The Supreme Court of the United States ruled Monday in Ramos v. Louisiana. The case asked whether, in a state criminal trial, a jury verdict must be unanimous to convict a defendant of a serious offense. While the case itself centered around Sixth Amendment guarantees, the decision was far more about the Court’s future than it was about criminal justice.

The Backstory

Two states, Louisiana and Oregon, allow 10-to-2 verdicts to support a conviction.

Evangelisto Ramos was convicted of the stabbing death of Trinece Fedison, whose body was found in a trash can in New Orleans; Ramos was convicted by a 10-to-2 jury verdict, and was sentenced to life without parole. SCOTUS ruled in favor of Ramos, holding that conviction by a non-unanimous jury does, in fact, violate a person’s constitutional rights.

The Majority Decision

Right out of the gate, Justice Neil Gorsuch called out Louisiana’s non-unanimous jury law for what it was: racist in origin. Gorsuch wrote that while “it’s hard to say why these laws persist, their origins are clear.” He then gave some history of these rules, established as a means to establish white supremacy and to exclude African Americans from juries without explicitly saying so. “With a careful eye on racial demographics,” Gorsuch explained, “the [Louisiana lawmakers] sculpted a ‘facially race-neutral’ rule permitting 10-to-2 verdicts in order ‘to ensure that African-American juror service would be meaningless.’”

Gorsuch also reasoned that the Sixth Amendment’s plain-language guarantees a right to trial by impartial jury logically implies that no state law can simply abridge that right by creating a statute.

Ramos attorney Ben Cohen, Of Counsel at the Promise of Justice Initiative, said in a statement obtained by Law&Crime that he was pleased the Supreme Court “held, once and for all, that the promise of the Sixth Amendment fully applies in Louisiana, rejecting any concept of second-class justice.”

“Attorneys for the State of Louisiana claimed that a ruling for Mr. Ramos would result in 32,000 new trials. Justice Gorsuch responded to this claim at oral argument: ‘You say we should worry about the 32,000 people imprisoned. One might wonder whether we should worry about their interests under the Sixth Amendment,’” Cohen said. “Today, the United States Supreme Court has rejected these arguments and made clear that it is better to have to retry defendants convicted by a non-unanimous verdict than to enshrine in perpetuity a law born out of racism. ”

A Tough Precedent to Follow

The majority held that the Sixth Amendment’s “otherwise simple story took a strange turn in 1972,” when the Supreme Court ruled in Apodaca v. Oregon that the Sixth Amendment actually doesn’t guarantee a criminal defendant a unanimous jury if we’re talking about state (as opposed to federal) trials. Gorsuch lambasted what he referred to as “dual-track” incorporation—the concept that the Sixth Amendment means one thing when invoked against the federal government, but something entirely different in the context of state law.

The Apodaca decision was itself something of a disaster; a plurality decision in which a splintered bench couldn’t quite agree on much led to a precedent that was messy to follow. Gorsuch called Apodaca “an admittedly mistaken decision, on a constitutional issue, an outlier on the day it was decided, one that’s become lonelier with time.”

The Real Question: How Important Is Stare Decisis?

Ultimately, the majority ruled to do what was “right” within the context of the Sixth Amendment and its history, as opposed to sticking with the Apodaca rule because of stare decisis. Speaking of past precedent, Gorsuch pretty much shredded the dissenters’ take on blind deference. First, Gorsuch accused the dissenters of being “oddly coy” in even defining Apodaca’s precedent. He did not stop there:

“Even if we accepted the premise that Apodaca established a precedent, no one on the Court today is prepared to say it was rightly decided, and stare decisis isn’t supposed to be the art of methodically ignoring what everyone knows to be true.”

Arguing that the majority couldn’t possibly affirm Ramos’s obviously unconstitutional conviction, Gorsuch had harsh words for his brethren. “In the final accounting,” he wrote, “the dissent’s stare decisis arguments round to zero.”

“Every judge must learn to live with the fact he or she will make some mistakes; it comes with the territory,” Gorsuch concluded. “But it is something else entirely to perpetuate something we all know to be wrong only because we fear the consequences of being right.”

Three Very Different Concurrences

Justice Sonia Sotomayor concurred, underscoring the importance of the racist origins of Louisiana’s non-unanimous jury law, emphasizing that “overruling precedent here is not only warranted, but compelled.”

By contrast, Justice Brett Kavanaugh used his concurrence to keep one foot in both camps. He agreed with the majority that it was time to overrule Apodaca, but simultaneously clarified that he’s still a pretty big fan of stare decisis in general. To put some serious muscle behind it all, Kavanaugh even quoted Federalist 37, one of James Madison’s essays.

Explaining why the Ramos case presents the rare opportunity to appropriately overturn precedent, Kavanaugh characterized the situation as follows:

“No Member of the Court contends that the result in Apodaca is correct. But the Members of the Court vehemently disagree about whether to overrule Apodaca.”

One can almost feel the relevance Kavanaugh’s reasoning will have in the future, when the issue isn’t unanimous juries, but reproductive freedom or religious liberty. Kavanaugh sets up the contrast now, by pointing out that the unanimous jury rule is one on which all the justices agree.

Ever the contrarian Justice Clarence Thomas concurred in the judgment, but wrote that he’d have decided the case on entirely different “Privileges and Immunities” grounds, as opposed to due process ones.

A Foreshadowing Dissent

Justice Samuel Alito offered a dissent that was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and joined, in part, by Justice Elena Kagan.

Alito gave the usual fire and brimstone warning of a world that would end without stare decisis to save it:

“The doctrine of stare decisis gets rough treatment in today’s decision. Lowering the bar for overruling our precedents, a badly fractured majority casts aside an important and long-established decision with little regard for the enormous reliance the decision has engendered. If the majority’s approach is not just a way to dispose of this one case, the decision marks an important turn.”

Alito wasn’t having the majority’s accusation that Louisiana and Oregon were perpetuating Jim Crow. Accusing the majority of adding “insult to injury,” by “tar[ring] Louisiana and Oregon with the charge of racism for permitting nonunanimous verdicts,” Alito reasoned:

“Some years ago the British Parliament enacted a law allowing non-unanimous verdicts. Was Parliament under the sway of the Klan? The Constitution of Puerto Rico permits non-unanimous verdicts. Were the framers of that Constitution racists? Non-unanimous verdicts were once advocated by the American Law Institute and the American Bar Association. Was their aim to promote white supremacy? And how about the prominent scholars who have taken the same position? Racists all? Of course not.”

According to Alito, the majority’s decision in Ramos isn’t just intellectually wrong but wildly impractical, too. Warning that Louisiana and Oregon will now face a “tsunami of litigation on the jury unanimity issue,” Alito chastised the majority for throwing out a precedent upon which “thousands” of trials in Louisiana have been based.

Alito ended the dissent by throwing down the ultimate gauntlet:

“By striking down a precedent upon which there has been massive and entirely reasonable reliance, the majority sets an important precedent about stare decisis. I assume that those in the majority will apply the same standard in future cases.”

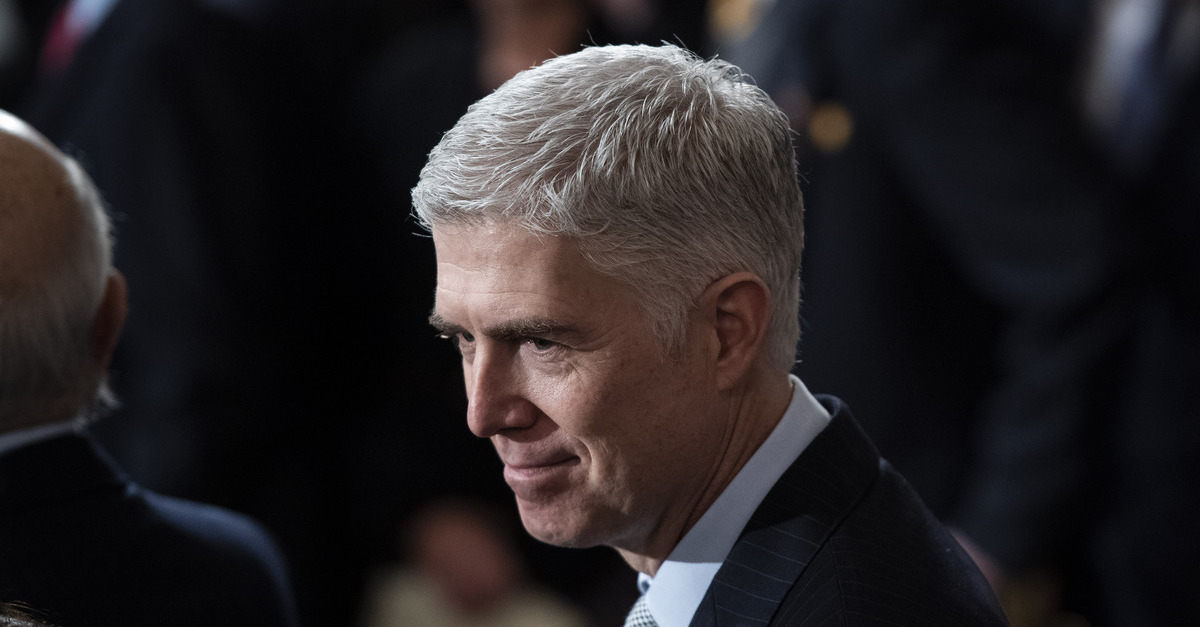

[image via Jabin Botsford/Getty Images]