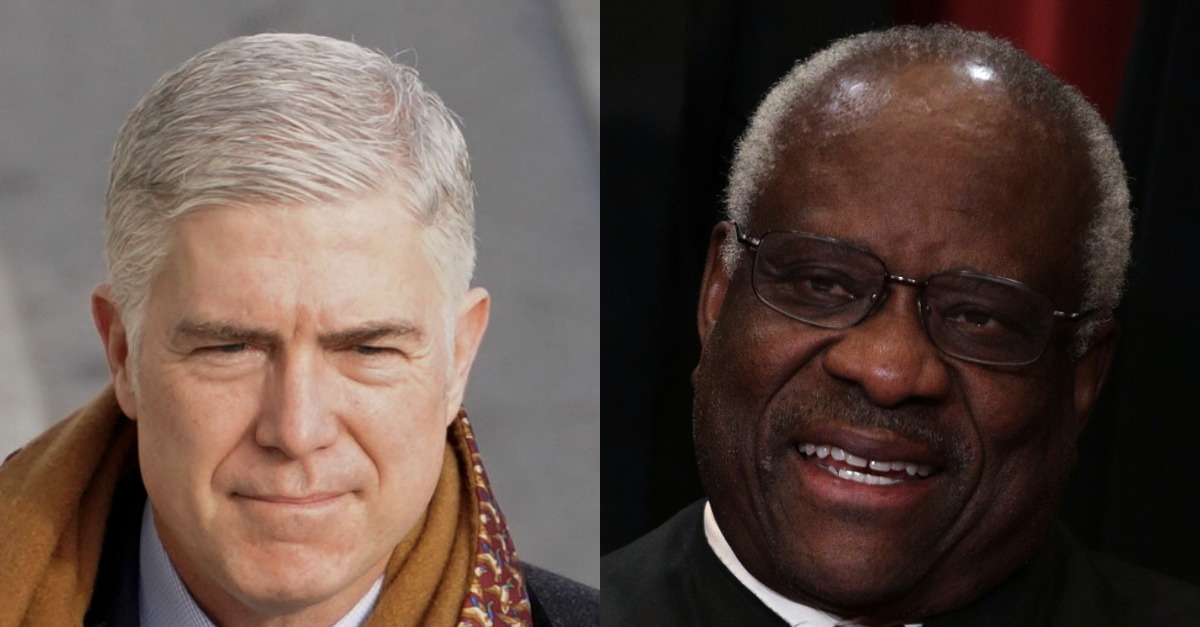

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to hear an appeal brought by former New York State Assembly speaker Sheldon Silver over several 2018 corruption charges. Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas would have heard the onetime Democratic Party power broker’s appeal–in an apparent bid for precedential clarity.

“Normally, extortion and bribery are treated as distinct crimes,” Gorsuch wrote in a brief dissent from the high court’s denial of certiorari. “In Evans v. United States, however, this Court conflated them for purposes of the Hobbs Act when a public official is the defendant. Chief Justice [William] Rehnquist and Justices [Antonin] Scalia, Thomas, and [Stephen] Breyer have all questioned that judgment. I would have granted this case to reconsider Evans in light of these thoughtful criticisms.”

In the decades-old Evans case, Thomas authored a lengthy and textualist-themed accusation that sought to upbraid the nation’s high court for over-expanding the definition of “extortion” far beyond the definition Congress intended when it passed the Hobbs Act of 1946.

From that Thomas classic of the genre [emphasis in original]:

What does it mean for an official to take money “by colour of his office”? The Court fails to address this question, simply assuming that common-law extortion encompassed any taking by a public official of something of value that he was not “due.”

The “under color of office” element of extortion, however, had a definite and well-established meaning at common law. “At common law it was essential that the money or property be obtained under color of office, that is, under the pretense that the officer was entitled thereto by virtue of his office. The money or thing received must have been claimed or accepted in right of office, and the person paying must have yielded to official authority.” Thus, although the Court purports to define official extortion under the Hobbs Act by reference to the common law, its definition bears scant resemblance to the common-law crime Congress presumably codified in 1946.

Thomas’s argument is that the federal court system, over the years and starting in the early 1970s, became a bit too friendly with, and reflexive to, the dictates of federal prosecutors by signing off on their wholesale investigations of public officials under the new rubric of “corruption.” This started with a Third Circuit case that essentially “obliterated the distinction between extortion and bribery” in order to create a court-sanctioned and, in Thomas’s view, whole-cloth “license for ferreting out all wrongdoing at the state and local level” by creating “a special code of integrity for public officials.”

All of that would be fine for the Congress to create, the conservative justices insisted, except this understanding was an intentional misreading of the statute at hand by the court itself.

Citing the arguments of conservative legal heavyweights Scalia and Rehnquist, Gorsuch apparently saw fit to lay down some of the still-extant lines when it comes to the Supreme Court’s capacious understanding of liability for elected officials under the Hobbs Act. But he also noted that liberal justice Breyer has also expressed very explicit reservations about conflating bribery and extortion into a catch-all for prosecutors to have carte blanche.

Breyer’s concurrence in Ocasio v. United States notes:

I agree with the sentiment expressed in the dissenting opinion of Justice Thomas that Evans v. United States, may well have been wrongly decided. I think it is an exceptionally difficult question whether “extortion” within the meaning of the Hobbs Act is really “the rough equivalent of . . . taking a bribe,” especially when we admittedly decided that question in that case without the benefit of full briefing on extortion’s common-law history.

In that much more recent 2016 case, however, Breyer ultimately agreed with the majority opinion. While expressing some doubt about the longevity and accuracy of Evans, he noted that it was still “good law” and therefore its wide latitude still prevailed when considering the application of the Hobbs Act to officials on the public dime.

The high court’s conservatives, by and large, and Thomas especially, have always been much more aggressive than their liberal counterparts when seeking to overturn precedent and correct what they see as flawed former decisions. So, Breyer’s slight misgivings were enough to form some middling dicta back in 2016–but they now appear to have fallen by the wayside when it comes to reassessing the scope of the Hobbs Act viz. Evans–or, it could be that Breyer didn’t think Silver’s particular case, a high-profile fall from power that shook the New York Democratic Party machine to its core–was worth the effort to claw back the prosecutorial playbook.

Silver was sacked as speaker in early 2015 after being arrested on seven corruption charges–only two weeks after Tammany Hall Democrats in Albany all-but unanimously voiced their support for their leader amidst a federal criminal investigation. He was originally convicted on those same charges later that year. An appeals court tossed the verdict but he was retried and convicted again in 2018. Three of those convictions, based on asbestos-related kickbacks, were then tossed on appeal. Four of the convictions, based on the time-honored New York tradition of real estate development kickbacks, were sustained.

Silver, currently serving a 6.5 year prison sentence, was rumored to have been considered for a pardon by former President Donald Trump, but that decision was reportedly shelved at the last minute.

[image via Melina Mara – Pool/Getty Images; Alex Wong/Getty Images]