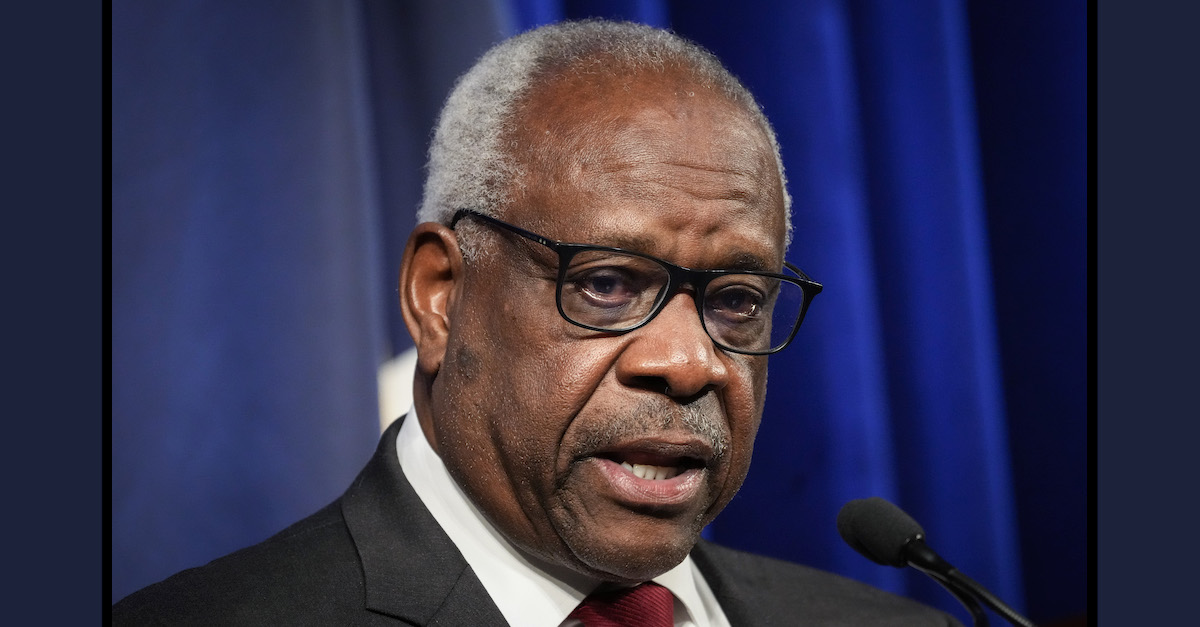

Associate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas speaks at the Heritage Foundation on October 21, 2021 in Washington, D.C.

The Supreme Court of the United States ruled 6-3 in a fractured opinion Wednesday in Egbert v. Boule, a case from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit about a federal agent’s alleged mistreatment of a bed-and-breakfast owner. The case was the latest attempt to create an “extension” of allowable “Bivens claims” in which individuals may sue federal actors for violations of constitutional rights.

U.S. citizen Robert Boule is the owner of the “Smuggler’s Inn” in Blaine, Washington — a town near the Canadian border. The Smuggler’s Inn has long been known to law enforcement as a potential site of illegal border crossings. As the Court mentioned in a footnote in its decision, Boule was recently convicted in Canadian court for engaging in human trafficking after pleading guilty to trafficking 11 Afghanis and Syrians into Canada. Boule has also worked as an informant for the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The claims Boule sought to bring against the federal government stemmed from an altercation between U.S. Border Patrol agent Erik Egbert and Boule in 2014. Egbert had heard that a suspicious guest was due to fly in from Turkey and check into the Smuggler’s Inn. Egbert, who did not have a warrant, drove to the inn and waited.

When the guest arrived, Egbert entered Boule’s private driveway and attempted an interception. Boule asked Egbert to leave, but Ebert refused, and the confrontation became physical. Boule refused to move away from Egbert’s car, and Egbert grabbed him and pushed him onto the ground.

Egbert ultimately concluded that the guest was lawfully present in the United States. Boule, however, complained about Egbert’s actions to a supervisor and later sought medical attention for back injuries he said he suffered as a result of the incident. Egbert then allegedly retaliated against Boule in a number of ways, including calling the Internal Revenue Service and asking the agency to perform a tax audit on Boule. According to Boule, compliance with the audit cost him $5,000 in accounting fees, and the audit itself yielded no evidence of wrongdoing on Boule’s part.

Boule waged a federal lawsuit claiming that Egbert violated both his Fourth and First Amendment rights. The claims, known as “Bivens claims,” are federal analogs to a 42 U.S. Code § 1983 civil rights action against state actors. They require that a plaintiff either assert an established set of rights that were violated — or that a court allow an “extension” of allowable Bivens claims. The name of these claims is derived from the 1971 SCOTUS case Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents, in which SCOTUS found an implied cause of action against federal officials who violate constitutional rights.

Justice Clarence Thomas began the Court’s 17-page opinion by reminding readers that the high court has consistently (indeed, 11 times over the past 42 years) declined to extend Bivens. Primarily, Thomas and the majority rested their holding on the special nature of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents’ work. The Court reasoned that because CBP handles cases involving national security risks, Egbert’s actions fall outside the scope of Bivens‘ reach.

Thomas included the photo below in his opinion to underscore his observation that “any person could easily enter the United States or Canada through or near Boule’s property.” The justice expounded on the inn’s history of cross-border smuggling of everything from people to myriad drugs to money to “items of significance to criminal organizations.”

The location of the Smuggler’s Inn is shown.

Thomas, clearly no fan of Boule’s, detailed, “Ever the entrepreneur, Boule saw his relationship with Border Patrol as a business opportunity.” According to Thomas, Boule would host unlawful entrants at his inn, then charge for shuttle service as he drove them around while simultaneously informing Border Patrol about anyone of interest.

Thomas explained the incident between Boule and Egbert as a tale born of good law enforcement. When Boule told Border Patrol about a Turkish national, “Agent Egbert grew suspicious, as he could think of ‘no legitimate reason a person would travel from Turkey to stay at a rundown bed-and-breakfast on the border in Blaine.'” Thomas included the photo below of the accommodations at the Smuggler’s Inn to emphasize the reasonableness of Egbert’s suspicion.

A bedroom at the Smuggler’s Inn is shown.

Thomas then warned against judiciary overreach. Allowing Bivens actions in new categories should be a “disfavored judicial activity,” Thomas said, and argued that Congress is the appropriate entity to do so. The justice held fast to his message of judicial restraint, and wrote, “Congress is better positioned to create remedies in the border-security context, and the Government already has provided alternative remedies that protect plaintiffs like Boule.”

Thomas rejected the claim that Egbert’s actions as a CBP agent should be treated the same as any other law enforcement officer. Rather, Thomas reasoned, CBP’s work has national security implications, rendering its officers’ actions distinct from those of a typical police officer. Thomas wrote at length about the recent Hernandez case, in which SCOTUS similarly refused to extend the right to file a Bivens action to the parents of a Mexican child fatally shot by CBP at the U.S.-Mexico border; the ruling in the Boule case, said Thomas, should fall in line with the one in Hernandez.

The majority’s second bit of reasoning—that a Bivens action simply isn’t needed in this case—had been anticipated by Boule’s counsel. Boule’s argument was that the grievance process within CBP is inadequate, because it does not allow him to participate as a party. Thomas dismissed this point out of hand, and wrote, “we have never held that a Bivens alternative must afford rights to participation or appeal.” Rather, Thomas said, the goal is simply to deter unconstitutional acts of individual officers. “So long as Congress or the Executive has created a remedial process that it finds sufficient to secure an adequate level of deterrence, the courts cannot second-guess that calibration by superimposing a Bivens remedy,” Thomas wrote.

Thomas also rejected Boule’s claim of a Bivens action based on deprivation of First Amendment rights. His reasoning was much the same as it was for Boule’s Fourth Amendment claim:

Now presented with the question whether to extend Bivens to this context, we hold that there is no Bivens action for First Amendment retaliation. There are many reasons to think that Congress, not the courts, is better suited to authorize such a damages remedy.

Justice Neil Gorsuch penned his own brief concurrence, in which he stressed the importance of separation of powers and called out the Bivens case itself for being “a misstep.” Gorsuch wrote that he “struggle[s] to see how [the Boule] facts differ[] meaningfully from those in Bivens itself,” given that both raise constitutional violations committed by federal law enforcement officers. To Thomas’ point that CBP’s work raises unique immigration concerns, Gorsuch asked: “But why does that matter?”

Gorsuch pushed the majority’s analysis a step farther, and argued that if the analysis applicable to new Bivens actions always requires a contest of courts versus Congress, then Congress will always win. Therefore, wrote Gorsuch, “In fairness to future litigants and our lower court colleagues, we should not hold out that kind of false hope, and in the process invite still more ‘protracted litigation destined to yield nothing.'”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote a partial dissent which was joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan. Sotomayor wrote that Wednesday’s decision in Boule, combined with recent precedent, enables SCOTUS to “close the door” not just to Boule’s claim, but also “to others that fall squarely within Bivens‘ ambit.”

Although Sotomayor agreed with the decision to reject Boule’s First Amendment claim, she would have allowed Boule’s action to proceed on his Fourth Amendment claim. Sotomayor’s take on the incident between Boule and Egbert was that it looked a lot like the facts of Bivens itself:

Boule’s Fourth Amendment claim does not arise in a new context. Bivens itself involved a U.S. citizen bringing a Fourth Amendment claim against individual, rank-and-file federal law enforcement officers who allegedly violated his constitutional rights within the United States by entering his property without a warrant and using excessive force. Those are precisely the facts of Boule’s complaint.

The only difference, argued Sotomayor, was that the offending officers worked for different federal agencies.

The dissenting justice, however, did find significant differences between the recent Hernandez case (on which the majority relied in its reasoning) and the Boule case. “This case […] does not present an ‘international incident’ that might affect diplomatic relations, unlike the cross-border killing of a foreign-national child,” Sotomayor wrote. She continued to explain that while some CBP agents—like those involved in the Hernandez case—are stationed at the border to prevent illegal entry, “Agent Egbert was not ‘attempting to prevent illegal entry’ or otherwise engaged in activities with a ‘strong connection to national security.'”

Sotomayor had harsh words for the majority’s analysis, which she said was “selectively quoting our precedents and presenting its newly announced standard as if it were always the rule.” She dismissed Thomas’ claims of national security interests afoot as “sheer hyperbole,” and noted that what was central to the Boule case was “physical assault by a federal officer against a U.S. citizen on U.S. soil.”

As for Congress’ role, Sotomayor was satisfied that Congress has spoken, in that it set out the rules for how immigration officers must act.

“Mere proximity to a border, in other words, did not give Agent Egbert greater license to enter Boule’s property,” she wrote, “Nor does it diminish or call into question the remedies for constitutional violations that a plaintiff may pursue, particularly where, as here, an agent unquestionably was not acting “for the purpose of patrolling the border to prevent the illegal entry of aliens into the United States.”

Sotomayor argued that the SCOTUS decision will put many at risk of rights violations by unscrupulous law enforcement officers.

“The consequences of the Court’s drive-by, categorical assertion will be severe,” she warned. “Absent intervention by Congress, CBP agents are now absolutely immunized from liability in any Bivens action for damages, no matter how egregious the misconduct or resultant injury.”

Sotomayor also had words of guidance for the lower courts. Despite what she called the Court’s “thinly veil[ed]… disapproval” of Bivens—and despite the Boule decision making it “harder for plaintiffs to bring a successful Bivens claim”—the justice insisted “the lower courts should not read it to render Bivens a dead letter.”

[Smuggler’s Inn images via SCOTUS, Image of Justice Thomas via Drew Angerer/Getty Images]