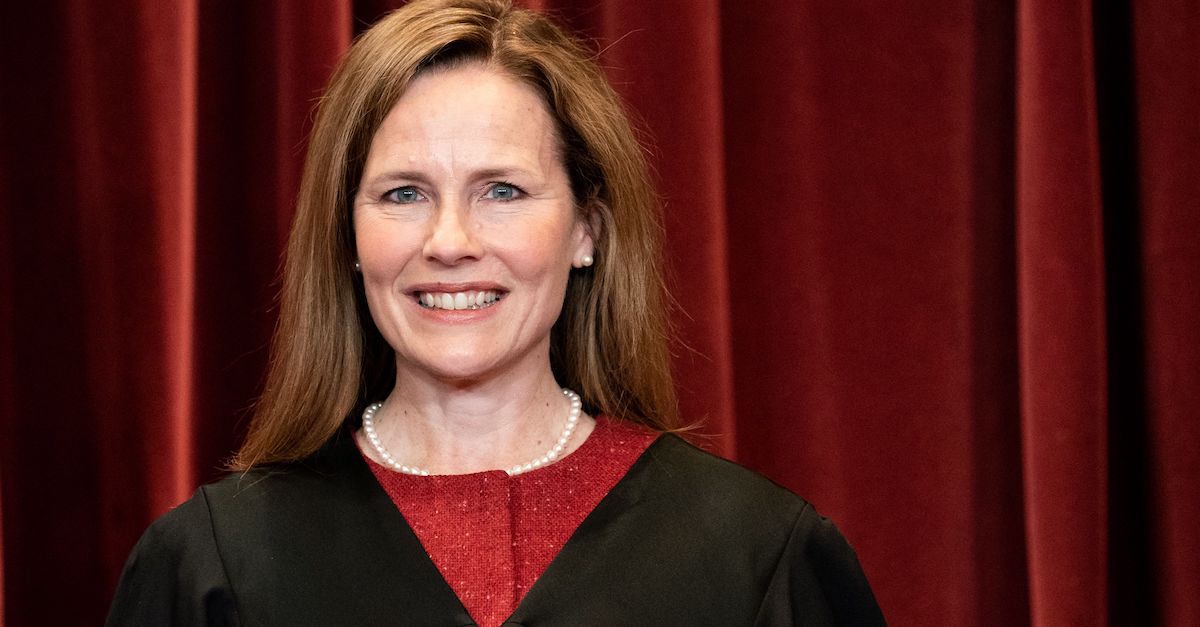

Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett stands during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021.

The Supreme Court of the United States on Monday overturned an appellate court ruling that advanced a class action lawsuit against Goldman Sachs over the 2008 financial crisis, giving the bank another opportunity to argue that generically self-serving statements did not amount to securities fraud.

Splitting with three of her conservative peers, Justice Amy Coney Barrett was the lead author of the majority opinion that could make Goldman’s victory short-lived. The bank will still bear the burden of showing that puffery about their corporate practices did not meaningfully move the market.

“We are pleased the Supreme Court has vacated the grant of class certification and we will continue to vigorously defend ourselves as the case returns to the lower courts,” Goldman Sachs spokesperson Maeve DuVally told Law&Crime in an email.

Counsel for the proposed class of shareholders did not immediately respond to an email requesting comment.

After this story was published, investors rights groups also praised the ruling–and moderately criticized the famed investment bank for their interpretation of the court’s decision in the case.

“We applaud the U.S. Supreme Court for upholding investor rights in its decision in the Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, et al. case, rejecting Goldman’s cynical attempt to evade accountability by shifting the burden of proof onto investors,” the Consumer Federation of America, the American Association for Justice and Public Justice said in a joint statement provided to Law&Crime. “By upholding existing law, with the burden of persuasion firmly on the defendants, the Court’s decision upholds the rights of investors to seek accountability in the future.”

“The consequences of giving Goldman (and other companies) an explicit green light for misconduct would have been devastating for investor confidence in the markets,” that statement continued. “Should Goldman choose to characterize this a ‘win,’ it will say a great deal about how the company sees foot-dragging and justice deferred for investors as good things. While the case was remanded back to the Second Circuit, nothing in the decision suggests that the Second Circuit decision to certify the class was made in error. Indeed, we agree with Justice Sotomayor that it was not. We are hopeful that the case will finally be able to proceed once the Second Circuit reviews all of the evidence pursuant to the Court’s decision, giving Goldman’s investors long overdue justice.”

A relatively brief and tidy opinion, the decision is pockmarked by a series of concurrences and dissents that carve up the ruling along ideological lines and their real world implications.

Stylized as Goldman Sachs Group v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, the original lawsuit here was brought by various teachers, other state employees, plumbers, pension funds and individual shareholders who lost money during the Great Recession after the Manhattan-based investment bank’s stock price tanked.

Far from run-of-the-mill disgruntled investors, however, the shareholders claimed that Goldman Sachs made numerous, glowing, and misleading public statements about the bank’s business practices. In hindsight, those statements artificially inflated the bank’s stock price at the time the investments at issue were made, the plaintiffs claimed.

Various lower courts advanced the shareholders’ lawsuit.

“At times, Goldman allegedly represented to its investors that it was aligned with them when it was in fact short selling against their positions,” the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit explained.

The facts of the case are not new or controversial.

Goldman Sachs often made deals that directly undercut their own clients’ position by betting that many of their clients would fail. During the 2008 financial crisis—and the directly resulting crisis that was the subprime mortgage scandal—that’s exactly what happened, the lawsuit charges.

“Plaintiffs allege here that between 2006 and 2010, Goldman maintained an inflated stock price by making repeated misrepresentations about its conflict-of-interest policies and business practices,” Barrett notes. “The alleged misrepresentations are generic statements from Goldman’s SEC filings and annual reports.”

Playing both sides of the real estate market stood in stark contrast to statements such as the following highlighted in Monday’s opinion:

- “We have extensive procedures and controls that are designed to identify and address conflicts of interest.”

- “Our clients’ interests always come first.”

- “Integrity and honesty are at the heart of our business.”

“According to Plaintiffs, these statements were false or misleading—and caused Goldman’s stock to trade at artificially inflated levels—because Goldman had in fact engaged in several allegedly conflicted transactions without disclosing the conflicts,” the majority ruling continues. “Plaintiffs further allege that once the market learned the truth about Goldman’s conflicts from a Government enforcement action and subsequent news reports, the inflation in Goldman’s stock price dissipated, causing the price to drop and shareholders to suffer losses.”

Writing for a highly-fractured majority, Justice Barrett remained agnostic on the level of culpability the bank should be on the hook for due to the above statements and numerous others like them.

In fact, deciding that issue wasn’t really the court’s task. The major outstanding issue is whether the “generic nature” of those misleading statements should be considered and whether or not the appellate court took the nature of the statements into consideration when allowing the plaintiffs to certify their class action against the bank. A secondary question is a matter of who bears the burden of proving how important that information is for class certification purposes.

The nation’s high court issued a narrow ruling that cuts both ways: giving the bank a victory by remanding and telling the Second Circuit to consider “generic nature” evidence and putting the shareholders in a favorable position going forward by putting the burden on Goldman Sachs to prove that this evidence is actually enough to deny class certification.

“On the first question, the parties now agree, as do we, that the generic nature of a misrepresentation often is important evidence of price impact that courts should consider at class certification,” the opinion reads. “Because we conclude that the Second Circuit may not have properly considered the generic nature of Goldman’s alleged misrepresentations, we vacate and remand for the Court of Appeals to reassess the District Court’s price impact determination.”

On the second question, Barrett determined that Goldman Sachs bears the burden of showing whether or not the “generic nature” evidence can stop the aggrieved investors from suing collectively.

But, and quite notably, the most recently minted justice also said that this inquiry may not end up determining things any differently. Justice Barrett explains:

Although the defendant bears the burden of persuasion, the allocation of the burden is unlikely to make much difference on the ground. In most securities-fraud class actions, as in this one, the plaintiffs and defendants submit competing expert evidence on price impact. The district court’s task is simply to assess all the evidence of price impact—direct and indirect—and determine whether it is more likely than not that the alleged misrepresentations had a price impact. The defendant’s burden of persuasion will have bite only when the court finds the evidence in equipoise—a situation that should rarely arise.

A trio of conservative justices dissented in part and concurred in part–as did the court’s most left-leaning member.

Led by Justice Neil Gorsuch, Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas agreed with the decision to remand for further inquiry into the “generic nature” evidence but disagreed with the point of law expressed by the majority that defendants here bear the burden.

I join all but Part II–B of the Court’s opinion. There, the Court holds that the defendant, rather than the plaintiff, “bear[s] the burden of persuasion on price impact.” Ante, at 9. Respectfully, I disagree.

Goldman Sachs argued, and the dissent endorsed, a highly complicated method that would swap the burden out here.

But Barrett and the majority were not interested in any of that–arguing the dissent’s understanding would break precedent in an odd way.

“If, as they urge, the defendant could defeat [the longstanding] presumption by introducing any competent evidence of a lack of price impact—including, for example, the generic nature of the alleged misrepresentations—then the plaintiff would end up with the burden of directly proving price impact in almost every case,” the majority explained.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, for her part, wrote her own opinion staking out precisely the inverse of the gripe by the court’s right flank.

Sotomayor agrees with all the points of law opined upon in the case but disagrees that the case should be remanded–decidedly coming down in favor of the pension funds.

“I believe the Second Circuit ‘properly considered the generic nature of Goldman’s alleged misrepresentations,'” she wrote.

Defending the Second Circuit’s ruling, Sotomayor is an alum of that New York City-based federal appeals court.

[image via ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images]

Editor’s note: this article has been amended post-publication to include the newest version of an additional statement.