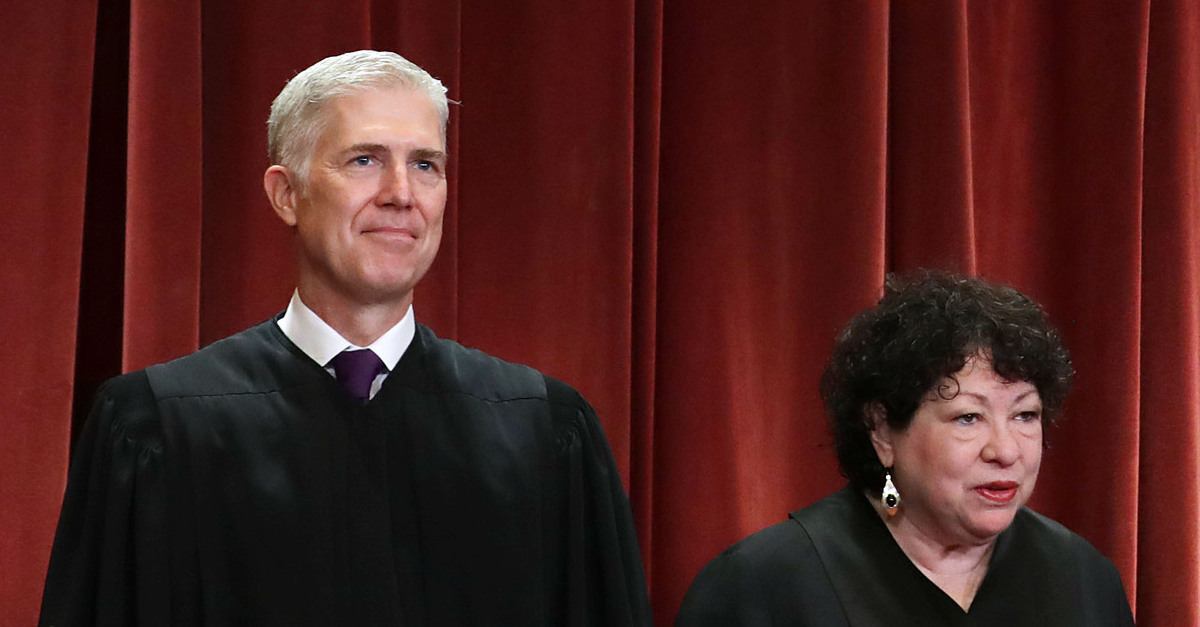

United States Supreme Court Justices Neil Gorsuch (L) and Sonia Sotomayor (R) pictured posing for an official court photo.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday overruled decades of precedent maintaining the separation of church and state in a case about a former high school football coach who was fired for engaging in visible, public prayers at the 50-yard line after every game.

The Court’s 6-3 decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton, in a majority opinion penned by Justice Neil Gorsuch, formally overrules the landmark 1971 Lemon v. Kurtzman case as well as a test long used to determine whether a challenged government action gives the impression to a reasonable observer constitute an “endorsement” of religion by the state.

In two fell swoops of jurisprudential revision, the U.S. Constitution’s Establishment Clause has – as part of a consistent trend established with the Rehnquist Court and exacerbated by the Roberts Court – been heavily reworked to elide concerns about religious coercion in the context of public school students and authority figures.

The activity at the center of the case was what both the majority and the dissent — penned by Justice Sonia Sotomayor — described as “demonstrative” religious activity. For years, then-coach Joseph Kennedy, a public school employee, performed a prayer at the 50-yard line after every football game. He also led students in prayer after each game, and occasionally in the locker room – both pregame and postgame.

The district was concerned that Kennedy was violating the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, and moved to restrict their potential liability. The majority dispensed with concerns about the prayers involving students by noting Kennedy was only fired after a series of interactions with the Bremerton School District by way of lawyer letters that demanded he severely curtail his conspicuous religious activity. He more or less did so and, in the end, refrained from leading students in prayer, but he increasingly made a media spectacle of his praying.

In retelling the events, however, the majority and the dissent offer noticeably distinct verbiage to describe how the situation came to a head in federal court after the coach was finally fired.

The majority offers this version:

After the October 23 [2015] game ended, Mr. Kennedy knelt at the 50-yard line, where “no one joined him,” and bowed his head for a “brief, quiet prayer.” The superintendent informed the District’s board that this prayer “moved closer to what we want,” but nevertheless remained “unconstitutional.” After the final relevant football game on October 26, Mr. Kennedy again knelt alone to offer a brief prayer as the players engaged in postgame traditions. While he was praying, other adults gathered around him on the field.

And here’s how the dissent explained things:

[H]is attorneys told the media that he would accept only demonstrative prayer on the 50-yard line immediately after games. During the October 23 and October 26 games, Kennedy again prayed at the 50-yard line immediately following the game, while postgame activities were still ongoing. At the October 23 game, Kennedy kneeled on the field alone with players standing nearby. At the October 26 game, Kennedy prayed surrounded by members of the public, including state representatives who attended the game to support Kennedy. The BHS players, after singing the fight song, joined Kennedy at midfield after he stood up from praying.

With cameras trained on the prayer events, parents complaining about their children feeling coerced, and politicians making hay out of the situation, Kennedy was given his first ever negative performance review and did not come back the next season. The school said his behavior, however amended, was still “unconstitutional” because it gave the appearance that the district endorsed what he was doing on the field that only players and school employees could access.

“That reasoning was misguided,” the majority ruled. “Both the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment protect expressions like Mr. Kennedy’s. Nor does a proper understanding of the Amendment’s Establishment Clause require the government to single out private religious speech for special disfavor.”

In replacing the long-reviled-by-conservatives Lemon test and the Sandra Day O’Connor-created endorsement test, the majority opinion advises lower courts to adopt a two-step process that takes into account “the complexity associated with the interplay between free speech rights and government employment.”

The majority opinion at length:

The first step involves a threshold inquiry into the nature of the speech at issue. If a public employee speaks “pursuant to [his or her] official duties,” this Court has said the Free Speech Clause generally will not shield the individual from an employer’s control and discipline because that kind of speech is—for constitutional purposes at least—the government’s own speech.

At the same time and at the other end of the spectrum, when an employee “speaks as a citizen addressing a matter of public concern,” our cases indicate that the First Amendment may be implicated and courts should proceed to a second step. At this second step, our cases suggest that courts should attempt to engage in “a delicate balancing of the competing interests surrounding the speech and its consequences.” Among other things, courts at this second step have sometimes considered whether an employee’s speech interests are outweighed by “‘the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees.’”

“Kennedy has demonstrated that his speech was private speech, not government speech,” Gorsuch writes, applying the test. “When Mr. Kennedy uttered the three prayers that resulted in his suspension, he was not engaged in speech ‘ordinarily within the scope’ of his duties as a coach. He did not speak pursuant to government policy. He was not seeking to convey a government-created message. He was not instructing players, discussing strategy, encouraging better on-field performance, or engaged in any other speech the District paid him to produce as a coach. Simply put: Mr. Kennedy’s prayers did not ‘ow[e their] existence’ to Mr. Kennedy’s responsibilities as a public employee.”

In dissent, Sotomayor (joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan) all but accuse the majority of weakening the Establishment Clause so much that it effectively functions as part of the Free Exercise Clause. Or, in other words, of rolling them into one.

“The Free Exercise Clause and Establishment Clause are equally integral in protecting religious freedom in our society,” the dissent says. “The first serves as ‘a promise from our government,’ while the second erects a ‘backstop that disables our government from breaking it’ and ‘start[ing] us down the path to the past, when [the right to free exercise] was routinely abridged.’ Today, the Court once again weakens the backstop.”

Key for Sotomayor is the fact of the coach’s relationship to his players in a public school setting – and the attendant coercion that might arise when a person in a position of power engages in religious displays.

Again, the dissent:

[The majority opinion] elevates one individual’s interest in personal religious exercise, in the exact time and place of that individual’s choosing, over society’s interest in protecting the separation between church and state, eroding the protections for religious liberty for all. Today’s decision is particularly misguided because it elevates the religious rights of a school official, who voluntarily accepted public employment and the limits that public employment entails, over those of his students, who are required to attend school and who this Court has long recognized are particularly vulnerable and deserving of protection. In doing so, the Court sets us further down a perilous path in forcing States to entangle themselves with religion, with all of our rights hanging in the balance. As much as the Court protests otherwise, today’s decision is no victory for religious liberty.

[ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images]