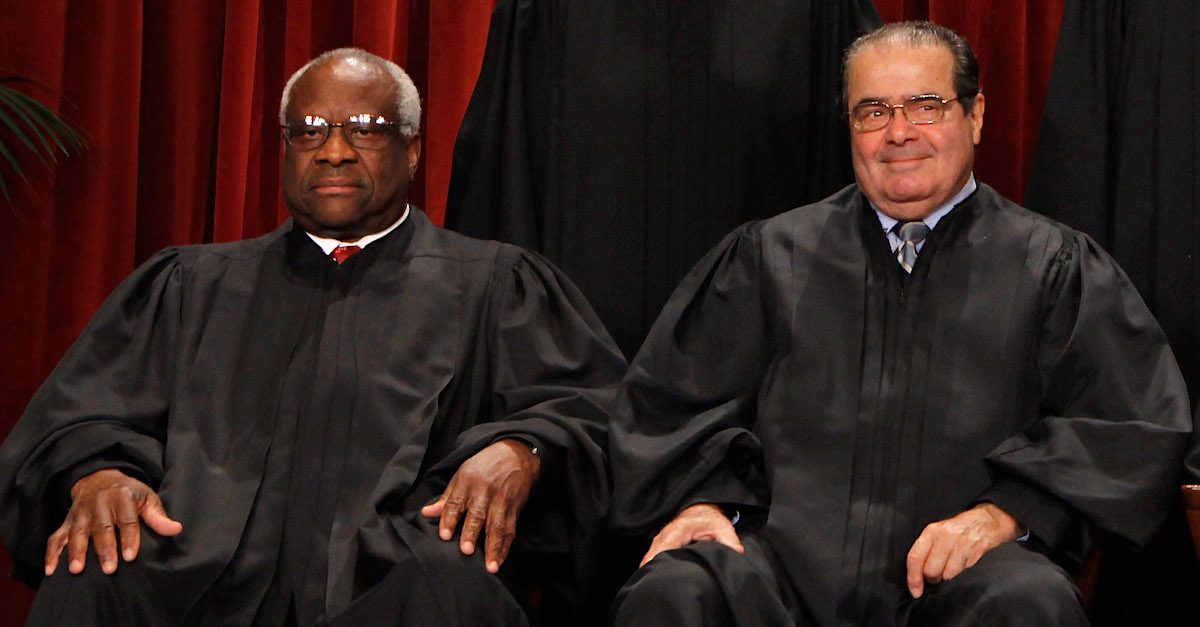

Justices Clarence Thomas and Antonin Scalia were seated together on Oct. 8, 2010, during the Supreme Court’s formal portrait.

Conservatives and Republicans have used a recent nationwide baby formula shortage to attack the administration of President Joe Biden for providing formula to the infants of incarcerated immigrants along the U.S. Border. What’s ironic is that conservative jurist Antonin Scalia and a 7-2 bloc of Supreme Court conservatives signed an opinion in 1993 that indicated the government needed to provide “decent and humane” facilities — including appropriate nourishment — for detainees.

The newfound critics of the provision of formula to infants at the border include Rep. Kat Cammack (R-Fla.), Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-N.Y.), and Gov. Greg Abbott (R-Texas), among others. Some of the widely disseminated pictures which purported to show formula have been subsequently identified as powdered milk.

When asked about why the Biden Administration was providing formula to migrants, outgoing White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki pointed to a settlement connected to Reno v. Flores, a 1993 U.S. Supreme Court case. Psaki’s colloquy during Friday’s press briefing went like this:

Q: Okay. Congresswoman Elise Stefanik — and she tweeted something I will read to you — but several other Republican politicians have also gone along this line. She says, “Joe Biden continues to put America last by shipping pallets of baby formula to the southern border as American families face empty shelves.” She says, “This is unacceptable.” Do you have a response to that?

MS. PSAKI: Well, we do like facts here, so let me just give you a little sense of the facts on this one. There’s something called the Flores statemen- — Settlement, which she may or may not be aware of, that’s been in place since 1997. It requires adequate food and elsewhere, specifies age appropriateness, hence formula for kids under the age of one.

CBP is following the law — that law that has been in place and been followed, by the way, by the past — every administration since 1997.

So this has been a law in the United States for a quarter century. It’s been followed by every administration. And on — but I would also note that we also think it’s morally the right thing to do. You know, and this is a difference from the last administration. It is the law, but we believe that when children and babies — or babies, I should say, are crossing the border with a family member, that providing them formula — formula is morally right. And so we certainly support the implementation of it.

Psaki also noted that the formula shortage was primarily connected to “a recall in February” that resulted from “a factory in Michigan that had tainted formula that killed two babies.”

Let’s look at the underlying law.

In Reno v. Flores, Justice Scalia wrote for a 7-2 majority made up of the Court’s conservatives, moderates, and even some of its eventual liberals. Rounding out the majority were Justices Clarence Thomas, William Rehnquist, Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony Kennedy, Byron White, and David Souter. Justices John Paul Stevens and Harry Blackmun were in the dissent.

Put in more blunt terms, the appointees of Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and John F. Kennedy were in the majority. (Stevens and Blackmun were appointed by Gerald Ford and Nixon, respectively.)

Scalia’s introduction to Flores could be equally as applicable to the debates of 1992 and 1993 as it is today.

“Over the past decade, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS or Service) has arrested increasing numbers of alien juveniles who are not accompanied by their parents or other related adults,” Scalia wrote.

After noting that the attorney general had “broad discretion” in determining how to handle and whether to release adults arrested at the border, Scalia said that children were different.

“In the case of arrested alien juveniles,” the patriarch of modern conservative jurists wrote, “the INS cannot simply send them off into the night on bond or recognizance.”

The issue in the case was in essence whether the “thousands of alien juveniles” rounded up every year without being accompanied by an adult had a right to be released from custody pending further proceedings:

The parties to the present suit agree that the Service must assure itself that someone will care for those minors pending resolution of their deportation proceedings. That is easily done when the juvenile’s parents have also been detained and the family can be released together; it becomes complicated when the juvenile is arrested alone, i. e., unaccompanied by a parent, guardian, or other related adult. This problem is a serious one, since the INS arrests thousands of alien juveniles each year (more than 8,500 in 1990 alone) — as many as 70% of them unaccompanied. Most of these minors are boys in their midteens, but perhaps 15% are girls and the same percentage 14 years of age or younger.

After walking through myriad nuances in federal statutes which govern the detention of immigrants at the border, Scalia wrote — and the majority held — that children detained by the government had no “fundamental right” (that’s a constitutional term of art) to demand a release from custody while their immigration hearings were pending. But there were caveats. Scalia premised his argument in favor of juvenile detention on the assumption that the government was providing “a decent and humane custodial institution” in which to house the children while they were detained.

Put another way, Scaila wrote as follows, again affirming that children detained at the border had no “fundamental right” to be released into what he called a “private placement” — e.g., with a friend or relative:

Where a juvenile has no available parent, close relative, or legal guardian, where the government does not intend to punish the child, and where the conditions of governmental custody are decent and humane, such custody surely does not violate the Constitution.

Scalia thus dispatched with what the Court called the “substantive due process” claims (which involve broad, capacious, and at times lofty rights unrelated to pure legal procedures) and moved on to address the “procedural due process” concerns (those are issues that deal with — you guessed it — legal procedures and the neutrality of the arbiter afforded).

“It is well established that the Fifth Amendment entitles aliens to due process of law in deportation proceedings,” Scalia wrote while citing The Japanese Immigrant Case (1903) and reaffirming a principle that is the foil of many recent conservative talking points.

Again came a walk through the specific immigration procedures then at play; Scalia and the majority found those procedures sufficient.

The next challenge questioned whether the attorney general exceeded his lawful authority by adopting an administrative regulation in contravention of a broader and legally superior federal statute. Here, Scalia ruled that the AG was not forced to undertake exhaustive efforts to place immigrant children in care situations outside federal detention centers because the broader law did not explicitly require herculean measures. Or, in other words, “a detention program justified by the need to protect the welfare of juveniles is not constitutionally required to give custody to strangers if that entails the expenditure of administrative effort and resources that the Service is unwilling to commit.” Relatives and friends, however, were consulted to house detained children, Scalia wrote.

Justices O’Connor and Souter penned a separate concurrence to opine that the procedures then utilized by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the precursor to several modern departments of government, were sufficient under the Due Process Clause.

Like the majority opinion, the concurrence explicitly stated that its theorems and promulgations were predicated upon an underlying assumption that the government’s holding pens were “decent and humane.”

To be clear, the words “food,” “water,” and “formula” appear nowhere in the actual Flores opinion, but its framework — that the government can lock children up at the border — was all pinned upon the supposition that “decent and humane” government facilities were being provided during the term of incarceration.

The Flores opinion glossed the specifics of what “decent and humane” facilities might look like because the opinion directly referenced another document, which the Court called the “Juvenile Care Agreement” for short. That document’s promises morphed into what has been called the Flores Settlement Agreement — the document referenced by the White House on Friday.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, the Settlement Agreement requires the feds to favor the release of detained children to “a parent, legal guardian, adult relative or licensed program.” It also requires the feds to provide “safe and sanitary facilities, toilets and sinks, drinking water and food, medical assistance, temperature control, supervision, and contact with family members, among other requirements.”

The history of the Settlement Agreement has been fraught with controversy and was re-litigated in the lower courts during the Trump Administration. Critics have called Flores itself a “significant win” for the government because it held ultimately that immigrants have few constitutional rights. But the original opinion also laid plain the ramifications of the federal government’s immigration enforcement tactics.

“The consequences of an erroneous commitment decision are more tragic where children are involved,” the O’Connor/Souter concurrence noted by quoting an earlier case. “Childhood is a particularly vulnerable time of life and children erroneously institutionalized during their formative years may bear the scars for the rest of their lives.”

When reduced to a perhaps oversimplified holding, the case comes out to basically this: if the government wants to lock up immigrant children at the border, it needs to provide “decent and human” facilities for their incarceration; in the case of infants, that means formula. Indeed, the food must be “appropriate,” the Settlement Agreement states.

In a dissent, Justices Stevens and Blackmun were the ones who bemoaned via a footnote the exorbitant costs involved with detaining children. They favored a release from custody pending further immigration proceedings.

[image via Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images]