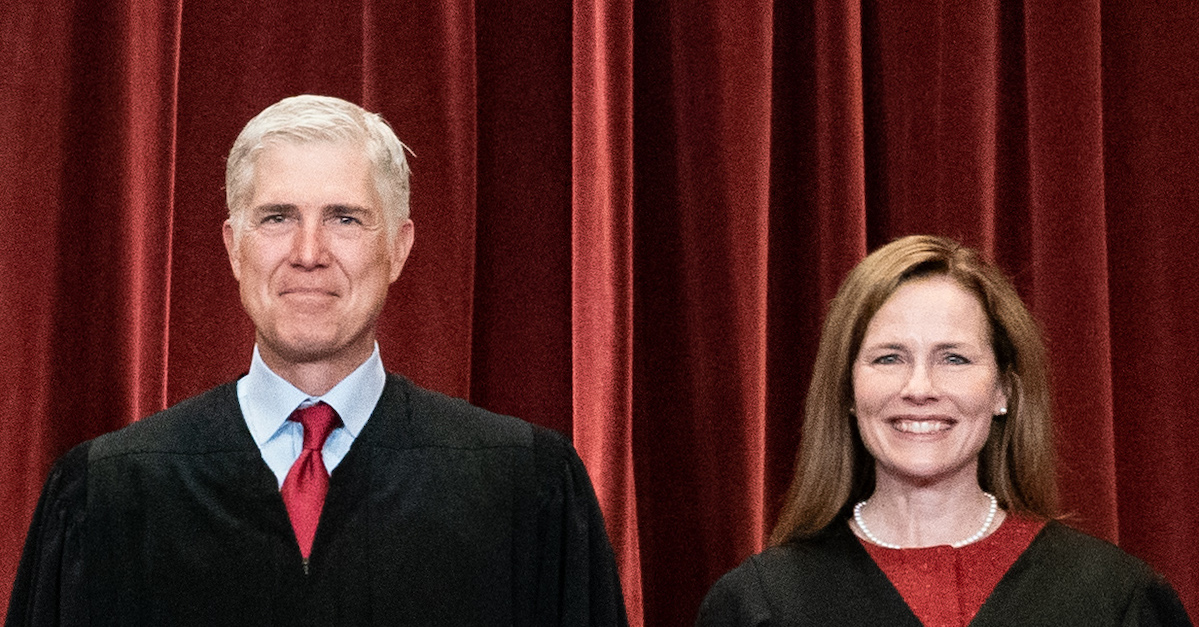

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch (left), Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett (right).

The Supreme Court of the United States ruled 6-3 that Navajo tribe member Merle Denezpi has no constitutional right to avoid successive prosecutions for the same incident. After Denezpi committed a sexual assault on tribal land, he was first prosecuted in the Court of Indian Offenses, then again later, in U.S. district court. He appealed, arguing that the successive prosecutions trigger the double jeopardy clause of the U.S. Constitution. A majority of SCOTUS justices disagreed.

The judicial lineup, however, was somewhat atypical. Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote for the majority, which included Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, and Brett Kavanaugh. In dissent stood Justice Neil Gorsuch, whose opinion was partially joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Denezpi pleaded guilty to criminal assault in the Court of Indian Offenses (known as “CFR courts”) in 2017. He was released on time served. However, after a second investigation, Denezpi was indicted by a federal grand jury for the same incident, which had been a violent sexual assault. Denezpi was then prosecuted in federal court in Colorado, was found guilty, and was sentenced to 30 years in prison and ten years probation.

Denezpi appealed and lost at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit. At the nation’s highest court, Denezpi has now lost again.

Justice Barrett penned the majority opinion for the court. She called the case “a twist on the usual dual-sovereignty scenario.” According to Barrett and the six-member majority, Denezpi’s prosecutions did not amount to successive prosecutions by different sovereigns for the same offense. Rather, she said, he was separately prosecuted by the same sovereign for different offenses.

Barrett began her 13-page opinion with a bit of history of the CFR courts along with an explanation of the basics of CFR court functioning.

These courts were begun in 1882 by the Department of the Interior. Later, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs directed that a “Court of Indian Offenses” be established for nearly every Indian tribe. The courts get their name from the legal basis for their establishment: the Code of Federal Regulations — or “CFR.”

Indian tribes that have developed their own court systems no longer use their CFR courts. However, five CFR courts remain, which serve 16 of the more than 500 federally-recognized tribes. CFR court judges (called magistrates) are appointed by the Department’s Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, and are confirmed by the governing body of the tribe that the court serves. Judges can be removed for cause by the same Department Assistant Secretary, or by the recommendation of the tribal governing body.

CFR courts have jurisdiction over two sets of crimes: 1) those specifically defined in federal regulations; and 2) those that are enacted by the tribe and approved by the Assistant Secretary.

The 200-member Ute Mountain Ute Tribe uses a CFR Court, but has adopted its own penal code which is enforceable in that court. Denezpi’s crime was committed on the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation.

In her opinion, Barrett emphasized the sovereignty of the Indian tribes, as has been recognized in past SCOTUS opinions.

“[B]efore Europeans arrived on this continent, tribes ‘were self-governing sovereign political communities’ with ‘the inherent power to prescribe laws for their members and to punish infractions of those laws,'” she quoted from a 1978 case. Barrett explained that when a tribe enacts its penal code, it does not do so as “an arm of the Federal Government.” Rather, the tribe is a separate sovereign altogether.

Barrett elaborated and explained that when Denezpi barricaded the door, threatened a woman known as V.Y., and forced her to have sex with him, he violated both federal criminal law and tribal law. The Ute Mountain Ute Code prohibited assault and battery and the U.S. Code prohibited aggravated sexual abuse in Indian country.

Denezpi argued that because prosecutors in CFR courts exercise “federal authority” in that they operate under the umbrella of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, his CFR court prosecution and his federal prosecution were conducted by the same sovereign in violation of the guarantee against double jeopardy. SCOTUS, however, found that regardless of whether the prosecutors might be considered agents of the same sovereign, Denezpi’s double jeopardy claim fails, because there is simply no double jeopardy problem with successive prosecutions by the same sovereign for separate offenses.

Protection against double jeopardy, reasoned the majority, is not about the identity of the prosecutor. Rather, it is about protection from multiple prosecutions for the same offense. According to this majority, two different offenses do not raise double jeopardy concerns.

Barrett wrote that to read Denezpi’s argument together with legal history would produce the “nonsensical result” of considering a person’s single act to constitute two separate offenses at the time of commission, but then a single act at the time of prosecution.

Barrett also dispensed with Denezpi’s argument that allowing successive prosecutions undermines tribal sovereignty in a general sense. Barrett wrote: “the Tribe’s sovereign interest is furthered when its assault and battery ordinance—duly enacted by its governing body as an expression of the Tribe’s condemnation of that crime—is enforced, regardless of who enforces it.”

Gorsuch, the only justice hailing from the Western United States, took issue with the majority’s analysis in a 14-page dissent. Gorsuch summed up the facts by bluntly writing: “Same defendant, same crime, same prosecuting authority.” According to Gorsuch, Barrett and the other five justices in the majority went wrong right from the start in considering the CFR courts separate from the federal government. He called the CFR court “a creature of the Department of the Interior,” and explained, “Unlike a tribal court operated by a Native American Tribe pursuant to its inherent sovereign authority, the Court of Indian Offenses is ‘part of the Federal Government.'”

For a little more context, Gorsuch said that in 1883, CFR courts were opened by administrative decree to force Indian tribes to stop their “savage and barbarous practices,” and perceived lawlessness. Gorsuch continued, explaining that at the time, the federal government “outlawed everything from ‘old heathenish dances’ and ‘medicine men’ and their ‘conjurers’ arts’ to certain Indian mourning practices.”

Gorsuch’s take on the more current relationship between the federal government and the Indian tribes was primarily that it was complex. He explained that, on the one hand, “tribal members often regarded [CFR] courts as ‘foreign’ and ‘hated’ institutions,” even as the federal government has softened its attitude toward traditional tribal customs.

Gorsuch’s telling of Denezpi’s successive prosecutions is also different from that of the majority. Gorsuch relays the story of federal prosecutors who regretted their “hasty” prosecution under tribal law (which had merely resulted in a 6-month sentence rather than one spanning multiple decades). Gorsuch characterized the resulting sentence as the unfair result delivered by an authority that essentially got two bites at the same apple.

“Federal agency officials played every meaningful role in his case: legislator, prosecutor, judge, and jailor,” Gorsuch wrote.

In the portion of the dissent not joined by Sotomayor and Kagan, Gorsuch had harsh words for the CFR courts generally.

“By anyone’s account, the Court of Indian Offenses is a curious regime,” he began, pointing out that it was not authorized by any Act of Congress. Rather, Gorsuch said, “from the beginning, federal officials recognized that these ‘so-called courts’ rested on a ‘shaky legal foundation.'” And it’s not only the foundation that Gorsuch finds problematic.

“[O]ne might wonder,” the justice muses, “how an executive agency can claim the exclusive power to define, prosecute, and judge crimes—three distinct functions the Constitution normally reserves for three separate branches.” Gorsuch warned that the majority’s take on dual sovereignty as it relates to CFR courts could produce seriously problematic results.

“Taken to its extreme, it might allow prosecutors to coordinate and treat an initial trial in one jurisdiction as a dress rehearsal for a second trial in another,” he wrote.

The trio of dissenters ended with a reprimand for their fellow justices and their contribution to injustices long suffered by Native Americans. Nestled among Gorsuch’s words was an on-brand snipe at federal agencies:

It is hard to believe this Court would long tolerate a similar state of affairs in any other context— allowing federal bureaucrats to define an offense; prosecute, judge, and punish an individual for it; and then transfer the case to the resident U.S. Attorney for a second trial for the same offense under federal statutory law. Still, for over a century that regime has persisted in this country for Native Americans, and today the Court extends its seal of approval to at least one aspect of it. Worse, the Court does so in the name of vindicating tribal sovereign authority. The irony will not be lost on those whose rights are diminished by today’s decision.

[image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]