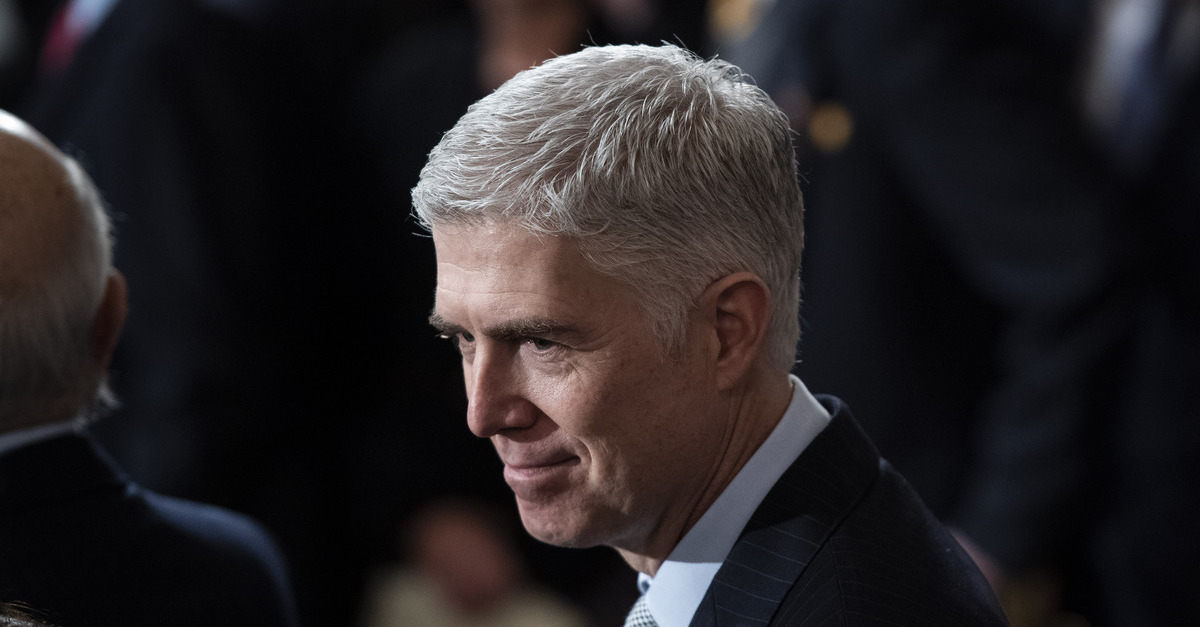

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch appears in a December 3, 2018 file photo. (Image by Jabin Botsford/Pool/Getty Images.)

The Supreme Court of the United States on Friday morning ruled that abortion providers can sue certain Texas officials over a restrictive anti-abortion law. The Texas law, known by its legislative moniker S.B. 8 or as the dubiously named “Heartbeat Act,” allows private individuals to sue abortion providers and others connected with abortion services if a pregnant person’s pregnancy is terminated after embryonic cardiac activity is detectable in a medical situation. That point occurs generally around six weeks into pregnancy.

By allowing for private civil lawsuits, but not enforcement by state actors themselves, the hotly-contested law was designed to skirt attempts by abortion providers to challenge it.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the law could, indeed, be challenged nonetheless — but the court strictly limited the types of federal enforcement abortion providers could seek. The opinion tacitly acknowledges — or perhaps even condones — the style of patchwork enforcement across myriad Texas counties that the abortion providers feared and hoped to stymie through federal court litigation. Recall that S.B. 8 explicitly allows every abortion provider to be limitlessly and endlessly sued over a single offending abortion. It also requires every abortion provider to potentially defend himself or herself in every single Texas county regardless of where the procedure was performed or where the provider lives. The law explicitly states that a judgment in favor of an abortion provider is not to be seen as precedent by any other judge in a parallel or subsequent case — meaning every S.B. 8 lawsuit must be fought on its own.

“The Court granted certiorari before judgment in this case to determine whether, under our precedents, certain abortion providers can pursue a pre-enforcement challenge to a recently enacted Texas statute,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote for the court. “We conclude that such an action is permissible against some of the named defendants but not others.”

The court held as follows: First, the cases by the abortion providers against Penny Clarkston (a state-court clerk) and Austin Jackson (a state court judge) should be dismissed under the doctrine of sovereign immunity — in other words, that states are generally immune from such lawsuits under the 11th Amendment. Second, the case against Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R) should also be dismissed he basically had no cognizable enforcement power under the law. Third, the case against Mark Lee Dickson, the director of Right to Life East Texas, should also be dismissed because Dickson said he had no intent to file S.B. 8 lawsuits against abortion providers.

Fourth, however, the court said cases against Stephen Carlton, Katherine Thomas, Allison Benz, and Cecile Young could continue. “Each of these individuals is an executive licensing official who may or must take enforcement actions against the petitioners if they violate the terms of Texas’s Health and Safety Code, including S.B. 8,” the court held. “Accordingly,” the majority continued, “sovereign immunity does not bar the petitioners’ suit against these named defendants at the motion to dismiss stage.”

The decision is unlikely to grant much comfort to the pro-choice camp. Though “eight Members of the Court agree sovereign immunity does not bar the petitioners from bringing this pre-enforcement challenge in federal court,” the majority noted that “everyone acknowledges that other pre-enforcement challenges may be possible in state court as well.” The opinion continues:

In fact, 14 such state-court cases already seek to vindicate both federal and state constitutional claims against S.B. 8 — and they have met with some success at the summary judgment stage. Separately, any individual sued under S.B. 8 may pursue state and federal constitutional arguments in his or her defense. Still further viable avenues to contest the law’s compliance with the Federal Constitution also may be possible; we do not prejudge the possibility.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor chalked up that possibility as nothing but sheer chaos.

“The Court should have put an end to this madness months ago, before S.B. 8 first went into effect,” the justice wrote while pointing to the current federal enshrinement of abortion rights in Supreme Court case law. “It failed to do so then, and it fails again today.”

But Gorsuch’s majority opinion snapped back at her:

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR’S suggestion that the Court’s ruling somehow “clears the way” for the “nullification” of federal law along the lines of what happened in the Jim Crow South not only wildly mischaracterizes the impact of today’s decision, it cheapens the gravity of past wrongs.

The truth is, too, that unlike the petitioners before us, those seeking to challenge the constitutionality of state

laws are not always able to pick and choose the timing and preferred forum for their arguments. This Court has never recognized an unqualified right to pre-enforcement review of constitutional claims in federal court.[ . . . ]

Finally, JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR contends that S. B. 8 “chills” the exercise of federal constitutional rights. If nothing else, she says, this fact warrants allowing further relief in this case. Here again, however, it turns out that the Court has already and often confronted — and rejected — this very line of thinking. As our cases explain, the “chilling effect” associated with a potentially unconstitutional law being “‘on the books’” is insufficient to “justify federal intervention” in a pre-enforcement suit. Instead, this Court has always required proof of a more concrete injury and compliance with traditional rules of equitable practice. The Court has consistently applied these requirements whether the challenged law in question is said to chill the free exercise of religion, the freedom of speech, the right to bear arms, or any other right. The petitioners are not entitled to a special exemption.

Earlier in the opinion, Gorsuch recapped, in part, the procedural posture of the case; he then explained why the hasty opinion came down when it did. Oral arguments in the case were heard on Nov. 1, and the merits opinion came down Dec. 10. That’s close to lightning speed:

After the law’s adoption, various abortion providers sought to test its constitutionality. Not wishing to wait for S.B. 8 actions in which they might raise their arguments in defense, they filed their own pre-enforcement lawsuits. In all, they brought 14 such challenges in state court seeking, among other things, a declaration that S.B. 8 is inconsistent with both the Federal and Texas Constitutions. A summary judgment ruling in these now-consolidated cases arrived last night, in which the abortion providers prevailed on certain of their claims.

In conclusion, Gorsuch and the majority cited the papers of John Marshall and ruled in favor of a limited forum in the federal court system for abortion providers to seek broad-ranging federal enforcement of what currently, under Planned Parenthood v. Casey and Roe v. Wade, is a federal constitutional right.

[O]ne thing this Court may never do is disregard the traditional limits on the jurisdiction of federal courts just to see a favored result win the day. At the end of that road is a world in which “[t]he division of power” among the branches of Government “could exist no longer, and the other departments would be swallowed up by the judiciary.”

Casey and Roe, of course, are themselves currently also being challenged and may be overturned by another case currently before the court. Under Casey, states may not constitutionally place an “undue burden” on a woman’s ability to obtain an abortion prior to fetal viability. That point — when the fetus can live on its own outside its mother’s body — generally occurs at about 24 weeks. That’s long after the current six-week cardiac activity standard currently enshrined in S.B. 8.

Gorsuch then recapped the holding of the case:

The petitioners’ theories for relief face serious challenges but also present some opportunities. To summarize: (1) The Court unanimously rejects the petitioners’ theory for relief against state-court judges and agrees Judge Jackson should be dismissed from this suit. (2) A majority reaches the same conclusion with respect to the petitioners’ parallel theory for relief against state-court clerks. (3) With respect to the back-up theory of relief the petitioners present against Attorney General Paxton, a majority concludes that he must be dismissed. (4) At the same time, eight Justices hold this case may proceed past the motion to dismiss stage against Mr. Carlton, Ms. Thomas, Ms. Benz, and Ms. Young, defendants with specific disciplinary authority over medical licensees, including the petitioners. (5) Every Member of the Court accepts that the only named private-individual defendant, Mr. Dickson, should be dismissed.

The full opinion is below:

This is a developing story.

Legal citations have been omitted from many of the quotes in this piece.