The U.S. Supreme Court once again waded into legal territory involving what is typically one of its most contested subjects: the human uterus. But this time, the case wasn’t about abortion.

The case Minerva Surgical Inc. v. Hologic Inc. concerns a patent dispute between the inventor of a device used to treat abnormal uterine bleeding–bleeding that occurs outside of a woman’s monthly period–and the company to which the device, and the device’s patent rights, were originally sold and assigned.

Unlike other Supreme Court cases involving female reproductive care, the medical devices themselves are decidedly uncontroversial—except, perhaps, to patent lawyers and nine justices who split 5-4 on the ruling.

Csaba Truckai invented the NovaSure System in the late 1990s and later received a patent. That invention used a moisture-permeable applicator head to target certain unwanted cells in the lining of the uterus. The NovaSure patent was quickly assigned to Truckai’s company Novacept. Eventually, after a series of sales and buyouts, the patent rights to NovaSure were acquired by Hologic.

In 2008, Truckai started another company–Minerva–and invented a similar anti-uterine-bleeding device called the Minerva Endometrial Ablation System. This device does more or less the same thing as the original but with a small and maybe notable difference.

In a 5-4 majority opinion cutting across partisan lines, Justice Elena Kagan explains the backstory:

Not through with inventing, Truckai founded in 2008 petitioner Minerva Surgical, Inc. There, he developed a supposedly improved device to treat abnormal uterine bleeding. Called the Minerva Endometrial Ablation System, the device (like the NovaSure System) uses an applicator head to remove cells in the uterine lining. But the new device, relying on a different way to avoid unwanted ablation, is “moisture impermeable”: It does not remove any fluid during treatment. The PTO issued a patent for the device, and in 2015 the FDA approved it for commercial sale.

Also, in 2015, and, as the majority opinion notes “[a]ware of Truckai’s activities,” Hologic filed a patent continuation application that encompassed “applicator heads generally, without regard to whether they are moisture permeable” and the government signed off on that request. Hologic subsequently sued Minerva for patent infringement.

Two courts–district and appellate–ruled in Hologic’s favor.

Minerva denied infringing on Hologic’s patent. More importantly, the company also argued that Hologic’s patent was never enforceable in the first place. And in doing so, sought to revoke the entire legal doctrine known as “patent assignor estoppel.”

Though thrice replete with legalese, the doctrine is easily encapsulated by the facts of the case here: patent assignor estoppel simply means that once a patent (like NovaSure) is assigned, the inventor/assignee (such as Truckai) doesn’t get to go back and challenge the validity of that assignment (to Hologic) after they’ve made their money (some $8 million for Truckai) selling away those limited-time monopoly rights.

And that’s exactly how five of the nine justices saw things–with some reservations.

“Assignor estoppel, we now hold, is well grounded in centuries-old fairness principles, and the [appeals court] was right to uphold it,” the majority notes. “But the [appellate] court failed to recognize the doctrine’s proper limits. The equitable basis of assignor estoppel defines its scope: The doctrine applies only when an inventor says one thing (explicitly or implicitly) in assigning a patent and the opposite in litigating against the patent’s owner.”

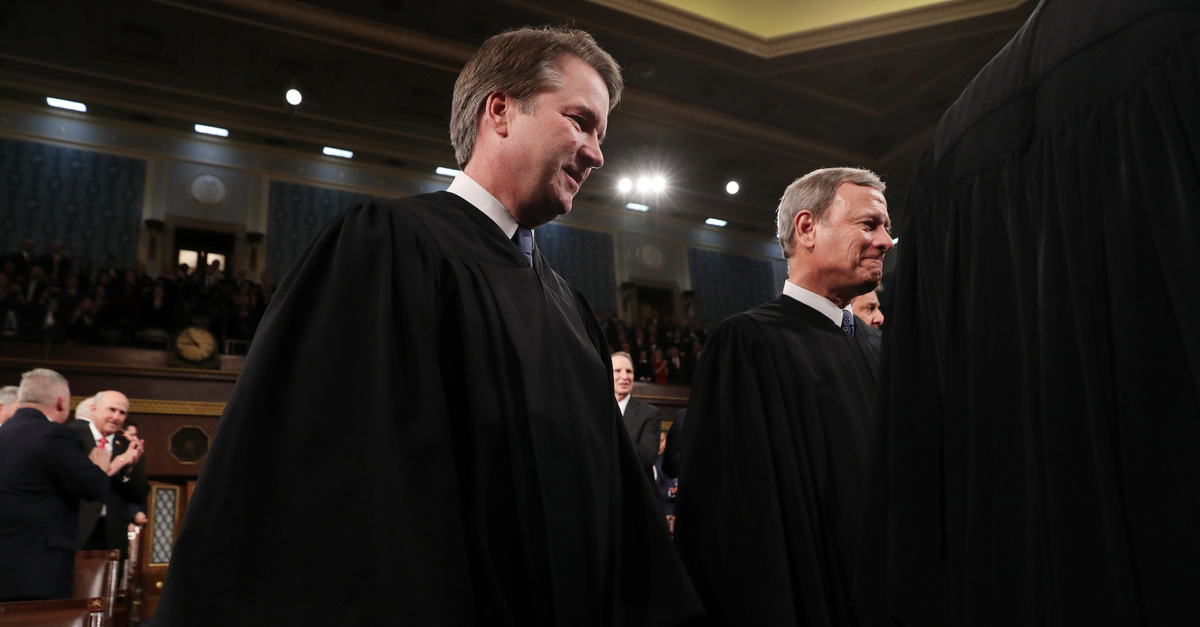

Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Steven Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Brett Kavanaugh joined in the opinion, where Kagan goes on to elaborate [emphasis added]:

This Court recognized assignor estoppel a century ago, and we reaffirm that judgment today. But as the Court recognized from the beginning, the doctrine is not limitless. Its boundaries reflect its equitable basis: to prevent an assignor from warranting one thing and later alleging another. Assignor estoppel applies when an invalidity defense in an infringement suit conflicts with an explicit or implicit representation made in assigning patent rights. But absent that kind of inconsistency, an invalidity defense raises no concern of fair dealing—so assignor estoppel has no place.

In other words, the nation’s high court upheld the doctrine itself but said that the appeals court failed to properly consider whether the patent continuation application filed by Hologic was actually protected by the doctrine because it may have been “materially broader” than the originally (and validly) assigned claim.

“In Truckai’s view, the new claim expanded on the old by covering non-moisture-permeable applicator heads,” the court notes. “In Hologic’s view, the claim matched a prior one that Truckai had assigned. Resolution of that issue in light of all relevant evidence will determine whether Truckai’s representations in making the assignment conflict with his later invalidity defense—and so will determine whether assignor estoppel applies.”

In two separate dissents, four justices argued that the majority’s findings do not square with a nearly century-old precedent: the 1924 case of Westinghouse Elec. & Mfg. Co. v. Formica Ins. Co., which implicitly approved of the doctrine of assignor estoppel.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote one of those dissents, which Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch joined. Justice Samuel Alito dissented separately to question whether Westinghouse should be overturned.

[image via Leah Millis-Pool/Getty Images]