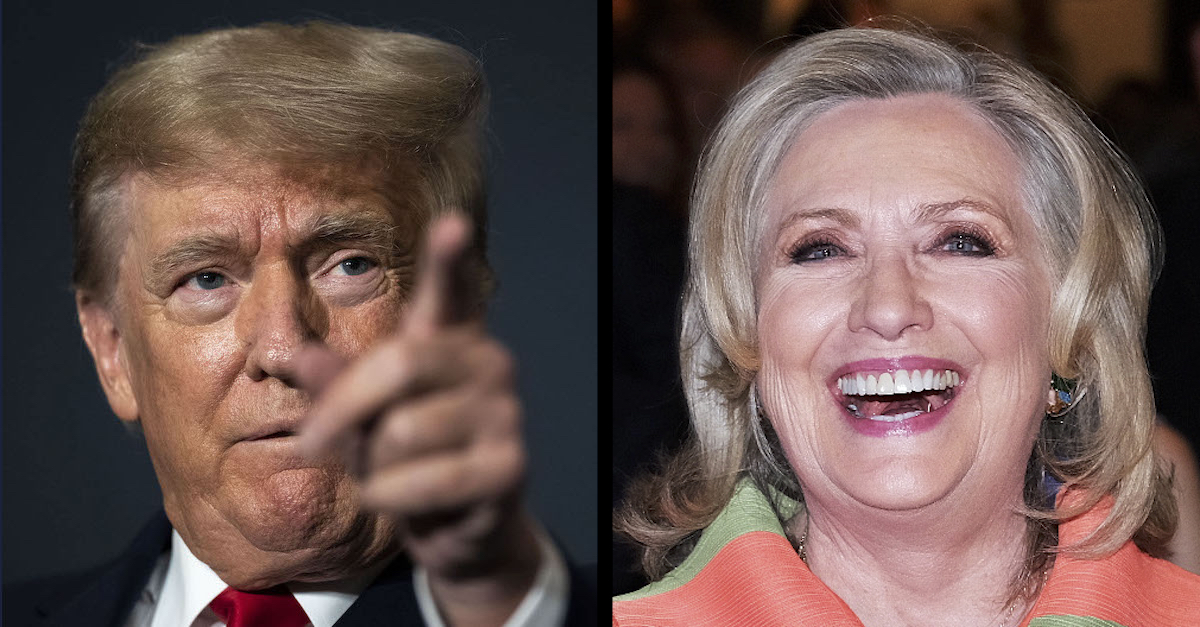

Donald Trump was photographed July 26 in Washington, D.C. Hillary Clinton was seen Sept. 1, 2022 in Venice, Italy.

The federal judge who dismissed Donald Trump’s $24 million racketeering lawsuit against Hillary Clinton and many others penned several third-degree judicial burns while tossing the case.

Here are the top 13 benchslaps U.S. District Judge Donald M. Middlebrooks dished out in the opinion and order that threw out the sprawling litigation — which the judge at one point referred to as a “two-hundred-page political manifesto.”

(1) The Rules of Civil Procedure require complaints to contain a “short and plain statement” of the grievance alleged.

However, from the judge:

Plaintiff’s theory of this case, set forth over 527 paragraphs in the first 118 pages of the Amended Complaint, is difficult to summarize in a concise and cohesive manner. It was certainly not presented that way.

As if to school Trump’s attorneys, the judge then suggested “[t]he short version” of the case — in one paragraph.

Later, the judge revisited the matter:

Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint is 193 pages in length, with 819 numbered paragraphs. It contains 14 counts, names 31 defendants, 10 “John Does” described as fictitious and unknown persons, and 10 “ABC Corporations” identified as fictitious and unknown entities. Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint is neither short nor plain, and it certainly does not establish that Plaintiff is entitled to any relief.

And again:

Plaintiff has annotated the Amended Complaint with 293 footnotes containing references to various public reports and findings. He is not required to annotate his Complaint; in fact, it is inconsistent with Rule 8’s requirement of a short and plain statement of the claim.

And again:

The sprawling nature of the Amended Complaint and the number of defendants makes analysis difficult to organize.

And again, this time commenting on a “mortal sin”:

To say that Plaintiff’s 193-page, 819-paragraph Amended Complaint is excessive in length would be putting things mildly. And to make matters worse, the Amended Complaint commits the “mortal sin” of incorporating by reference into every count all the general allegations and all the allegations of the preceding counts.

(2) The judge called the complaint style one of “shotgun pleading” and a “waste of judicial resources.”

As I have already alluded, Plaintiff’s pleading contains glaring structural deficiencies. I would be remiss to not expound upon these further before I set out to evaluate the substantive viability of Plaintiff’s claims.

Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint is a quintessential shotgun pleading, and “[c]ourts in the Eleventh Circuit have little tolerance for shotgun pleadings.” Vibe Micro, Inc. v. Shabanets, 878 F.3d 1291, 1295 (11th Cir. 2018). Such pleadings waste judicial resources and are an unacceptable form of establishing a claim for relief. Id.; Strategic Income Fund, LLC v. Spear, Leeds & Kellogg Corp., 305 F.3d 1293, 1295–96 & ns. 9, 10 (11th Cir. 2002).

(3) The judge quoted the defendants’ characterization of the entire case as “a fundraising tool” or a “press release.”

“I agree,” Middlebrooks wrote after citing the requisite language.

(4) The judge said the entire lawsuit should be shut down with prejudice:

“More troubling” than the verbosity of the Trump filing, the judge wrote, was that “the claims presented in the Amended Complaint are not warranted under existing law.”

Elsewhere, the judge said Trump’s RICO claims in particular “fail on the merits at every step of the analysis.”

(5) The judge said Trump’s lawyers were ignoring the law — over and over again:

Middlebrooks took several cues to school Trump’s lawyers about what the law actually says. He accused them of “ignor[ing] the Supreme Court’s holdings” about wire fraud, “fail[ing] to account for the Supreme Court’s requirement” that obstruction of justice allegations must relate to an actual judicial proceeding, and of otherwise making “implausible” arguments that “lack any specific allegations which might provide factual support for the conclusions reached.”

Elsewhere, the judge noted that Trump’s claims for “malicious prosecution” were rubbish: “Plaintiff was never prosecuted.”

The error-of-law train of thought continued in the document as to personal jurisdiction:

Plaintiff misunderstands the applicable law with respect to the constitutional exercise of personal jurisdiction over non-resident defendants, which render Plaintiff’s allegations insufficient for the exercise of personal jurisdiction over Defendants Dolan, Joffe, and Orbis.

The personal jurisdiction analysis included a snarky hypothetical to make the point that Trump’s lawyers were pressing a failing argument:

Here, Plaintiff has not alleged that Defendants “aimed” any conduct at Florida or could reasonably have anticipated that Plaintiff would be harmed in Florida, particularly in light of the fact that Plaintiff was a resident of New York at the time of the occurrences giving rise to Plaintiff’s claims. Knowledge that Florida is a state in the United States does not equate to knowledge that Defendants’ actions will have consequences in Florida. If that were the case, there would be nationwide personal jurisdiction over almost all claims arising in the United States. Such is clearly not contemplated by Florida’s long-arm statute, and I therefore reject Plaintiff’s argument.

Elsewhere, the judge said that the “Plaintiff misunderstands the law” with regards to how to calculate a statute of limitations assessment.

During an analysis of Trump’s RICO claims, the judge — again — said Trump’s lawyers were not accurately describing the law.

“But that is not what the statute says, and Plaintiff may not misconstrue it in this way,” Middlebrooks said in a refrain after citing and quoting Trump’s legal arguments.

Additionally, in an analysis of whether the transmission of the alleged DNS activity of Trump-affiliated internet servers was the theft of a trade secret or some sort of wire fraud, Middlebrooks ruled that it was not.

“DNS data is meant to be public,” the judge wrote while rubbishing the notion that the material was somehow secret or private. “Plaintiff has not alleged facts that bring the DNS internet traffic at issue within the statutory definition of a ‘trade secret.'”

Trade secrets involve economic value, the judge wrote. Here, however, at best, Trump laid out claims that his DNS activity had “political value” — “this does not suffice to plausibly allege a trade secret, which must derive economic value from nondisclosure.”

A similar failure occurred as to RICO law, the judge ruled. Here, the alleged harms to Trump’s business were not sufficiently connected by his lawyers to the alleged conduct of the defendants, according to the judge.

Missing from the Amended Complaint . . . is any allegation directly connecting Defendants’ conduct to any of these harms. Plaintiff has not alleged facts of any specific business opportunities, revenue, or goodwill lost because of Defendants’ actions. Without any such allegations, Plaintiff has not, and cannot, show that any of these harms were the direct result of any racketeering activity. For this reason, I agree that Plaintiff has failed to allege facts that establish RICO standing.

(6) The judge said Trump’s lawyers were mischaracterizing their own cited materials:

This complaint was a frequent refrain from the judge.

“[I]f a party chooses to include such references, it is expected that they be presented in good faith and with evidentiary support,” he wrote in one instance. “Unfortunately, that is not the case here.”

A similar complaint arose with regards to an inspector general’s report cited by Trump’s lawyers.

“I went to page 96 of the Inspector General’s Report looking for support for Plaintiff’s conclusory and argumentative statement but found none,” the judge wrote — here citing the precise page referenced by Team Trump.

Indeed, after the judge checked the IG report as a whole, he determined that it reached an entirely different conclusion — one Trump’s “Amended Complaint fails to acknowledge.”

“Plaintiff and his lawyers are of course free to reject the conclusion of the Inspector General,” Middlebrooks wrote. “But they cannot misrepresent it in a pleading.”

Elsewhere, Middlebrooks said that Trump’s lawyers chided Michael Sussmann’s indictment but failed to mention that Sussmann was acquitted.

The judge considered that error by omission to be a rather serious misstep:

In presenting a pleading, an attorney certifies that it is not being presented for any improper purpose; that the claims are warranted under the law; and that the factual contentions have evidentiary support. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 11. By filing the Amended Complaint, Plaintiff’s lawyers certified to the Court that, to the best of their knowledge, “the claims, defenses, and other legal contentions are warranted by existing law or by a nonfrivolous argument for extending, modifying, or reversing existing law or for establishing new law,” and that “the factual contentions have evidentiary support[.]” Fed. R. Civ. P. 11(b)(2). I have serious doubts about whether that standard is met here.

Indeed, the judge brought this issue up several times in several sections of the document:

Plaintiff’s heavy reliance on the Sussmann indictment throughout his Amended Complaint is curious given that Sussmann was acquitted by a unanimous jury of making a false statement to the FBI, a fact which Plaintiff fails even to acknowledge anywhere in the pleading.

Toward the end of the analysis, the judge said Trump’s lawyers “puzzlingly” cited to a case which, again, “contradicts his argument.”

(7) The judge nailed Trump’s lawyers for raising claims against “John Doe” defendants.

Here’s the judge’s explanation:

The Amended Complaint also contains impermissible fictitious-party pleading. “As a general matter, fictitious-party pleading is not permitted in federal court.” Richardson v. Johnson, 598 F.3d 734, 738 (11th Cir. 2010); Fed. R. Civ. P. 10(a) (“The title of the complaint must name all the parties.”). A limited exception exists: “when the plaintiff’s description of the defendant is so specific as to be ‘at the very worst, surplusage.’” Id. (quoting Dean v. Barber, 951 F.2d 1210, 1215–16 (11th Cir. 1992)).

Of course, here, that exception didn’t apply.

Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint does not describe the fictitious defendants with the requisite specificity to proceed against them in this fashion. He describes the John Doe defendants as “journalists, publishers, editors, investigators, state or federal officials, co-conspirators, officers, employees, agents, managers, owners, principals and/or other duly authorized individuals who caused or contributed to the incident or incidents for which the Plaintiff seeks damages[.]”

“These descriptions do nothing to specifically identify the John Doe individuals or ABC corporations,” the judge opined. “As a result, the fictitious individual and corporate defendants are dismissed without prejudice.”

(8) The judge schooled Trump’s lawyers on whether or not several of the defendants were acting in the “scope” of their employment for the government.

This issue has been hotly litigated in previous motions. Trump attempted to sue James Comey, Andrew McCabe, Peter Strzok, Lisa Page, Kevin Clinesmith, Bruce Ohr, Rod Rosenstein, and Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif. 28) individually over acts the various defendants, the U.S. Government, and Judge Middlebrooks agreed were part of their “employment” or service with the government.

Namely, Trump’s allegations surrounded Schiff’s statements to the press, and “[s]peaking to the press about public policy concerns falls within the scope of the duties of a member of Congress,” the judge noted (while citing five other cases as examples of that legal doctrine).

Additionally, the gravamen of Trump’s grievances against several of the others involved Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) warrants, and “counterintelligence operations and FISA surveillance are all activities of the FBI and the Department of Justice,” the judge reminded Trump’s legal team.

(9) Judge uses Trump’s tweets against Trump lawyers.

Another hotly contested portion of the case involved the four-year statute of limitations on the torts alleged by Team Trump. Trump’s lawyers claimed that the statute should be tolled — or paused — during the entire time Trump was in office. Judge Middlebrooks pointed to a case involving Bill Clinton, the president who appointed him, which said the opposite was true: civil litigation can commence while a president is in office. Plus, Middlebrooks said Trump had launched a bevy of other civil lawsuits while he was in office, making his claim that this case was different rather hypocritical.

A portion of the the statute of limitations analysis involved assertions that Trump wasn’t aware of the alleged conduct by the defendants until years after it occurred. Such arguments can sometimes successfully override the statute of limitations, but not here, the judge wrote, because of Trump’s tweets on the subject his lawyers claimed he didn’t know much or anything.

The judge then included a sampling of Trump’s tweets in the order.

“Plaintiff’s tweets appear to fall within the category of information that this Circuit has recognized as appropriate for taking judicial notice: facts that are not subject to reasonable dispute from sources whose accuracy cannot reasonably be questioned,” the judge said as to his ability to consider the tweets in the first place.

“I note, though, that even without Plaintiff’s tweets, the allegations in Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint demonstrate that Plaintiff was aware of the basis of his claims since at least 2017,” Judge Middlebrooks continued. “Although the tweets provide further support, they are not essential to my ruling on the RICO statute of limitations.”

The judge continued:

Plaintiff was aware of the factual basis underlying his RICO claims since at least October 2017, if not earlier. It is not reasonable or plausible to conclude that, despite the allegations in the Amended Complaint that numerous prominent media outlets ran stories on the theory underlying Plaintiff’s claims as early as 2016, which were shared by his political opponent in the 2016 presidential election, Plaintiff was not aware of his claims until the Sussmann indictment was returned in September 2021. And indeed, Plaintiff does not appear to meaningfully dispute that he knew of his claims since that time.

Trump’s other legal excuses for not taking swift action in the matter were then jettisoned by the judge.

“Both the Amended Complaint and Plaintiff’s tweets belie any argument that his claims should be equitably tolled,” the judge said. “Plaintiff cannot in good faith claim to have had no knowledge of a claim that he broadcasted to his social media followers nearly five years ago.”

(10) The judge said Trump’s references to the Steele Dossier failed to allege that anything in it was untrue:

Here, the judge picked the alleged facts through scattered references in the complaint. We’ve included the judge’s citations to the record to note how far-flung the allegations were in the original:

Defendant Steele, a resident of the United Kingdom, is alleged to have drafted a dossier about Plaintiff, the first report of which was furnished June 20, 2016. (Id. ¶¶ 110, 147). Defendant Steele, described in the Amended Complaint as a paid FBI informant, began sending the dossier to the FBI on July 5, 2016 (Id. ¶ 158), and September 19, 2016 (Id. ¶ 226), met with members of the news media on September 21, 2016, FBI agents and a State Department official on October 3 and October 11, 2016 (Id. ¶¶ 233-234), and a reporter for Mother Jones on October 31, 2016 (Id. ¶ 272). A copy of Defendant Steele’s dossier was then provided to Senator John McCain in early 2016, who provided a copy to Defendant FBI director Comey on December 9, 2016. (Id. ¶¶ 290, 291). Copies of the dossier were leaked to the press, and it was published in full by Buzzfeed on January 10, 2017 (Id. ¶¶ 292, 294, 295).

“Despite all of these references to Defendant Steele scattered throughout the Amended Complaint, none specifically attribute any false statement about Plaintiff to him,” the judge said.

And, besides, “[a]ll of these activities are alleged to have occurred well outside the statute of limitations for injurious falsehood.”

(11) The judge dismissed Trump’s notion that the alleged injurious falsehoods damaged Trump’s political career in 2016.

The judge repeated what Law&Crime has repeatedly noted, that Trump’s complaint involved an election which he won:

Because Plaintiff does not have a property or contract right to political office, attacks on his fitness for such a role do not constitute trade libel. And even if they did, Plaintiff does not plausibly allege that any supposed falsehoods actually damaged his political career: as Plaintiff knows, he — not Defendant Clinton — won the 2016 presidential election.

(12) The judge said the complaint was, in essence, long on legal nonsense and light on meritorious claims and contentions:

“What the Amended Complaint lacks in substance and legal support it seeks to substitute with length, hyperbole, and the settling of scores and grievances,” Middlebrooks wrote.

And therein lies the rub: the judge flatly stated that the complaint was chock full of allegedly nefarious yet legally pointless detail.

(13) The judge penned a coup de grace as to Trump’s “manifesto” masquerading as a lawsuit:

Plaintiff added eighty new pages of largely irrelevant allegations that did nothing to salvage the legal sufficiency of his claims. The inadequacies with Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint are not “merely issues of technical pleading,” as Plaintiff contends, but fatal substantive defects that preclude Plaintiff from proceeding under any of the theories he has presented. At its core, the problem with Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint is that Plaintiff is not attempting to seek redress for any legal harm; instead, he is seeking to flaunt a two-hundred-page political manifesto outlining his grievances against those that have opposed him, and this Court is not the appropriate forum.

Fundamentally, Plaintiff cannot state a RICO claim without two predicate acts, and, after two attempts, he has failed to plausibly allege even one. Plaintiff cannot state an injurious falsehood claim without allegations of harm to his property interests. And Plaintiff cannot state a malicious prosecution claim without a judicial proceeding, but he unsuccessfully attempts to misconstrue, misstate, and misapply the law to do so anyway. Moreover, Plaintiff’s statutory claims premised on the DNS data rest on a misconstruction of the conduct those laws proscribe and the harms they remediate. Because Plaintiff was unable to cure his Complaint even with all its shortcomings clearly laid out for him, and because most of Plaintiff’s claims are not only unsupported by any legal authority but plainly foreclosed by binding precedent as set forth by the Supreme Court and the Eleventh Circuit, I find that amendment would be futile and that this case should be dismissed with prejudice as to the Defendants that have raised merits arguments.

Trump’s lawyers have said they will appeal the judge’s decision to dismiss the matter.

The full order is here:

(Photo of Trump by Drew Angerer/Getty Images; photo of Clinton by Stefano Mazzola/Getty Images.)