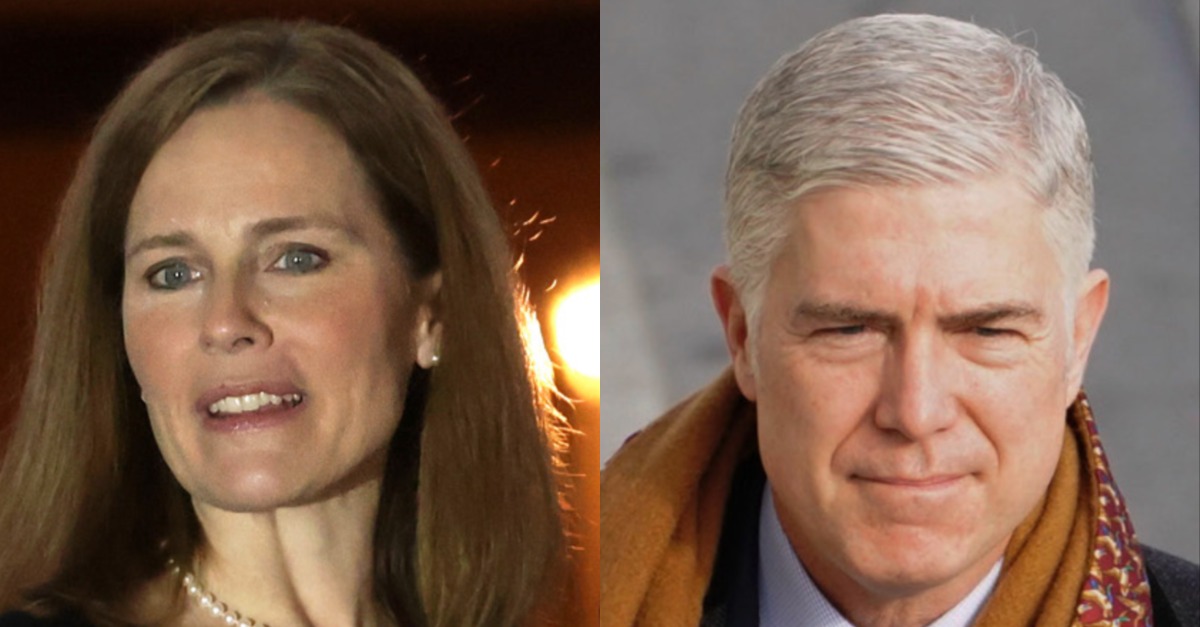

The Supreme Court of the United States denied certain military veterans a chance at greater retirement benefits in a nearly unanimous opinion authored by Justice Amy Coney Barrett on Thursday. Justice Neil Gorsuch bucked the 8-1 majority and would have allowed a subset of veterans to recoup more Social Security funds after their service ended.

Stylized as Babcock v. Kijakazi, the case turns on the Social Security Act’s so-called “windfall elimination provision,” which is a statute designed by Congress to reduce Social Security payments for retirees who receive separate pension payments. Such retirees would otherwise, in Congress’s view, receive a “windfall” from the Social Security Administration based on how the system originally counted earnings for workers in jobs exempt from Social Security taxes.

When amending the law, however, Congress exempted certain forms of pension payments from triggering the windfall exemption. One category of pensions given preferential treatment are described in statute as “a payment based wholly on service as a member of a uniformed service.” Or, put another way, Congress carved out a segment of law that allows some military veterans to receive “windfall” Social Security payments not accessible to the public.

But the exception clearly doesn’t cover all military veterans, and therein lies the controversy decided by the court.

The petitioner, David Babcock, worked for 33 years as a dual-status technician in the Michigan Army National Guard as a full time test pilot and pilot instructor. Completing the dual nature of his employment, he also mandatorily served as a member of the National Guard, where he performed training and drills. He eventually deployed to Iraq for a year.

“As its name suggests, this rare bird has characteristics of two different statuses,” Barrett explains. “On one hand, the dual-status technician is a ‘civilian employee’ engaged in ‘organizing, administering, instructing,’ ‘training,’ or ‘maintenance and repair of supplies’ to assist the National Guard. On the other, the technician ‘is required as a condition of that employment to maintain membership in the [National Guard]’ and must wear a uniform while working.”

The majority opinion goes on to explain how the dual-status nature of the federal fowl at issue works in terms of actual take home pay:

This dual role means that technicians perform work in two separate capacities that yield different forms of compensation. First, they work full time as technicians in a civilian capacity. For this work, they receive civil-service pay and, if hired before 1984, Civil Service Retirement System pension payments from the Office of Personnel Management. [A footnote helpfully points out that Civil Service pensions are now all-but extinct animals.] Second, they participate as National Guard members in part-time drills, training, and (sometimes) active-duty deployment. For this work, they receive military pay and pension payments from a different arm of the Federal Government, the Defense Finance and Accounting Service.

Babcock himself applied for Social Security benefits after retiring in 2009. He was granted the benefits by the SSA, but the agency decided the windfall exemption was triggered by his civilian pension and his payments were reduced by roughly $100 per month. He sued, arguing that his job as a dual-status technician for the National Guard should have entitled him to the uniformed service exemption. Several lower courts disagreed, and the nation’s high court took up the case in order to resolve a circuit split.

Justice Barrett described the question in the case in forthright terms: “The only question is whether Babcock’s civil-service pension for technician work avoids triggering the provision’s reduction in benefits because it falls within the exception for ‘a payment based wholly on service as a member of a uniformed service.'”

Most of the opinion’s argument is devoted to a discussion about what the word “as” means in the context of the statute–coming down on a textual, plain-meaning read of “[i]n the role, capacity, or function of.”

Dispensing with another argument about how the dual-status nature of his employment demands uniformed work for the National Guard, the court’s newest justice offered an analogy that she and most of her colleagues believed was the most apt for the facts of the case:

Nor are we moved by Babcock’s argument that the statutory requirement for technicians to maintain National Guard membership makes all of the work that they do count as Guard service. A condition of employment is not the same as the capacity in which one serves. If a private employer hired only moonlighting police officers to be security guards, one would not call that employment “service as a police officer.” So too here: the fact that the Government hires only National Guardsmen to be technicians does not erase the distinction between the two jobs.

Gorsuch, in his brief and lonely dissent, confesses “trepidation” for being the sole voice against the majority, but the justice said he “cannot help but find compelling the arguments advanced by the petitioner.”

The dissent’s logic is fairly straightforward, and, perhaps surprisingly, not really textual at all.

“Dual-status military technicians hold ‘a unique position in federal employment,'” he argues. “Not only do they sometimes serve on active duty, as the petitioner did. By statute, they spend the rest of their time working for the Guard — on matters ranging from training others to administration to equipment maintenance. At all times, they must ‘maintain membership’ in the National Guard and wear a Guard uniform while on the job. The authority to discharge or discipline these individuals, too, rests with the Adjutant General. Given these features of their employment, I would hold that dual-status technicians ‘serv[e] as’ members of the National Guard in all the work they perform for this country day in and day out.”

Gorsuch goes on to rubbish the moonlighting analogy:

[T]o my mind dual status technicians are more like part-time police officers employed in their outside hours by the same police department to train recruits, administer the precinct office, and repair squad cars — all on the condition that they wear their police uniforms and maintain their status as officers. I suspect most reasonable officers in that situation would consider the totality of their work to constitute “service as . . . member[s]” of the police force. So too here I expect most Guardsmen who serve as “dual-status technicians” — who come to work every day for the Guard, in a Guard uniform, and subject to Guard discipline — would consider all of their work to represent “service as . . . member[s]” of the National Guard. I would honor that reasonable understanding and would not curtail servicemembers’ Social Security benefits based primarily on implications extracted from other, separate “bookkeeping” statutes.

The majority directly addresses the uniform argument in conclusion — with a call-back to the text of the statute, perhaps a jab at the dissent for leaving the text behind.

“Determining whether Babcock’s technician employment was service ‘as’ a member of the National Guard does not turn on factors like whether he wore his uniform to work,” Barrett explains. “It turns on how Congress classified the job — and as already discussed, Congress classified dual-status technicians as ‘civilian.’ Babcock dismisses that distinction as one drawn for purposes of ‘administrative bookkeeping,’ but bookkeeping matters when it comes to pay and benefits.”

[images via Getty Images]