reporting in response to civil unrest in the summer of 2020. Although an open source collector submitted one product for review on January 5, 2021, I&A did not distribute the product until 2 days after the events at the U.S. Capitol. Additionally, I&A’s Counterterrorism Mission Center (CTMC) identified indicators that the January 6, 2021 events might turn violent but did not issue an intelligence product outside I&A, even though it had done so for other events. Instead, CTMC identified these threat indicators for an internal I&A leadership briefing, only. Finally, the Field Operations Division (FOD) considered issuing intelligence products on at least three occasions prior to January 6, 2021, but FOD did not disseminate any such products ultimately. It is unclear why FOD failed to disseminate these products.

According to the report, even when threat information was sent to “local partners” via email, that information was “not as widely disseminated as I&A’s typical intelligence products,” resulting in I&A being “unable to provide its many state, local, and Federal partners with timely, actionable, and predictive intelligence.”

In a partially-redacted segment of the report, the OIG details the difference in leadership at I&A in the summer of 2020 and in January 2021. In connection with unrest in Portland related to ongoing protests and demonstrations over racial injustice sparked by the since-proven murder of George Floyd by former police officer Derek Chauvin, I&A “faced criticism for compiling intelligence on American journalists reporting on the unrest as well as on non-violent protesters.”

The result, according to the OIG report, was a change in policy at the department, setting a much higher bar for sharing intelligence information.

When we asked the Acting Deputy Under Secretary about the change in CETC’s approach to reporting, she noted that there was different leadership for the summer of 2020 compared to January 6, 2021. She said the prior leadership pushed collectors to report on anything related to violence, including potential threats or tactics and techniques used by individuals that may be associated with violence. In contrast, the new leadership encouraged collectors to issue intelligence reports on threats only when they were confident the threats were real. The Acting Deputy Under Secretary said this change in direction went too far and caused collectors to institute a very high threshold for reporting information.

In one instance, an investigator had collected information “about an individual arriving in the Washington, D.C. area and searching for a location for armed individuals to park their cars,” the report said. “The individual previously posted online that he would arrive in the area and he was Washington, D.C.”

However, a peer reviewer said that collector’s report didn’t meet the department’s reporting thresholds. The investigator apparently sought to disseminate the information by going up the chain of command, but by the time they had permission to do so — on Jan. 8 — it was too late.

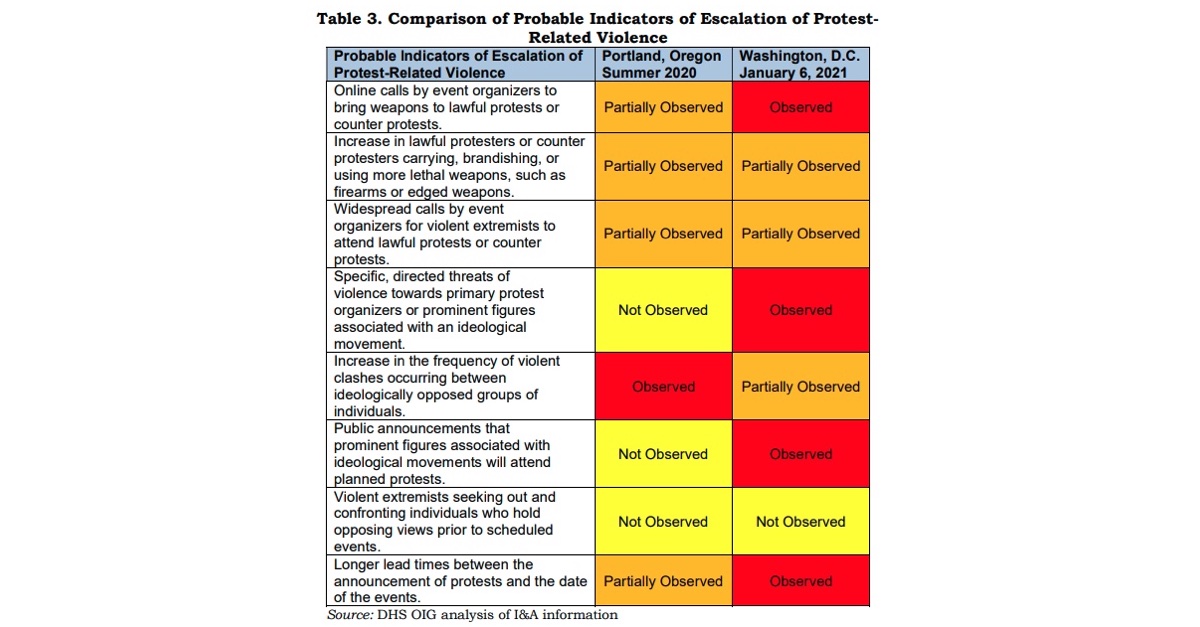

In another example, analysis about “seven observed or partially observed indicators of potential violence associated specifically with the protests planned for Jan. 6” was used in an internal briefing only, and not shared with other departments.

In one illustrative chart, the OIG report compares indicators of possible protest-related violence from the summer of 2020 in Portland, Oregon, to indicators ahead of Jan. 6. Although investigators identified seven indicators ahead of the violence in Washington—compared to five indicators related to Portland—the Jan. 6 analysis wasn’t disseminated.

As a result of the report, the OIG recommend enhanced training and other processes to improve timeliness

Read the OIG report here.

[Image via YouTube screengrab.]