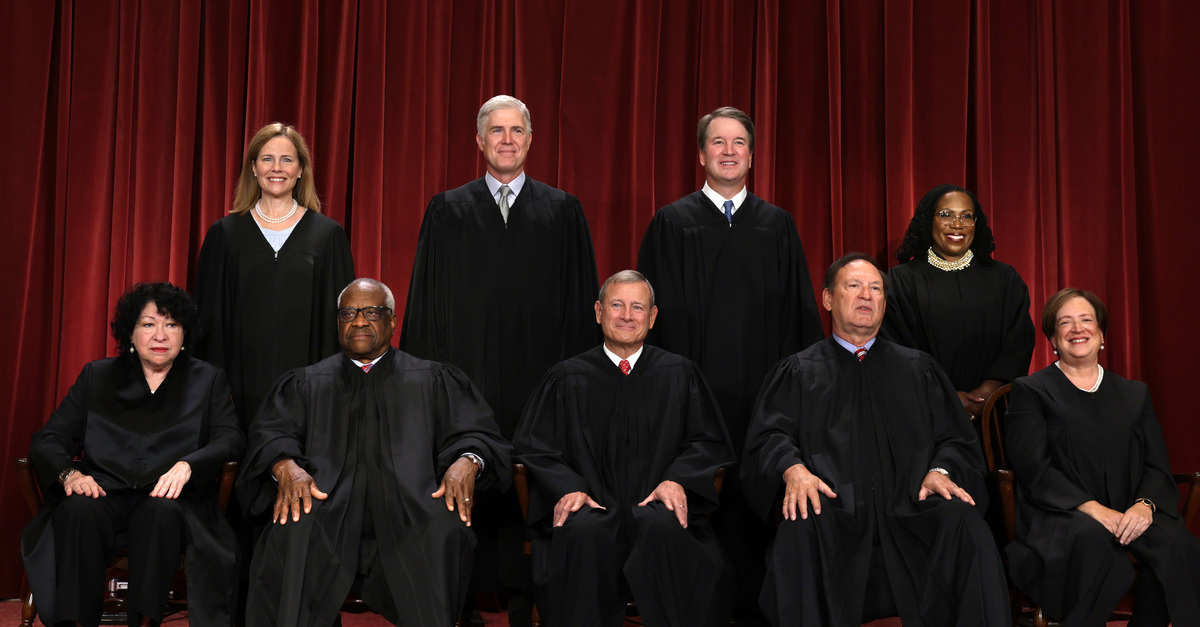

United States Supreme Court (front row L-R) Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan, (back row L-R) Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

The justices heard oral arguments Tuesday in U.S. ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources, an unusual case in which a doctor-turned-whistleblower is fighting for his right to “sue on behalf of the King” and for himself.

Here’s what that all means.

Jesse Polansky is a physician who worked for two months as an advisor for Executive Health Resources (EHR), a company that certifies health care billing for Medicare submissions to the government. Polansky suspected that EHR was allowing providers to over-bill Medicare by unnecessarily certifying certain services for inpatient treatment when the patients were not qualified.

Under the federal False Claims Act (“FCA”), whistleblowers like Polansky are allowed to bring lawsuits called “qui tam actions” against wrongdoers. “Qui tam” is a shortening of the Latin phrase meaning “Who sues on behalf of the King as well as for himself”; in these lawsuits, private plaintiffs are permitted to bring fraud lawsuits under the FCA in the name of the U.S. government. Then, if the plaintiffs (who are known as “relators” in this context) prevail, they are entitled to a share of the judgment against the fraudster. Meanwhile, qui tam lawsuits are not typical private lawsuits in that the federal government retains certain rights of its own — including the right to take over for the private plaintiff or to dismiss the lawsuit.

The case before the justices tests the limits of those rights retained by the federal government.

Polansky filed his qui tam suit against EHR in 2012. The federal government investigated Polansky’s claims, but ultimately decided not to participate in the lawsuit. Polansky continued the costly litigation on his own for five years, which required the government to participate in the discovery process. Then, the Department of Justice (DOJ) moved to dismiss the case on the grounds that providing documents to support the litigation was too burdensome and that it did not believe Polansky would win the case.

The district court granted the government’s motion to dismiss and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit again sided with the DOJ on appeal. Other circuits have developed different standards, however, for when the government may dismiss a qui tam action over the objection of the relator.

The dispute is particularly notable in that it creates a strange bedfellows situation: the DOJ is aligned with the fraud defendants themselves. The dispute is set against the backdrop of the larger picture of whistleblower actions, which are becoming an increasingly important tool for the enforcement of federal laws including the FCA. A ruling in favor of the government’s position in the Polansky case would seriously reduce the power of whistleblowers in future FCA cases.

Attorney Daniel Geyser faced a moderately skeptical bench as he presented his arguments on Polansky’s behalf. For the most part, the justices confined their questions to inquiries about how the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure — or some other “textual hook,” as Justice Clarence Thomas phrased it — would support Geyser’s argument.

Assistant to the Solicitor General Frederick Liu argued on behalf of the DOJ that the plain text of the FCA easily resolves the case in favor of the federal government. According to Liu’s argument, qui tam actions are an assignment of the government’s interest as opposed an interest that belongs to the claimant relator.

Justice Samuel Alito pressed Liu on the limits of the DOJ’s power to legally dismiss the case.

“What if the United States dismissed because they consulted an astrologer?” asked Alito.

Liu responded that astrology would form a basis that would meet the high “arbitrary and capricious” bar for disallowing a dismissal imposed by the FCA.

Alito next asked Liu about a situation in which the federal government might put a whistleblower in a difficult position:

What happens when the government belatedly intervenes or moves to dismiss and doesn’t really have a good reason for having waited, but by that time, the relator has spent a ton of money litigating the case. Is it just too bad for the relator?

Liu responded that, “It is too bad,” and noted that relators bring their cases knowing that the government might exercise their dismissal right even after significant effort has been spent litigating the case.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor picked up on a line of questioning that had also been raised by Alito: What would happen if the federal government chose to dismiss the case simply because there was political pressure to do so?

“Is that good enough?” Sotomayor asked.

“It would truly depend on the circumstances of the case,” Liu responded.

During the 90 minutes of oral arguments, the justices never focused their inquiries on Polansky, or about the practical outcome of his lawsuit. Rather, the focus was on potential for the DOJ to wreak havoc in future cases, as well as for the hunt for a statutory basis in which to ground arguments on behalf of qui tam claimants more broadly.

You can listen to the full oral arguments here.

[image via Alex Wong/Getty Images]