The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday issued an opinion in a high-profile criminal justice case that united the six-strong conservative majority against the three more liberal members of the bench.

In the case stylized as Edwards v. Vannoy, the high court found that the constitutional right to an unanimous jury trial is not retroactive. That right was only recently extended to the states in the Ramos ruling from April last year and several non-unanimous verdicts hung in the balance of Monday’s decision. Those verdicts will be allowed to stand; multiple prisoners in Louisiana and Oregon will still have to serve time under the old, recently-deemed-unconstitutional rules.

“The question in this case is whether the new rule of criminal procedure announced in Ramos applies retroactively to overturn final convictions on federal collateral review,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh notes. “Under this Court’s retroactivity precedents, the answer is no.”

The ruling makes short work of refusing to extend the Ramos right to previously convicted individuals by pointing out that the nation’s high court has steadfastly refused to apply similar such newfound procedural rights over the course of the past several decades.

“This Court has repeatedly stated that a decision announcing a new rule of criminal procedure ordinarily does not apply retroactively on federal collateral review,” Kavanaugh continues–before citing the relevant case that purports to allow for such retroactive application. “Indeed, in the 32 years since Teague underscored that principle, this Court has announced many important new rules of criminal procedure. But the Court has not applied any of those new rules retroactively on federal collateral review.”

The Teague case’s bearing on the court’s Monday decision is aptly described at the beginning of Justice Neil Gorsuch‘s concurrence:

Sometimes this Court leaves a door ajar and holds out the possibility that someone, someday might walk through it— though no one ever has or, in truth, ever will. In Teague v. Lane, 489 U. S. 288 (1989), the Court suggested that one day it might apply a new “watershed” rule of criminal procedure retroactively to undo a final state court conviction. But that day never came to pass. Instead, over the following three decades this Court denied “watershed” status to one rule after another. Rules guaranteeing individuals the right to confront their accusers. Rules ensuring that only a jury may decide a defendant’s fate in a death penalty case. Rules preventing racially motivated jury selection. All failed to win retroactive application. Today, the Court candidly admits what has been long apparent: Teague held out a “false hope” and the time has come to close its door.

In other words, the potential availability of retroactive application for criminal procedural rulings was little more than a rumor. In Vannoy, six of the nine justices decided to put that rumor to rest.

In terms of analysis, the inquiry here was not particularly elaborate or obtuse. The Kavanaugh-led court simply embraced Teague‘s conditional language that it was “unlikely” a new watershed right could be found in criminal procedure jurisprudence by flatly declaring that last year’s Ramos decision was not much of a watershed at all.

Practical considerations (like the prospect of undoing past convictions and forcing dozens of retrials) inform the heart of Kavanaugh’s ruling:

As the Court has explained, applying “constitutional rules not in existence at the time a conviction became final seriously undermines the principle of finality which is essential to the operation of our criminal justice system.” Here, for example, applying Ramos retroactively would potentially overturn decades of convictions obtained in reliance on [prior precedent]. Moreover, conducting scores of retrials years after the crimes occurred would require significant state resources. And a State may not be able to retry some defendants at all because of “lost evidence, faulty memory, and missing witnesses.” When previously convicted perpetrators of violent crimes go free merely because the evidence needed to conduct a retrial has become stale or is no longer available, the public suffers, as do the victims.

In dissent, Justice Elena Kagan argues that “the opinions in Ramos read as historic” due to the departure from stare decisis and because the court acknowledged that “the state laws countenancing non-unanimous verdicts originated in white supremacism and continued in our own time to have racially discriminatory effects.”

“Rarely does this Court make such a fundamental change in the rules thought necessary to ensure fair criminal process,” Kagan continues. “If you were scanning a thesaurus for a single word to describe the decision, you would stop when you came to ‘watershed.'”

The majority rejects Kagan’s logic and swats the dissent’s concerns away by noting that Gorsuch’s majority opinion in Ramos basically warned of Monday’s outcome in Vannoy.

“The lead opinion added that Teague is ‘demanding by design, expressly calibrated to address the reliance interests States have in the finality of their criminal judgments,'” the majority notes. “In light of that explicit language in Ramos, the Court’s decision today can hardly come as a surprise.”

Giving the dissent to Kagan in this case might read as something of a surprise, however, because she voted against the criminal defendant in Ramos–shocking many court watchers as she signed onto Justice Samuel Alito’s dissent that complained about the majority’s discussion of racism.

But Kagan takes the opportunity, in a footnote, to explain her prior vote publicly–an oddity among court opinions.

“I dissented in Ramos precisely because of its abandonment of stare decisis.” Kagan explains. “Now that Ramos is the law, stare decisis is on its side. I take the decision on its own terms, and give it all the consequence it deserves.”

To hear the dissent tell it, the majority has not only abandoned the watershed rule in Teague, they have abandoned “a core judicial rule: respect for precedent.”

Kavanaugh, on the other hand, takes Kagan to task for her prior vote in Ramos–a specific call-out and another oddity.

Again, the majority, at length:

[W]ith respect, JUSTICE KAGAN dissented in Ramos. To be sure, the dissent’s position on the jury-unanimity rule in Ramos was perfectly legitimate, as is the dissent’s position on retroactivity in today’s case. And it is of course fair for a dissent to vigorously critique the Court’s analysis. But it is another thing altogether to dissent in Ramos and then to turn around and impugn today’s majority for supposedly shortchanging criminal defendants. To properly assess the implications for criminal defendants, one should assess the implications of Ramos and today’s ruling together. And criminal defendants as a group are better off under Ramos and today’s decision, taken together, than they would have been if JUSTICE KAGAN’s dissenting view had prevailed in Ramos. If the dissent’s view had prevailed in Ramos, no defendant would ever be entitled to the jury-unanimity right—not on collateral review, not on direct review, and not in the future. By contrast, under the Court’s holdings in Ramos and this case, criminal defendants whose cases are still on direct review or whose cases arise in the future will have the benefit of the jury-unanimity right announced in Ramos. The rhetoric in today’s dissent is misdirected.

Kavanaugh further wrote that “no stare decisis values would be served by continuing to indulge the fiction that Teague’s purported watershed exception endures.”

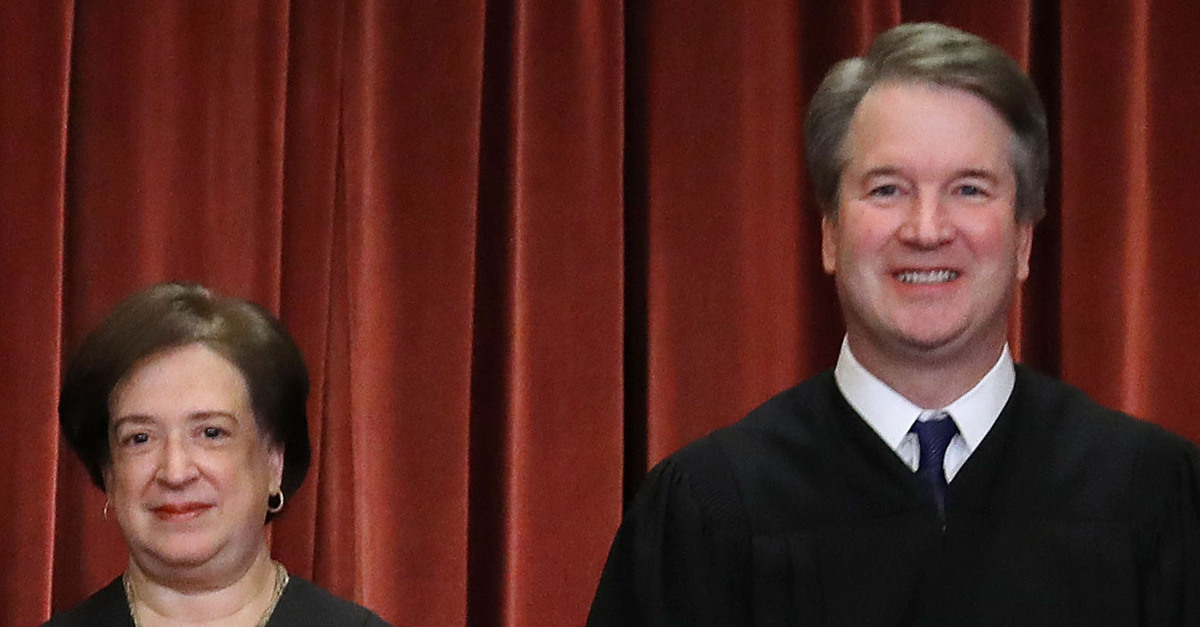

[image via Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images]