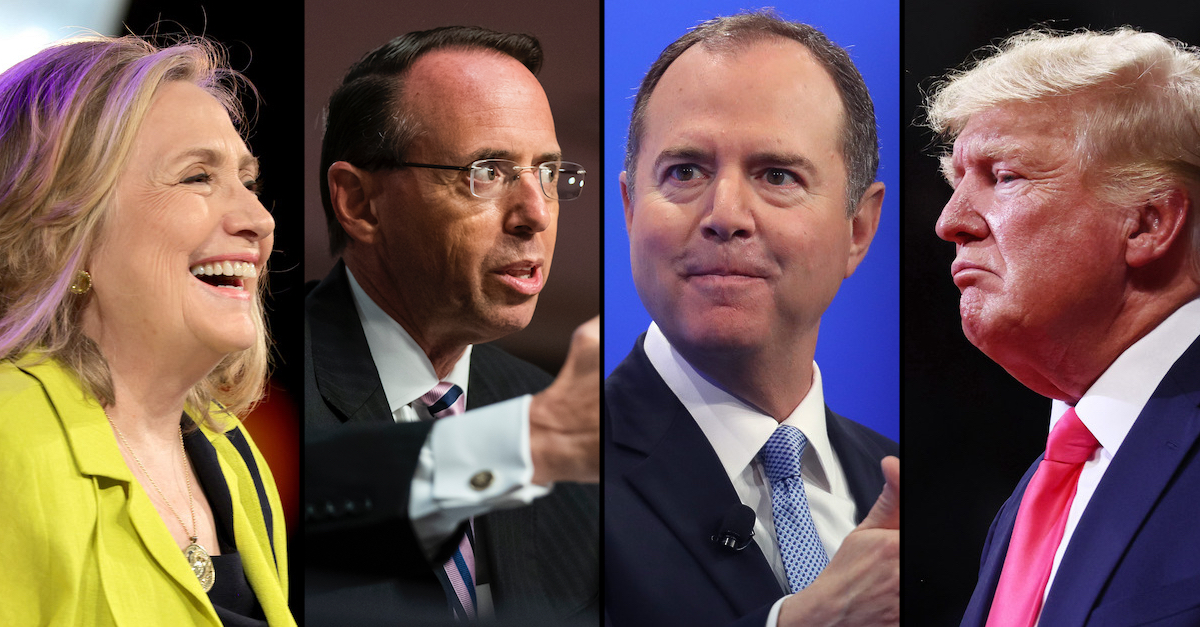

Hillary Clinton, Rod Rosenstein, Adam Schiff, and Donald Trump.

A federal judge has removed Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif. 28) and former Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein as defendants in a multi-million-dollar racketeering lawsuit launched by Donald Trump against Hillary Clinton and a number of his perceived political foes.

U.S. District Judge Donald M. Middlebrooks substituted the U.S. Government as the party to be sued in the absence of Schiff and Rosenstein.

The maneuver — known as a Westfall Act substitution — is similar to a recent move which yanked fired FBI director James Comey, fired FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe, fired FBI agent Peter Strzok, resigned FBI lawyer Lisa Page, and former FBI lawyer Kevin Clinesmith as personal defendants from the same lawsuit. (More on that section of the litigation later.)

The procedure allows the federal government, at its request, to step into the shoes of its employees when they are sued for acts undertaken in connection with their employment. Middlebrooks explained the law as follows; we’ve omitted the citations and internal punctuation:

The Westfall Act accords federal employees absolute immunity from common-law tort claims arising out of acts they undertake in the course of their official duties. The Westfall Act empowers the Attorney General (or his delegate) to certify that the employee was acting within the scope of his office or employment at the time of the incident out of which the claim arose. Upon such certification, the employees are dismissed from the action and the United States is substituted in their stead. This is automatic . . . [t]he United States remains the defendant unless and until the district court determines that the federal officer originally named as defendant was acting outside the scope of his employment.

James G. Touhey Jr., the director of the Torts Branch of the Civil Division of the Department of Justice, issued the necessary certification, Judge Middlebrooks noted. Therefore, Westfall Act substitution was triggered, and Schiff and Rosenstein were dismissed.

The next question Middlebrooks must answer is whether to dismiss the U.S. Government as the substituted party. Middlebrooks chose not to answer that question immediately, according to an order filed Friday.

The judge could also resurrect Schiff and Rosenstein as personal defendants if Trump’s lawyers successfully argue that they were acting outside the scope of their employment while committing the alleged wrongs.

The same day Middlebrooks dismissed Schiff and Rosenstein from the RICO action, the federal government moved to dismiss itself as the sole institutional defendant substituted for Comey, McCabe, Strzok, Page, and Clinesmith.

Those five defendants “all are former Federal Bureau of Investigation (‘FBI’) employees,” that motion asserts. “They were named as defendants only in two of the counts of plaintiff’s 16-count Amended Complaint, specifically those asserting claims for malicious prosecution and conspiracy to commit malicious prosecution.”

“Both of those claims relate to the five named former FBI employees’ alleged involvement in an FBI counterintelligence operation and associated Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) application processes,” the document continues. Therefore, the government argues, Comey, et al., “all were acting within the scope of their employment” and were properly replaced under a Westfall Act substitution request.

A later paragraph explains (again, citations are omitted):

Plaintiff brings claims of malicious prosecution and conspiracy to commit malicious prosecution against the former FBI employees based on their involvement in the counterintelligence investigation named Crossfire Hurricane and the FISA application process undertaken during that investigation. The former FBI employees were acting within the scope of their employment when engaging in the underlying activities out of which plaintiff’s claims are based, as counterintelligence operations and FISA surveillance are core activities of the FBI.

The same tone was repeated further in the document:

Applying these principles here, the alleged conduct of the five former FBI employees relating to the FBI’s counterintelligence investigation and associated FISA application processes all fits comfortably within the scope of their employment. Counterintelligence operations and FISA surveillance are activities that are undertaken by FBI employees on behalf of their employer. The alleged underlying activities out of which plaintiff’s claims for malicious prosecution and conspiracy to commit malicious prosecution arose relate to an FBI counterintelligence operation and associated FISA application processes and were therefore part of the former employees’ assigned duties. Accordingly, the substitution of the United States for Comey, McCabe, Strzok, Page, and Clinesmith was entirely proper.

After arguing that substitution was proper, the government asked Middlebrooks to dismiss Trump’s case against it “for lack of subject matter jurisdiction.” The asserted grounds were procedural: Trump “did not exhaust his administrative remedies under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA)” before filing his archlawsuit in federal court, the government averred.

Trump’s attorneys claimed Comey and the four others were working outside the scope of their employment and that discovery was warranted to resolve the dispute.

The government chided those asseverations but generally pointed Judge Middlebrooks squarely back to the procedural issue at hand.

“Plaintiff does not . . . deny that he instituted this action without first exhausting his administrative remedies under the FTCA, or argue that the action need not be dismissed as against the United States if the Court rejects his challenge to the United States’ substitution for the five former FBI employees,” the government wrote.

In other words, according to the government, Trump’s lawyers chose the wrong path when they filed the case.

Cutting closer to the merits, the government noted that while Trump alleged that Comey leaked documents after his departure from the FBI, Trump didn’t sue Comey for so doing: the claim Trump filed was instead “solely based on his conduct in conjunction with Crossfire Hurricane while he remained the Director of the FBI.” That claim asserted the “alleged falsification of evidence; alleged reliance on knowingly false information; allegedly withholding ‘pertinent and material information from FISA applications;’ and allegedly making ‘false and/or misleading statements to the FISC, Congress, and/or the Plaintiff,'” the government said while recapping Trump’s grievances.

“Even if the alleged leaks occurred,” the government wrote, “they have nothing to do with plaintiffs’ malicious prosecution and conspiracy to commit malicious prosecution claims, and thus do not preclude the substitution of the United States for Comey with respect to those claims.”

The government then suggested Trump’s resentments toward two other individuals fared no better (again, citations omitted):

Concerning Strzok and Page, plaintiff argues that a series of text messages they exchanged show that they held him in “utter disdain” and “engaged in a concerted effort to sabotage his presidential campaign.” But, as we have explained, whether an employee acts within the scope of his or her employment does not turn on the allegedly wrongful character of the acts at issue. Here, plaintiff’s allegations concerning Strzok and Page—that they participated in Crossfire Hurricane and were involved in the FISA application processes . . . relate to underlying activities that were part of their assigned duties as FBI employees. Moreover, even if Strzok and Page were only partially motivated by a desire to serve their employer (and plaintiff has not alleged that they were motivated solely by animus toward him or a personal political agenda), their conduct would still be within the scope of their employment.

“Conduct must be solely motivated by employee’s personal purposes in order to take it outside scope of employment,” the government then said, citing the relevant law on point.

Clinesmith was acting within the scope of his employment when he lied on an email as part of a FISA application, the government said.

“[U]nder District of Columbia law, intentional or criminal conduct can be within the scope of employment,” the government said.

Clinesmith was prosecuted over the matter and pleaded guilty.

The government’s filing then turned to McCabe:

Finally, plaintiff argues that McCabe acted outside the scope of his employment by approving FISA applications he knew were uncorroborated and false. Approving FISA applications was undeniably part of McCabe’s assigned duties as the Deputy Director of the FBI. As such, they clearly were within the scope of his employment as a matter of law.

The government asked Middlebrooks to deny Trump’s discovery request and to jettison the accusations against the government as a substituted party.

“Plaintiff has not pointed to any specific evidence that contradicts the [Westfall Act] certification decision and instead relies on conclusory allegations which, even if true, would not show that the FBI defendants acted outside of the scope of their employment,” the filings concludes.

One of the other named defendants, Orbis Business Intelligence Ltd., moved to dismiss the case against it as well.

Trump sued Clinton, her campaign, the Democratic National Committee, and others for allegedly violating racketeering and other laws by conspiring to malign Trump and his campaign during the 2016 election — which Trump won. The gravamen of the lawsuit is Trump’s complaint that the defendants cooked up a narrative surrounding Russian collusion and that their collective actions are redressable by a damages payment of $24 million.

Read the government’s filing and the judge’s order here:

[Images as follows: Clinton via Michael Loccisano/Getty Images; Rosenstein via Jim Lo Scalzo/Pool/Getty Images; Schiff via Win McNamee/Getty Images; Trump via Mario Tama/Getty Images.]