Former U.S. President Donald Trump arrives at a rally on April 23, 2022 in Delaware, Ohio. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images.)

Calling an FBI search of Mar-a-Lago an “unprecedented, unnecessary, and legally unsupported raid,” a group of three attorneys for former President Donald Trump on Wednesday filed court papers which argued that the government was engaged in an “unjustified pursuit of criminalizing a former President’s possession of personal and Presidential records in a secure setting.”

The 19-page reply was a response to a late Tuesday filing by the U.S. Department of Justice in a matter stylized as Trump v. United States. That DOJ asserted that FBI agents recovered secret and classified documents from a personal office at the palatial Mar-a-Lago home and club in Palm Beach, Florida, and from a secured room.

The Aug. 8 search has been the subject of significant litigation before a magistrate judge. Rather than challenge the warrant head-on before the magistrate who approved it, Trump’s lawyers filed a parallel case to request, among other things, a “special master” review of the material for potential privilege. The DOJ said privileged materials were ferreted out by a separate screening process and that no “special master” was necessary.

Some of the documents recovered were so deeply classified that the federal prosecutors tapped to handle the matter had to seek additional security clearances to handle the case, the DOJ asserted in its Tuesday filing.

Former U.S. President Donald Trump’s residence at Mar-A-Lago, in Palm Beach, Florida, was photographed on August 9, 2022. (Photo by Giorgio Viera/AFP via Getty Images.)

Trump’s lawyers — Lindsay Halligan of Fort Lauderdale, James M. Trusty of Washington, D.C., and M. Evan Corcoran of Baltimore — complained on Wednesday that the DOJ had “significantly mischaracterized” the facts of the matter.

“If the Government provided the same untrue account in the affidavit in support of the search warrant, then they misled the Magistrate Judge,” the document quips.

The Trump legal team accused the DOJ of concocting a “convoluted theory” about executive privilege. That theory, when paraphrased by Trump’s legal team, “appears to be that the Biden administration will not allow President Trump to assert executive privilege” over the documents seized because Trump “has ‘no right’ to possess Presidential documents, and that, therefore, he has no standing to object to their seizure.”

That theory, the lawyers claimed, “is contrary to the well-established doctrine of standing.”

“It is the reasonable expectation of privacy in one’s home that triggers the obvious standing of the homeowner to contest a search on those premises,” Trump’s lawyers argued in one of several passages that conjured the nebulous notion that the documents were Trump’s to keep.

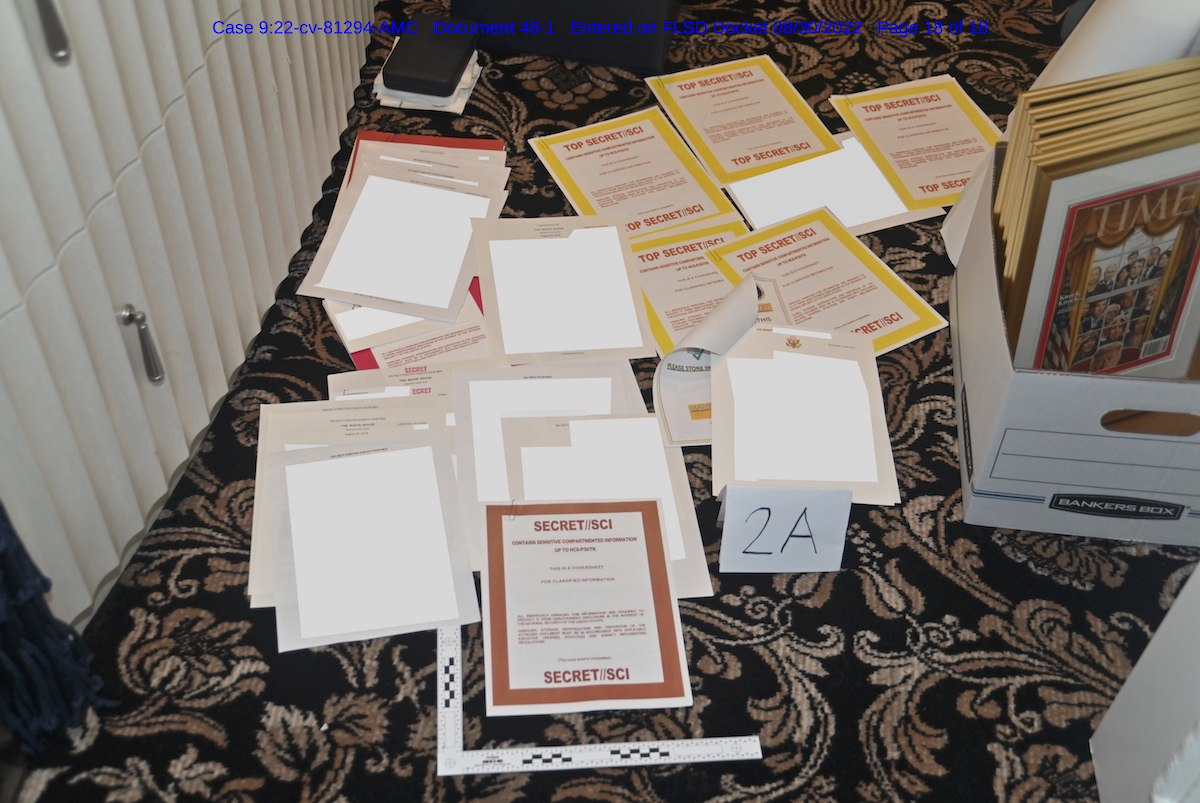

Federal prosecutors say FBI agents seized these materials from Mar-a-Lago. The contents of the documents were redacted with white squares. (Image via an Aug. 31, 2022 federal court filing.)

Wednesday’s response filing then centers on the applicable laws at play. The government has long suggested that it was investigating potential violations of 18 U.S.C. §§ 793, 2071, and 1519 — a series of statutes again cited by the Trump team but characterized as an incomplete picture of the applicable law. Rather, Trump’s lawyers offered that the dispute should center on another law, the Presidential Records Act, which is a concept they have floated in past documents as well:

Indeed, the warrant intentionally blurs important distinctions in referring to the ability of FBI agents to seize “Presidential Records” (the PRA never concerns itself with traditional classification labels) while wrongfully suggesting the applicability of the Espionage Act and referring to expectations of recovering classified or highly classified documents. For the moment, counsel for Movant can only speculate on how the affidavit in support of the search warrant characterized the Government’s intended escape from the PRA paradigm. What is also noteworthy here is that, as admitted in the Response, just weeks after President Trump voluntarily complied with a National Archives and Records Administration (“NARA”) request for Presidential records and turned over 15 boxes, NARA simply ignored the PRA and initiated a criminal investigation. The purported justification for the initiation of this criminal probe was the alleged discovery of sensitive information contained within the 15 boxes of Presidential records. But this “discovery” was to be fully anticipated given the very nature of Presidential records. Simply put, the notion that Presidential records would contain sensitive information should have never been cause for alarm. Rather, as contemplated under the PRA, NARA should have simply followed up with Movant in a good faith effort to secure the recovery of the Presidential records.

The DOJ on Tuesday said Trump associates stymied multiple government attempts to recover the documents, which the DOJ asserts are government property.

Trump’s attorneys on Wednesday, however, countered that the PRA gave Trump “broad parameters . . . to possess” the documents in dispute, notwithstanding the laws cited by the DOJ as the gravamen of the instant action.

Trump’s attorneys also said the government’s failure to articulate a PRA analysis showed signs of “clear desperation.”

Ensuing pages of the reply document argued that (1) Trump has standing to seek a special master at this particular time and in this particular fashion; (2) that the court has “equitable jurisdiction” to appoint a special master; and (3) that the court should, indeed, make the proffered appointment — a move Trump’s attorneys called a “modest step.”

Among the ensuing arguments, Trump’s lawyers revealed a litigation strategy: Trump “intends to challenge” the documents “as seized in violation of the Fourth Amendment and the Presidential Records Act and thus subject to return (to the Movant or to his designee) under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41(g).”

They further posited that the government had thumbed its nose a suggestion that U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon was erring toward, rather than against, a special master appointment. Rather than stand down and wait for Judge Cannon to settle the matter, Trump’s lawyers elucidated that the government had admitted, “in a moment of astonishing efficiency,” that it had assembled a “filter team” to begin segregating privileged material. Then, per Trump’s attorneys, the government admitted that it began sharing so-called “non-privileged” material with an “investigative team” and that it was also “currently facilitating” a classification review by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (“ODNI”).

The thought that the government wanted to read government documents — or, as Trump’s supporters might argue, that functionaries within the Biden administration would want to read the Trump Administration’s secret documents — seems to have infuriated Trump and/or his lawyers. They have, as of this filing, told Judge Cannon that they want the material back and will fight for its return.

The alternative, they hypothesized, would be something akin to ghastly.

“Left unchecked, the DOJ will impugn, leak, and publicize selective aspects of their investigation with no recourse for Movant but to somehow trust the self-restraint of currently unchecked investigators,” Trump’s attorneys wrote.

Again, here, they indicated that they want the material in question to remain secret — and in the hands of a special master, Trump’s counsel, or Trump himself.

“While DOJ may have succeeded in taking a partial filter to their rummaged proceeds, the need for a Special Master remains in place,” the Trump attorneys argued. “Assuring access by Movant’s counsel to the seized materials, sharing an actual (detailed) inventory, making independent attorney-client privilege assessments, and making executive privilege determinations are all responsibilities that are best served by appointment of a Special Master.”

In one additional passage, Trump’s attorneys quibbled with an alleged lack of specifics about where some of the items were recovered at Mar-a-Lago (some punctuation and citations omitted):

[T]he Government indicated that there were “three classified documents . . . located in the desks in the 45 Office.” The Government also noted that [Trump’s] passports were seized along with the contents of a desk drawer, without stating where the desk was located. The only other indication the Government offers as to where the Seized Materials came from is the statement that, “in the storage room alone, FBI agents found 76 documents bearing classification markings.” Accordingly, there is no guarantee that the “limited set” of potentially privileged materials identified by the Privilege Review Team constitutes all privileged materials among the Seized Materials.

The bulk of the document then contains specific suggestions as to the special master’s duties — if one is appointed.

Though Trump has claimed on social media that he “declassified” the documents at issue, the filing nowhere contains that assertion — let alone that word. Rather, something akin to the contrary is asserted: “Movant also agrees that it would be appropriate for the special master to possess a Top Secret/SCI security clearance.”

Near its conclusion, the filing slammed the DOJ for filing a redacted photo of some of the documents it recovered. That image, Trump’s lawyers said, was a “gratuitously included a photograph of allegedly classified materials, pulled from a container and spread across the floor for dramatic effect.”

The document ends with one of several embedded complaints of alleged politicization within the DOJ.

The Twitterverse quickly criticized the filing as part of a “PR” stunt.

Attorney Sara Azari referred to the document as “a string of lies, misconstrued legal principles and irrelevant assertions for the greater purpose of PR.”

Trump’s reply is a string of lies, misconstrued legal principles and irrelevant assertions for the greater purpose of PR. https://t.co/Ol7OYUgL60

— Sara Azari (@azarilaw) September 1, 2022

Los Angeles Times legal affairs columnist Harry Litman correctly noted a key distinction that Trump’s attorneys smudged: while charged criminal defendants can challenge search warrants, uncharged parties usually struggle significantly in efforts to do so.

A few overview points on the Trump filing, which is deeply muddled and flailing:

1. The attempted response to DOJ position that he has no standing b/c he has no right to possess the documents is w/ cases in which people have been charged criminally so of course they have standing— Harry Litman (@harrylitman) September 1, 2022

a. in general, a criminal defendant can challenge anything about a search but an uncharged person can only bring a civil action against officers and w/ huge procedural obstacles. he hasn’t done that.

b. the cases he cites are US v ____, US v ____. ie they involve charged defts— Harry Litman (@harrylitman) September 1, 2022

Law professor Jennifer Taub, for her part, called the filing “cringeworthy.”

The entire filing, which is peppered with assertions that the government is in “haste to avoid judicial oversight,” is below: