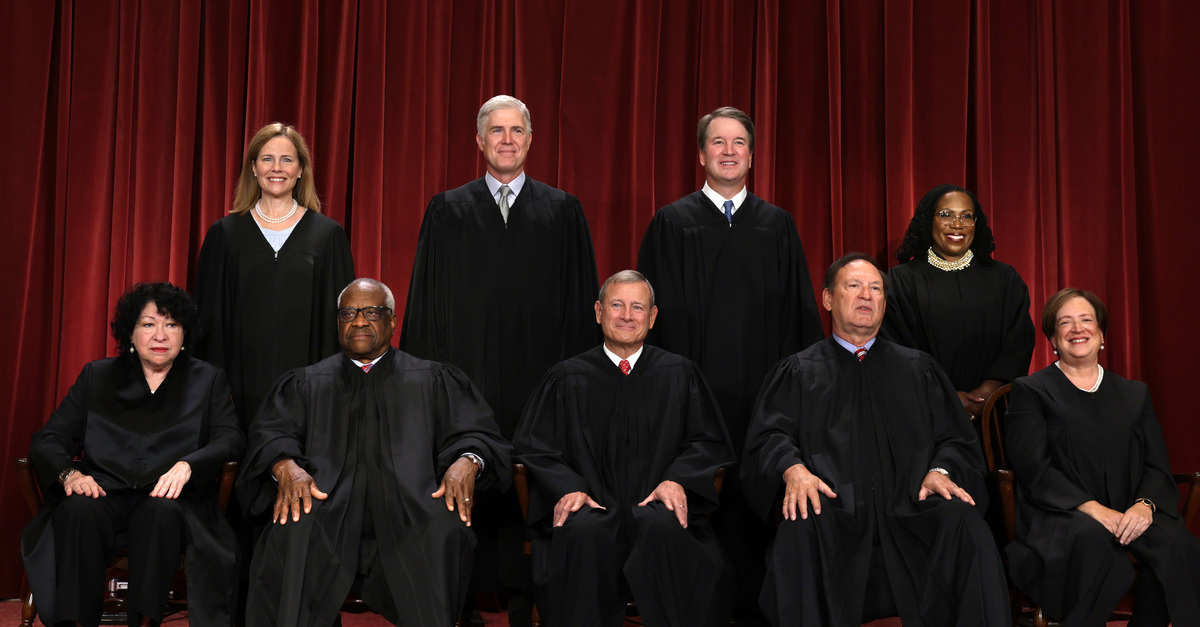

United States Supreme Court (front row L-R) Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan, (back row L-R) Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pose for their official portrait at the East Conference Room of the Supreme Court building.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to consider a challenge to a series of racist Supreme Court precedents that have, for over 100 years, denied residents of U.S. colonies full U.S. citizenship and rights. No dissents from the order maintaining those cases were recorded.

“It’s a punch in the gut for the justices to leave in place a ruling that says I am not equal to other Americans simply because I was born in a U.S. territory,” lead plaintiffs, John Fitisemanu said in a statement. “I was born on U.S. soil, have a U.S. passport, and pay my taxes like everyone else. But because of a discriminatory federal law, I am not recognized as a U.S. citizen. As a result, I can’t even vote in local elections, much less for president. This is un-American and cannot be squared with America’s democratic and constitutional principles.”

In the case stylized as Fitisemanu v. United States, three American Samoans challenged a federal statute that denies birthright citizenship to people born in American Samoa and which declares them to be “nationals, but not citizens, of the United States.”

The parties’ attorneys argued in their denied petition:

Text, history, and relevant precedents all uniformly show that this statute is unconstitutional because U.S. Territories like American Samoa are “in the United States” within the meaning of the Citizenship Clause. But a divided panel of the Tenth Circuit upheld the statute pursuant to the infamous Insular Cases. The choice for this Court, then, is clear: it can either give its sanction to the panel majority’s extension of the Insular Cases, or it can uphold the original meaning of and binding precedent interpreting the Citizenship Clause, and thereby safeguard the right to birthright citizenship for people born in U.S. Territories.

“The subordinate, inferior non-citizen national status relegates American Samoans to second-class participation in the Republic,” attorneys for the Utah-based petitioners go on to write. “As non-citizens, for example, they cannot run for President or serve as Representatives or Senators in Congress. And those in Utah or other States are barred from voting for the federal, state, and local elected officials who determine what rights non-citizen nationals enjoy.”

The specific question before the nation’s high court was whether or not the 14th Amendment’s citizenship clause supersedes the federal statute purporting to treat American Samoa, and its people, different from the rest of the U.S. colonial “possessions” in the Pacific Ocean.

Because the appellate court upheld the statute as constitutional under explicitly racist Supreme Court precedent – the Insular Cases – the denial of the petition for writ of certiorari shows at least six justices were comfortable with allowing those cases to stand (you need four of the nine justices to grant cert).

Penned in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, the Insular Cases is a term that encompasses several Supreme Court decisions that, in sum, said the U.S. government can treat the territories obtained from Spain (and additional islands later added to the colonial satchel, like American Samoa) differently than U.S. states due to the racial composition of the people who lived on those strips of land.

One notorious case, referring to the “American Empire,” explained the government’s logic in the following terms: “[our island] possessions are inhabited by alien races, differing from us in religion, customs, laws, methods of taxation, and modes of thought, the administration of government and justice according to Anglo-Saxon principles.”

The majority opinion in that case, Downes v. Bidwell, was written by Justice Henry Billings Brown – infamous for authoring the Plessy v. Ferguson decision that blessed racial segregation. A concurrence to the opinion by Justice Edward Douglass White stakes out similar rhetorical bearings with reference to the colonized peoples controlled by the U.S. government and by using antiquated notions of conquest.

“Take a case of discovery,” the concurrence reads. “Citizens of the United States discover an unknown island, peopled with an uncivilized race, yet rich in soil, and valuable to the United States for commercial and strategic reasons. Clearly, by the law of nations, the right to ratify such acquisition and thus to acquire the territory would pertain to the government of the United States.”

While scholars disagree about the extent of the opinions that constitute the Insular Cases – as few as eight written only in 1901 up to over two dozen extending to those written in 1979 – the upshot of those rulings have created a patchwork system of rights, duties, and statuses for people born and living in U.S. colonies.

And, while American Samoa is the last remaining colony where birthright citizenship is explicitly foreclosed against, the disparate treatment of the people living under the U.S. government without full citizenship and rights is still a subject of intense and steady litigation.

In April of this year, the Supreme Court ruled, in an 8-1 opinion, that Puerto Ricans are not entitled to the full Social Security system – denying them access to Supplemental Security Income payments.

The lone dissent in that case was written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Justice Neil Gorsuch, in concurrence, wrote separately to opine that it was high time for the court to reject the Insular Cases but noted that the issue was not explicitly raised by any of the parties.

“A century ago in the Insular Cases, this Court held that the federal government could rule Puerto Rico and other Territories largely without regard to the Constitution,” Gorsuch wrote. “It is past time to acknowledge the gravity of this error and admit what we know to be true: The Insular Cases have no foundation in the Constitution and rest instead on racial stereotypes. They deserve no place in our law.”

Monday’s decision to vindicate the Insular Cases is a marked setback for those seeking equality of law and full civil rights for people born and living in U.S. colonies – particularly because of Gorsuch’s disdain for those precedents which gave advocates hope that a change in regime was on the horizon.

It’s unclear whether Gorsuch reversed course or any number of the justices appointed by Democrats decided against revisiting the racist logic that still controls U.S. colonial law.

“Today’s inaction by the justices highlights the fact that America has a colonies problem,” Neil Weare, co-counsel for the American Samoan petitioners said in a statement provided to Law&Crime. “On top of that, our country stubbornly refuses to recognize that this problem even exists, much less do anything about it. The population of the five U.S. territories is equal to that of the five smallest states, yet residents of the territories – 98% of whom are people of color – cannot vote for President, have no voting representation in Congress, and are systematically denied their right to self-determination.”

Weare said the Supreme Court’s silence on the issue speaks volumes:

The Supreme Court’s refusal to reconsider the Insular Cases today continues to reflect that ‘Equal Justice Under Law’ does not mean the same thing for the 3.6 million residents of U.S. territories as it does for everyone else. The Supreme Court in recent years has not hesitated to rule in ways that harm residents of U.S. territories. But when asked to stand up for the rights of people in the territories – even the basic right to citizenship – the justices are silent.

[image via Alex Wong/Getty Images]