In a move that may only embolden Republicans in their efforts to confirm Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court as soon as possible, SCOTUS declined to lift an injunction against the Trump administration’s restriction on the use of the abortion drug RU-486 (mifepristone) during the pandemic. Conservative Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas were not pleased with the high court’s punt, suggesting SCOTUS was permitting a U.S. District judge’s use of the pandemic “as a ground for expanding the abortion right recognized in Roe v. Wade.”

Plaintiffs, coalition of doctors and academic gynecologists, originally filed a lawsuit over the Food and Drug Administration rule requiring patients in need of mifepristone to pick their prescription up at a physical location dedicated to medicine–like a doctor’s office or hospital–and to sign a form. Such treatment of the drug, the plaintiffs argued, ran counter to generalized FDA guidance seeking to limit in-person clinical visits amid the pandemic.

The plaintiffs convinced Theodore D. Chuang, a Barack Obama-appointed federal judge in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland, to stop the FDA from enforcing the disparate treatment of mifepristone during the pandemic.

The trial judge found that the plaintiffs were likely to win on the merits of their claim that requiring “unnecessary in-person visits” to obtain the drug during the public health crisis imposes an “undue burden” on the constitutional right to an abortion and that the FDA’s treatment of mifepristone was therefore unconstitutional.

The district court also found that “absent an injunction,” the medical professional plaintiffs and their patients–who are primarily low-income people of color–would suffer irreparable harm.

In late August, the Trump administration filed an emergency petition with Chief Justice John Roberts requesting a stay of the district court’s order while the lawsuit makes its way through the court system. The Supreme Court denied that petition for a stay on Thursday.

“The Government sought a stay of an injunction preventing the Food and Drug Administration from enforcing in-person dispensation requirements for the drug mifepristone during the pendency of the public health emergency. The Government argues that, at a minimum, the injunction is overly broad in scope, given that it applies nationwide and for an indefinite duration regardless of the improving conditions in any individual State,” the high court said in brief. “Without indicating this Court’s views on the merits of the District Court’s order or injunction, a more comprehensive record would aid this Court’s review.”

“The Court will therefore hold the Government’s application in abeyance to permit the District Court to promptly consider a motion by the Government to dissolve, modify, or stay the injunction, including on the ground that relevant circumstances have changed,” the court continued. SCOTUS gave the District Court 40 days to do so.

Justice Alito dissented and Justice Thomas joined Alito.

“Six weeks have passed since the application was submitted, but the Court refuses to rule. Instead, it defers any action until the Government moves in the District Court to modify the injunction and the District Court rules on that motion, a process that may take another six weeks or more,” Alito began. “There is no legally sound reason for this unusual disposition.”

Alito then suggested that SCOTUS’s inaction on the issue was tantamount to giving credence to Judge Chuang’s unilateral expansion of abortion rights—even as the Court “stood by” and watched during the pandemic when the “free exercise of religion […] suffered previously un-imaginable restraints”:

In the present case, however, the District Court took a strikingly different approach. While COVID–19 has provided the ground for restrictions on First Amendment rights, the District Court saw the pandemic as a ground for expanding the abortion right recognized in Roe v. Wade, 410 U. S. 113 (1973). At issue is a requirement adopted by the FDA for the purpose of protecting the health of women who wish to obtain an abortion by ingesting certain medications, specifically, mifepristone and misoprostol. Under that requirement, a woman must receive a mifepristone tablet in person at a hospital, clinic, or medical office. Electronic Court Filing in No. 8:20–cv–01320, Doc. 1–4 (D Md., May 27, 2020), p. 3. The FDA first adopted the requirement in 2000, and then included it in a package of safety require- ments under express statutory authority in 2007. See 21 U. S. C. §355–1(f )(3)(C). Over the course of four presidential administrations, the FDA has enforced this requirement and has not found it appropriate to remove it. During the COVID–19 pandemic, the FDA suspended in-person dispensing requirements for some drugs, but it evidently decided that the mifepristone requirement should remain in force.

Alito directly criticized the trial judge for taking it “upon himself to overrule the FDA on a question of drug safety,” disregarding Chief Justice Roberts’s “admonition against judicial second-guessing of officials with public health responsibilities […].”

Alito all but said it was absurd that the trial judge said the restrictions constituted an “undue burden” when he was “apparently was not troubled by the fact that those responsible for public health in Maryland thought it safe for women (and men) to leave the house and engage in numerous activities that present at least as much risk as visiting a clinic—such as indoor restaurant dining, visiting hair salons and barber shops, all sorts of retail establishments, gyms and other indoor exercise facilities, nail salons, youth sports events, and, of course, the State’s casinos.”

“And the judge made the injunction applicable throughout the country, including in locales with very low infection rates and limited COVID–19 restrictions,” the justice went on. “Under the approach recently taken by the Court in cases involving restrictions on First Amendment rights, the proper disposition of the Government’s stay application should be clear: grant. But the Court is not willing to do that. Nor is it willing to deny the application. I see no reason for refusing to rule.”

Alito said the stay should especially have been issued because the District Court decision is “likely to be reversed” upon review.

Colin Kalmbacher contributed to this report.

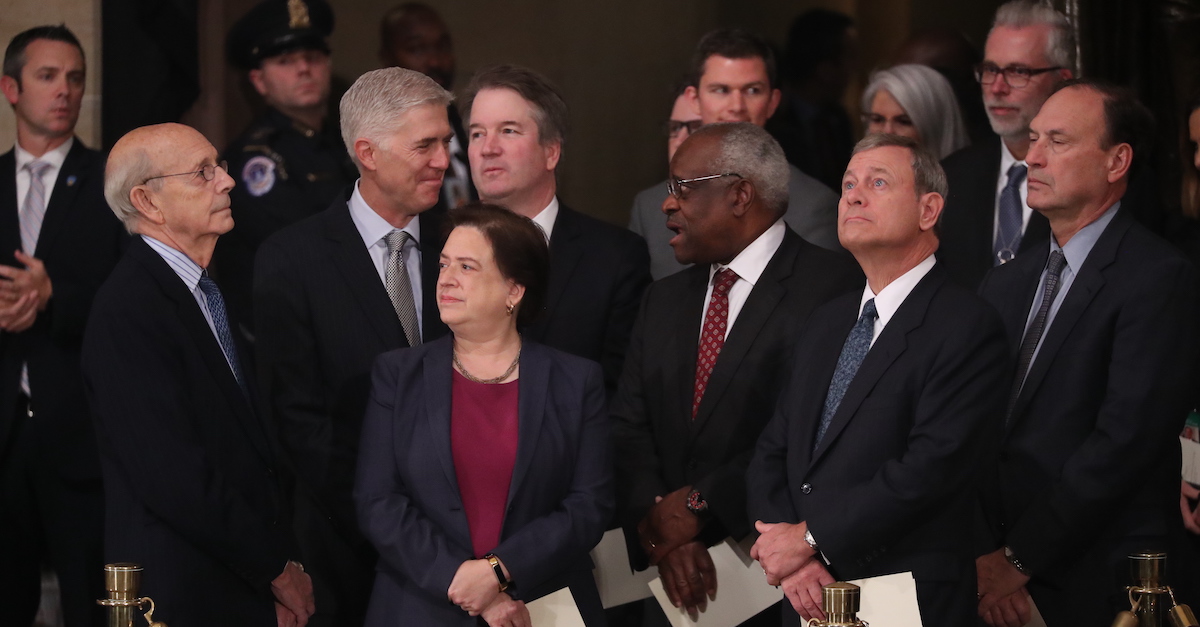

[image via Image SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images]