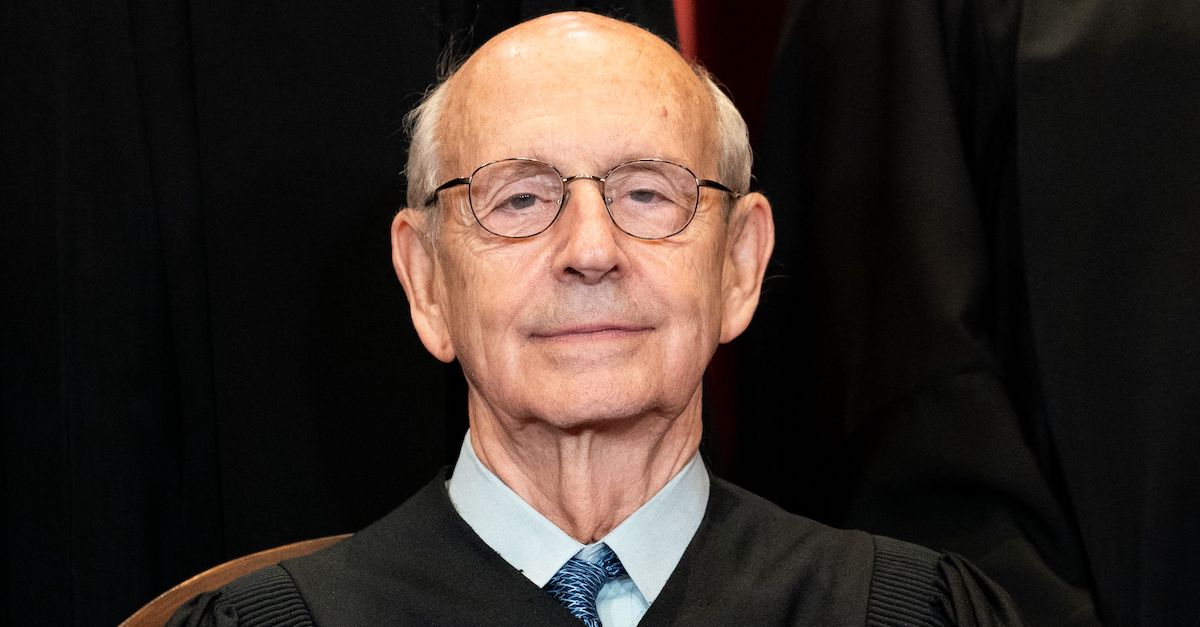

Associate Justice Stephen Breyer sits during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. on April 23, 2021.

The U.S. Supreme Court issued a lone opinion on Thursday which resolved a copyright registration dispute between fast fashion retail giant H&M and a California fabric design company — in favor of the latter.

The majority opinion by liberal Justice Stephen Breyer used an avian analogy to explain the court’s reasoning. A dissent by conservative Justice Clarence Thomas largely lodged procedural complaints about how the litigation played out in the courts.

In the controversy stylized as Unicolors, Inc v. H&M Hennes & Mauritz, LP, the nine justices were asked to consider whether a copyright registration that contains inaccurate information is still valid if the party that made the mistake didn’t actually know it was mistaken.

Unicolors sued H&M for copyright infringement — based on its prior registration of 31 different designs — after the retailer released an allegedly infringing jacket in 2016. H&M lost after a jury trial.

On appeal, H&M claimed the copyright registration for the fabric designs in question was fraudulent because Unicolors had made some, but not all, of the designs publicly available on the day the designs were registered — which is a necessary formality of copyright law. In the words of the relevant statute, H&M argued, Unicolors’ designs were not “included in a single unit of publication.”

The Ninth Circuit reversed the district court and remanded in H&M’s favor — which would have led to a hearing before the Register of Copyrights under Section 411(b) of the Copyright Act.

The Supreme Court, using descriptions of certain red birds to make the somewhat confusing point clear, reversed the Ninth Circuit:

A brief analogy may help explain the issue we must decide. Suppose that John, seeing a flash of red in a tree, says, “There is a cardinal.” But he is wrong. The bird is not a cardinal; it is a scarlet tanager. John’s statement is inaccurate. But what kind of mistake has John made?

John may have failed to see the bird’s black wings. In that case, he has made a mistake about the brute facts. Or John may have seen the bird perfectly well, noting all of its relevant features, but, not being much of a birdwatcher, he may not have known that a tanager (unlike a cardinal) has black wings. In that case, John has made a labeling mistake. He saw the bird correctly, but does not know how to label what he saw. Here, Unicolors’ mistake is a mistake of labeling. But unlike John (who might consult an ornithologist about the birds), Unicolors must look to judges and lawyers as experts regarding the proper scope of the label “single unit of publication.” The labeling problem here is one of law. Does that difference matter here? We think it does not.

“If Unicolors was not aware of the legal requirement that rendered the information in its application inaccurate, it did not include that information in its application ‘with knowledge that it was inaccurate.’ (emphasis added),” Breyer continued — framing the majority opinion as a straightforward application of the text of the copyright registration statute to the facts of the case. “Nothing in the statutory language suggests that this straightforward conclusion should be any different simply because there was a mistake of law as opposed to a mistake of fact.”

The prevailing concern for the dissent, which was argued unsuccessfully by H&M, is that the legal terrain shifted considerably between Unicolors’ original petition for writ of certiorari and the arguments their opponents made in their eventual brief.

Thomas, joined by Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch noted:

In its petition for certiorari, Unicolors asked us to decide a question on which the Courts of Appeals were split: whether §411(b)(1)(A)’s “knowledge” element requires “indicia of fraud.” Specifically, Unicolors argued that “knowledge” requires “inten[t] to defraud the Copyright Office.”

Yet now, after having “persuaded us to grant certiorari on this issue,” Unicolors has “chosen to rely on a different argument in [its] merits briefing.” It no longer argues that §411(b)(1)(A) requires fraudulent intent and instead proposes a novel “actual knowledge” standard. Because I would not reward Unicolors for its legerdemain, and because no other court had, before today, ever addressed whether §411(b)(1)(A) requires “actual knowledge,” I would dismiss the writ of certiorari as improvidently granted.

To hear H&M tell it, Unicolors pulled a bait-and-switch on the high court by first alleging a circuit split about fraud on the Copyright Office before shifting to their (eventually successful) knowledge argument. But, as SCOTUSBlog’s Ronald Mann previously reported, most of the justices verbally expressed that the issues were close enough, in terms of law, that they decided to apply the facts anyway.

In dissent, and in finally addressing the merits of the court’s decision in a section that was not joined by Gorsuch, Thomas assails the majority opinion for, in his opinion, basically rewriting the law.

“In this case, the Court’s misstep comes at considerable cost,” Thomas argues. “A requirement to know the law is ordinarily satisfied by constructive knowledge. Yet here, the Court imposes an actual-knowledge-of-law standard that is virtually unprecedented except in criminal tax enforcement.”

[image via ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images]