The currently 8-justice U.S. Supreme Court agreed on Friday to hear oral arguments in consolidated cases that some fear will lead a burgeoning conservative majority to dramatically weaken Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). The cases are Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, and Arizona Republican Party v. Democratic National Committee.

As Bloomberg News Supreme Court reporter Greg Stohr noted, this sets up a “post-election clash that could further weaken the Voting Rights Act,” as SCOTUS “will rule on Arizona policies governing out-of-precinct voting, third-party ballot collection.”

Stohr predicted that oral arguments will occur in January.

Section 2 of the VRA, the Department of Justice helpfully notes, “prohibits voting practices or procedures that discriminate on the basis of race, color, or membership in one of the language minority groups identified in Section 4(f)(2) of the Act.”

“Most of the cases arising under Section 2 since its enactment involved challenges to at-large election schemes, but the section’s prohibition against discrimination in voting applies nationwide to any voting standard, practice, or procedure that results in the denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority group,” the DOJ says. “Section 2 is permanent and has no expiration date as do certain other provisions of the Voting Rights Act.

Here’s what Section 2 itself says [emphasis ours]:

(2) No person acting under color of law shall—

(A) in determining whether any individual is qualified under State law or laws to vote in any election, apply any standard, practice, or procedure different from the standards, practices, or procedures applied under such law or laws to other individuals within the same county, parish, or similar political subdivision who have been found by State officials to be qualified to vote;

(B) deny the right of any individual to vote in any election because of an error or omission on any record or paper relating to any application, registration, or other act requisite to voting, if such error or omission is not material in determining whether such individual is qualified under State law to vote in such election; or

(C) employ any literacy test as a qualification for voting in any election unless (i) such test is administered to each individual and is conducted wholly in writing, and (ii) a certified copy of the test and of the answers given by the individual is furnished to him within twenty-five days of the submission of his request made within the period of time during which records and papers are required to be retained and preserved pursuant to title III of the Civil Rights Act of 1960 [52 U.S.C. 20701 et seq.]: Provided, however, That the Attorney General may enter into agreements with appropriate State or local authorities that preparation, conduct, and maintenance of such tests in accordance with the provisions of applicable State or local law, including such special provisions as are necessary in the preparation, conduct, and maintenance of such tests for persons who are blind or otherwise physically handicapped, meet the purposes of this subparagraph and constitute compliance therewith.

Arizona’s Republican Attorney General Mark Brnovich petitioned for certiorari back in April 2020, seeking to resolve questions about the state’s election integrity rules—namely, “an ‘out-of- precinct policy,’ which does not count provisional ballots cast in person on Election Day outside of the voter’s designated precinct, and a ‘ballot-collection law,’ known as H.B. 2023, which permits only certain persons (i.e., family and household members, caregivers, mail carriers, and elections officials) to handle another person’s completed early ballot.”

“A majority of States require in-precinct voting, and about twenty States limit ballot collection,” the petition said.

Democrats argued that the rules existed precisely to suppress the minority vote.

The district court and a three-judge panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld the policies “under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and the Fifteenth Amendment,” but then the full Ninth Circuit reheard the matter and the majority reversed course—finding that “Arizona’s policy of wholly discarding, rather than counting or partially counting, out-of-precinct ballots, and (a state law’s) criminalization of the collection of another person’s ballot, have a discriminatory impact on American Indian, Hispanic, and African American voters in Arizona.”

Brnovich wants the Supreme Court to answer two questions:

1. Does Arizona’s out-of-precinct policy violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act?

2. Does Arizona’s ballot-collection law violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act or the Fifteenth Amendment?

Arizona Republican Party v. Democratic National Committee, citing the Ninth Circuit decision in an April 2020 petition for cert of its own, similarly sought to learn whether Section 2 of the VRA “compels states to authorize any voting practice that would be used disproportionately by racial minorities, even if existing voting procedures are race-neutral and offer all voters an equal opportunity to vote.”

The second question that petitioner wants answered is whether the Ninth Circuit “correctly held that Arizona’s ballot-harvesting prohibition was tainted by discriminatory intent even though the legislators were admittedly driven by partisan interests and by supposedly ‘unfounded’ concerns about voter fraud.”

Rick Hasen, an election law expert and Professor of Law and Political Science at UC Irvine, responded to the SCOTUS news by saying he believes the high court took up the cases “because Arizona was found to have committed intentional race discrimination against minority voters.”

“If they reverse that, it would not necessarily undermine the rest of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,” Hasen predicted.

Others were not so optimistic. Slate legal writer Mark Joseph Stern immediately predicted, in exceedingly dire terms, that “conservatives could use [the case] to end the Voting Rights Act as we know it.”

“After SCOTUS gutted preclearance in Shelby County v. Holder, the VRA’s ‘effects test’—which prohibits laws that have a racist effect, even if they weren’t clearly motivated by racism—emerged as a somewhat effective shield against voter suppression,” he added. “Now SCOTUS may eviscerate it.”

Stern then said he had little doubt the presumably imminent 6-3 conservative majority means certain doom for the landmark civil rights law.

“The Supreme Court just raised the stakes. If a 6–3 conservative majority decides this case, it will, in all likelihood, effectively repeal the remnants of the Voting Rights Act. Congress can either add justices or say goodbye to the most important civil rights law in history,” Stern said. “I have dreaded a frontal attack on Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act for so many years. Now it is here, under the worst possible circumstances, with a looming 6–3 SCOTUS majority ready to rip the remainder of the law to shreds. This is really bad news. It’s frankly terrifying.”

Civil rights lawyer Sasha Samberg-Champion, a member of the DOJ during the Obama administration, similarly predicted serious and wide-ranging consequences.

https://twitter.com/ssamcham/status/1312035124486246402?s=20

“And the ripple effects from SCOTUS’s review of the VRA’s effects test could extend to disparate impact law more generally. This immediately becomes one of the major civil rights cases of the term,” he said.

Leah Litman, an Assistant Professor of Law at Michigan Law School, responded with an I Told You So.

https://twitter.com/LeahLitman/status/1312023801270501377?s=20

“Note: your friendly neighborhood CASSANDRAS, @ProfMMurray and I, warned that a further weakening of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act would be one consequence of a 6-3 conservative court,” Litman said.

https://twitter.com/LeahLitman/status/1312024200970932224?s=20

“*[S]erious SCOTUS Justice voice*: weakening and/or eliminating Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act is … necessary to enforce the voting rights act,” Litman snarked with apparent seriousness about how current-SCOTUS-plus-future-Justice Amy Coney Barrett might rule.

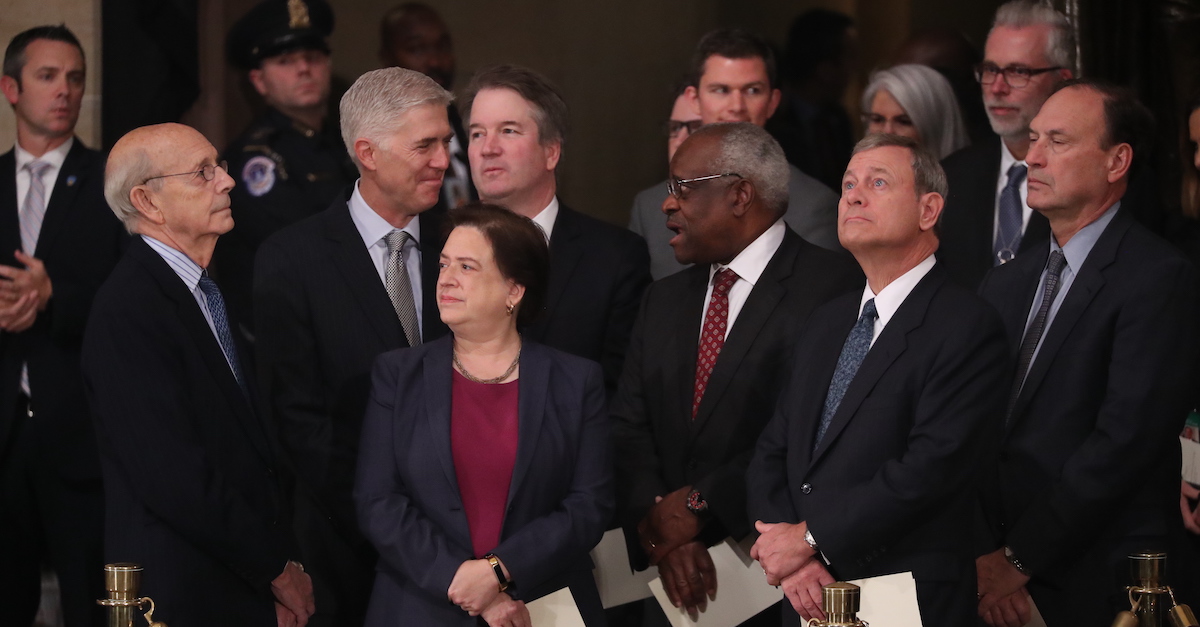

[Image via Jonathan Ernst – Pool/Getty Images]