The Supreme Court of the United States handed down another unanimous opinion Thursday in City of San Antonio v. Hotels. Com, L.P., the fifth unanimous decision in the last two weeks. The 9-0 Court ruled against the city of San Antonio, Texas, holding that a district court is not authorized to second-guess the ruling of a federal appeals court on costs awarded to the winner of an appeal.

To understand the dispute at hand, we must first look back at the class-action lawsuit that gave rise to the appeal. The case centered around service fees charged by online travel companies (OTCs), such as Orbitz and Expedia.

San Antonio and 172 other Texas municipalities had been looking to collect back-taxes from a number of OTCs, such as Hotels dot-com, Hotwire, Expedia, Priceline dot-com. The municipalities filed a class action lawsuit, part of which argued that taxes owed by OTCs should be calculated based on the “retail rate” contracted (meaning discounted room rate plus service fees), as opposed to just the discounted room rate. The cities won a $55 million judgment, and the federal district court held that the full retail rate that was subject to taxation.

In something of a legal traffic jam, however, the exact same question was being decided in Texas state court in a wholly separate lawsuit. The Texas court came to the opposite conclusion: that only the discounted room rate should be taxed.

The OTCs appealed their loss in federal court to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. On appeal, the OTCs won, and the Fifth Circuit reversed. A party that wins an appellate lawsuit is entitled to petition for fees and costs under Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 39. That’s just what the OTCs did, filing a bill for $905.60 with the appellate clerk for filing fees. The Fifth Circuit approved the bill and (as is the usual practice, and over no one’s objection), taxed those costs.

It is what happened next that gave rise to the Supreme Court case.

The OTCs had far heftier costs than a mere $905. They’d also incurred $2.3 million in costs in premiums for something called “supersedeas bonds”; these are sureties routinely used in large-scale litigation to provide security while the appeals process is pending. The OTCs filed a bill to be reimbursed for the supersedeas premiums with the district court, and asked that those costs also be taxed. The district court generally agreed, and taxed $2.2 million of the costs.

The cities, now on the hook for a substantial bill, asked the district court to reduce the amount they were required to pay to the winning OTCs. The district court refused to do so, reasoning that it had no authority to change appellate cost awards under Rule 39.

The cities appealed, and both the Fifth Circuit and now the Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s refusal. The decision, which settles a split among the federal circuits on the matter, clarified that in matters of appellate costs, appellate courts are in charge.

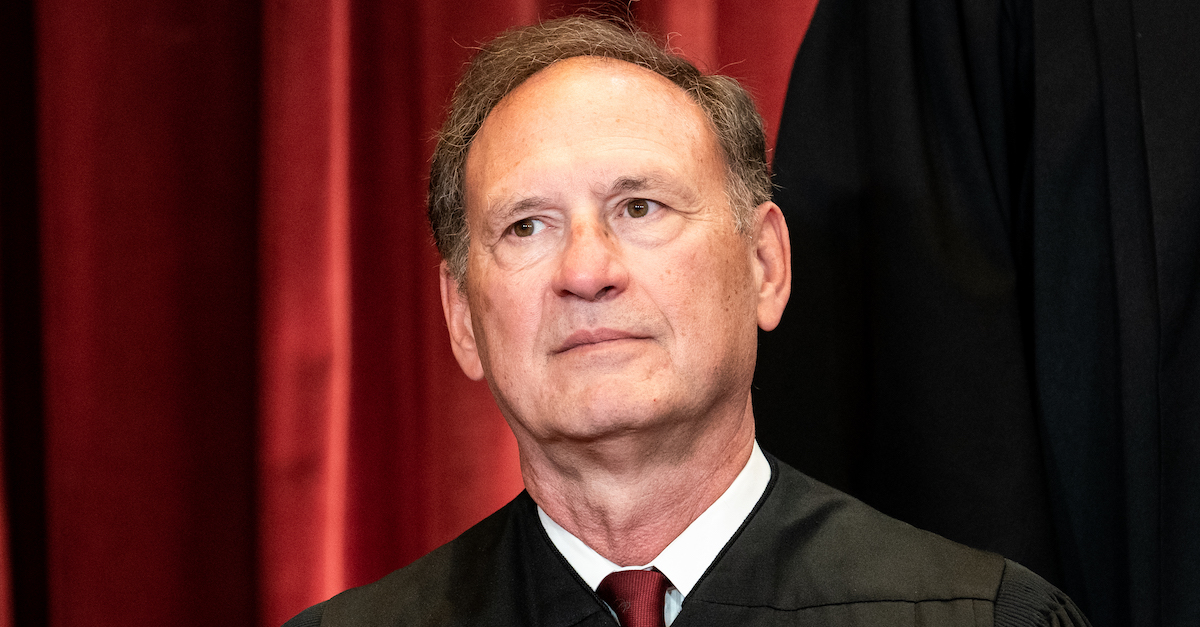

Justice Samuel Alito delivered the opinion for the unanimous court.

“There is a longstanding tradition of awarding certain costs other than attorney’s fees to prevailing parties in the federal courts,” he began. He continued, underscoring the appellate courts’ authority to allocate costs in the way they see fit. The applicable statute “certainly does not suggest that the court of appeals may not divide up costs,” he wrote. “On the contrary, the authority of a court of appeals to do just that is strongly supported by the relationship between the default rules and the court of appeals’ authority to ‘order otherwise.'”

Alito went on to describe the potential for legal havoc if a district court could second guess a higher court’s ruling on costs:

Suppose that a court of appeals, in a case in which the district court’s judgment is affirmed, awards the prevailing appellee 70% of its costs. If the district court, in an exercise of its own discretion, later reduced those costs by half, the appellee would receive only 35% of its costs—in direct violation of the court of appeals’ directions. Or suppose that the court of appeals, believing that the decision below was plainly wrong, awards the prevailing appellant 100% of its costs. It would subvert that allocation if the district court declined to tax costs or substantially reduced them because it thought that there was at least a very strong argument in favor of the decision that the court of appeals had reversed—which, of course, was the district court’s own decision. In short, the court of appeals’ determination that a party is “entitled” to costs would mean little if, as San Antonio believes, the district court could take a second look at the equities.

Appellate courts should deal with appellate costs, and district courts should deal with trial costs, Alito explained. “We do not see why our interpretation will lead to confusion,” he wrote, dispensing with San Antonio’s argument. “This interpretation quite sensibly gives federal courts at each level primary discretion over costs relating to their own proceedings.”

Speaking for the whole court, Justice Alito also made short work of neutralizing San Antonio’s argument that district courts should determine cost allocations, because there may be facts relevant to those decisions.

“For example,” Alito allowed, “a party might suggest that taxing costs against it would be unjust because of its precarious financial position, and an opposing party might dispute that contention on factual grounds.” Ultimately, though, Alito simply found, “These concerns are overblown.” According to the justice, “[m]ost appellate costs are readily estimable, rarely disputed, and frankly not large enough to engender contentious litigation in the great majority of cases.” He called the $2.3 million in bond premiums “something of an anomaly.”

Just how “overblown” concerns about sometimes-exorbitant appellate costs are is a matter about which there has been disagreement among the federal circuits. The nation’s highest jurists, though, appear to be of one mind: appellate courts are the right entities to decide matters of appellate money.

[Image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]