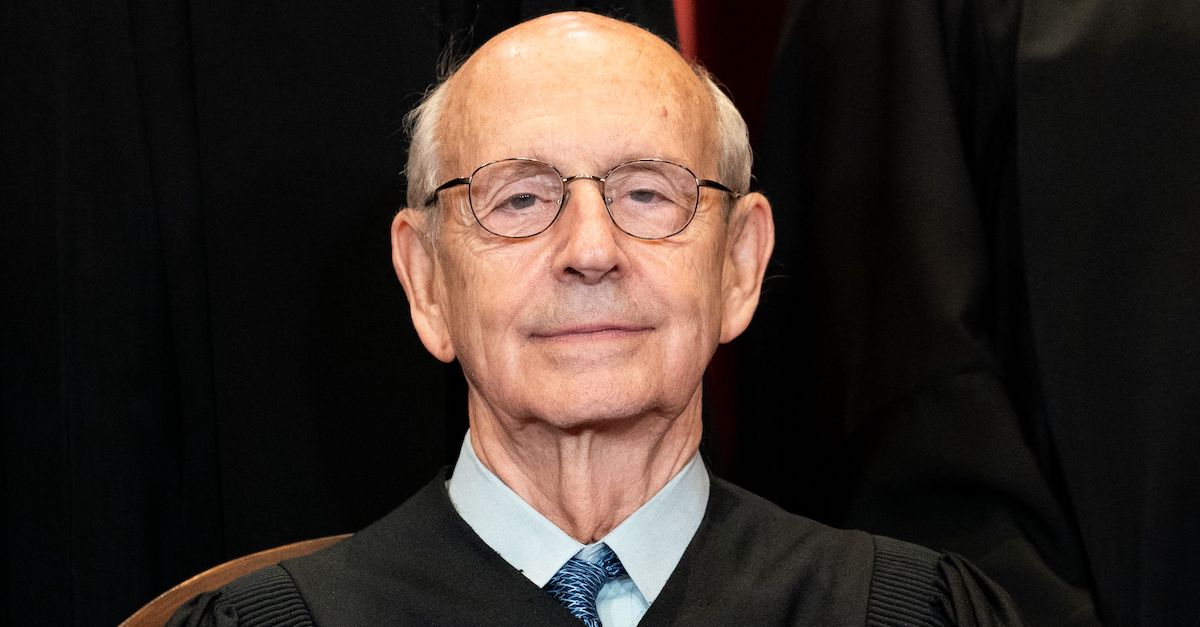

Associate Justice Stephen Breyer sits during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021.

The Supreme Court of the United States on Monday declined to review a death penalty case involving the oldest prisoner on death row in Texas. Writing in the mold of a traditional legal liberal, Justice Stephen Breyer expressed his belief that the death penalty itself is likely unconstitutional.

Carl Wayne Buntion was convicted of murder in 1991 for the killing of Houston Police Department officer James Irby during a traffic stop in 1990. After being sentenced to death, Buntion’s sentencing was found to be deficient and unconstitutional by a Texas appeals court. During the original sentencing phase of his trial, jurors did not hear evidence about the convicted man’s abusive childhood and that was deemed an error that could have impacted the eventual sentence.

In 2012, the sentencing phase was re-tried and jurors were given insight into the convicted killer’s upbringing. That additional information didn’t change a thing, however, and Buntion was re-sentenced to death in March of that year. More appeals followed.

In 2016, Buntion appealed on 27 different points of alleged error to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. The court unanimously denied the requested relief. In 2018, that verdict was appealed to the nation’s high court but the nine justices declined to take up the case.

After failing to have his case reviewed, Buntion timely filed more appeals in state and federal courts, raising habeas corpus issues. Those cases were summarily denied and Buntion appealed again, this time within the confines of habeas corpus law–seeking a certificate of appealability–which allows a petitioner to appeal a denial of the writ.

But each time around, Buntion failed. He finally appealed the denial from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit up to the Supreme Court and failed there as well. Overall, Buntion’s case is a textbook example of the slow-winding appeals process as it relates to capital punishment cases. And, in Breyer’s opinion, something of a tragic one.

“[Buntion] has now been on death row under threat of execution for 30 years,” the justice noted, casting a decidedly somber tone. “He tells us that he has spent the last 20 of those years in solitary confinement, isolated in his cell for 23 hours a day. He further tells us that, at age 77, he is now the oldest prisoner on Texas’ death row. Texas does not dispute these facts. Buntion now asks the Court to consider whether execution after such an extended delay is cruel and unusual in violation of the Eighth Amendment.”

Breyer’s brief one-and-a-half-page “statement” that respects the high court’s denial operates under no illusions, though, and is plainly an expression of the jurist’s principles.

“I recognize the procedural obstacles that make it difficult for the Court to grant certiorari in Buntion’s case,” the justice’s statement reads. “I write, however, to underscore how this case illustrates the problems with the death penalty.”

Breyer goes on to catalogue a series of cases in which he has opined in dissent about such problems before bringing the current case into the realm of actual precedent by citing to the court’s majority opinions on the always-contentious matter of life and death.

From the statement, at length:

I continue to believe that excessive delay both “undermines the death penalty’s penological rationale” and is “in and of itself . . . especially cruel because it ‘subjects death row inmates to decades of especially severe, dehumanizing conditions of confinement.’” The Court has previously recognized that the uncertainty of waiting in prison under the threat of execution, even for a span of just four weeks, is “one of the most horrible feelings to which [a person] can be subjected.” In re Medley, 134 U. S. 160, 172 (1890). On top of that, solitary confinement bears “‘a further terror and peculiar mark of infamy.’” Id., at 170; see also Davis v. Ayala, 576 U. S. 257, 289 (2015) (Kennedy, J., concurring) (“Years on end of near total isolation exact a terrible price”).

Here, Breyer would have found that Buntion’s case at least bears striking similarities to what other justices have warned about what to look for in death penalty cases in the past–but he admits that such an argument before the present court would be an uphill slog.

“Buntion has now been subjected to those conditions for decades,” the statement concludes. “His lengthy confinement, and the confinement of others like him, calls into question the constitutionality of the death penalty and reinforces the need for this Court, or other courts, to consider that question in an appropriate case.”

[image via ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images]