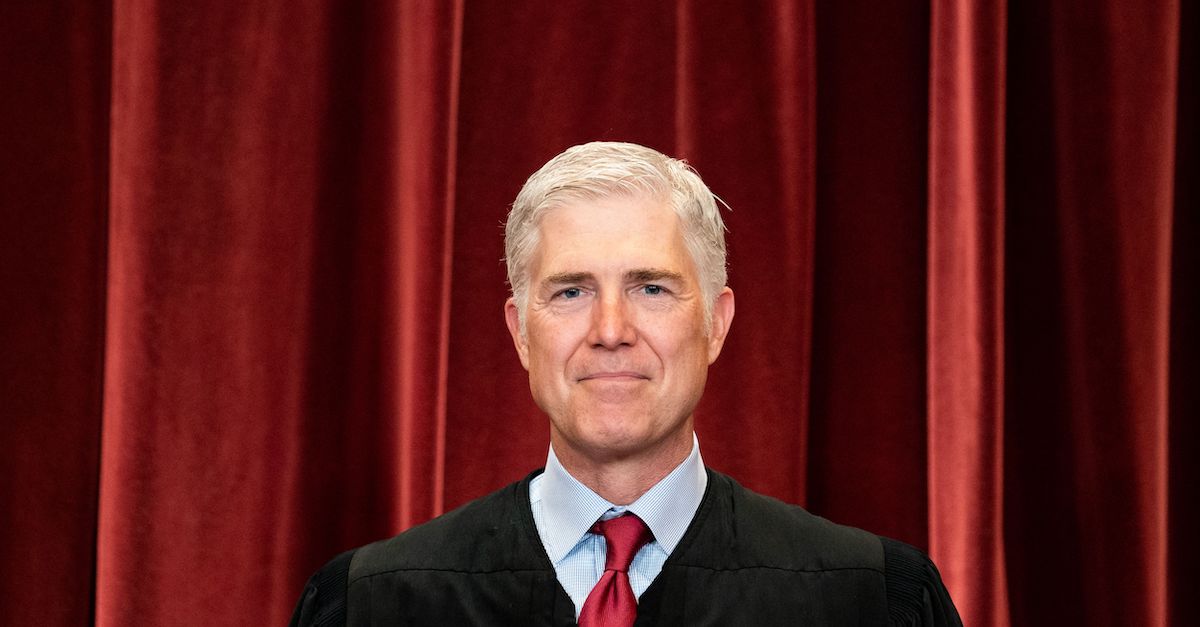

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch.

The justices of the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments Tuesday in the cases of two doctors found guilty of operating so-called “pill-mills.” As the justices conducted questions to tease out the right way to interpret the criminal statute at issue, conversation often returned to the role of mens rea — or mental state. Specifically, the justices wanted to know how to separate a doctor who has a sincere belief that he’s doing the right thing by prescribing pills but who is violating the standard of care (either by negligence or more) from a doctor who is criminally overprescribing medication. The latter is the realm of prosecution efforts; the former, of course, is the realm of a potential civil actions.

The consolidated cases, Ruan v. United States and Kahn v. United States, together ask the justices to settle a circuit court dispute over a physician’s right to assert good faith as a defense against criminal charges under the Controlled Substances Act.

That Act makes it illegal for “any person knowingly or intentionally . . . to manufacture, distribute, or dispense” certain prohibited controlled substances without being explicitly “authorized” by the law. The law naturally and logically authorizes doctors to prescribe certain drugs in accordance with myriad rules and regulations. But, as a petition for a writ of certiorari in Ruan points out, “[a] physician otherwise authorized to prescribe controlled substances may be convicted of unlawful distribution under 21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1) if his prescriptions ‘fall outside the usual course of professional practice‘” — the latter language having been handed down by the Supreme Court in U.S. v. Moore (1975).

In all federal circuits except the Eleventh Circuit, physicians are permitted to raise their own good faith beliefs as a defense if they’re prosecuted. The Second, Fourth, and Sixth Circuits focus on a physician’s “reasonable belief” that prescriptions were medically sound and appropriate. “Reasonable belief” is generally a broad, overarching standard that’s objective, not subjective. By contrast, the First, Seventh, and Ninth Circuits look only at the physicians’ subjective beliefs. The Eleventh Circuit does not recognize either version of the defense when a doctor has been shown to have prescribed controlled substances in contravention of generally accepted medical standards.

Or, as the Ruan brief noted, “the circuits are deeply divided” — to put it mildly.

The Ruan case involves Dr. Xiulu Ruan, a physician who ran an Alabama a medical clinic and pharmacy. Per the brief, Dr. Ruan was indicted for unlawful distribution of controlled substances under the Controlled Substances Act, racketeering conspiracy, health care fraud conspiracy, wire fraud conspiracy, and related charges. Prosecutors alleged that Ruan improperly issued over 300,000 prescriptions for controlled substances over a four-year period, making him one of the nation’s top prescribers of the opioid fentanyl. Furthermore, Ruan was said to have taken a financial stake in the drug manufacturers. In the companion case, Dr. Shakeel Kahn is alleged to have traded drugs for cash, sometimes without any corresponding examination or proper documentation.

At Ruan’s trial, the government acknowledged that some prescriptions were given to the clinic’s “legitimate patients” but argued that others “fell outside of professional norms.” Prosecutors provided evidence that the physician prescribed too many opioids, failed to recognize patients’ red flags, failed to make appropriate referrals, and failed to keep appropriate records. The defendant doctor put on a robust case of his own, offering expert testimony that his treatments had been recommended in good faith. Similarly, Kahn was convicted despite his argument that he sincerely believed he was appropriately providing medication to his patients.

At issue in both cases are the jury instructions provided by the court which mentioned, but may have failed to appropriately emphasize, the role of the physician’s good faith as evidence negating a guilty verdict.

Attorney Lawrence Robbins argued on behalf of Ruan and was the first to face the justices’ analogy-based questions. Chief Justice John Roberts offered a hypothetical in which a driver was pulled over for speeding when that driver honestly believed he was traveling at a legal speed, then a corresponding one in which the driver knew he was driving in excess of the lawful limit, but believed the law should have authorized his speed. “You’d still get a ticket, right?” asked Roberts — and Robbins agreed.

Justice Samuel Alito turned the conversation to a strict grammar-based interpretation of the statute in question, commenting that his “old English teacher” would disagree with Robbins’ interpretation of the statute.

Disagreeing with Alito’s take on the statute, Robbins offered a statement on “what the world would look like” under Alito’s interpretation of the law.

“In that world, a doctor’s only defense is that he didn’t know he was prescribing a controlled substance,” said Robbins. “I suggest that that would mean that the only doctors who could possibly be acquitted have prescribed the medicine in a coma.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch stepped in with a distinctly helpful line of questions for Robbins.

“Let’s assume Justice Alito’s grammar teacher was right,” Gorsuch began. “I know you don’t want to, but let’s just assume that.”

Gorsuch then lead Robbins through a possible interpretation of the statute. First, Gorsuch offered that the exceptions listed in the statute require a mens rea element to distinguish lawful from unlawful conduct; next, he suggested that the government need not negate all the statute’s exceptions but rather would have the burden of proving all statutory elements after a defendant bore the burden of production and invoked one particular exception.

“I agree with all that,” responded Robbins, who then began to elaborate.

“Be careful,” Gorsuch warned, interrupting Robbins.

“You were just helped, counselor,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed out to Robbins.

When Khan’s attorney, Beau Brindley, took the podium, he focused on the statue’s underlying purpose. Arguing that the law was meant to curtain drug trafficking, Brindley maintained that Robert’s speeding analogy does not accurately capture the dispute before the Court.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh raised the role of jurors in prosecutions under the statute. If a doctor were to come forward with an “outlandish theory about what he or she subjectively believed” to be the standard of medical care, the jury will almost certainly disbelieve the defense.

Alito, however, was not satisfied with the scenario Kavanaugh raised.

“What if the jury doesn’t disbelieve it?” Alito asked Brindley. “What if a doctor really sincerely thinks that a process that is objectively outlandish is the legitimate practice of medicine? In your view, that doctor must be acquitted, right?”

Brindley answered that indeed, such a doctor should be acquitted, as his actions would not sufficiently constitute drug trafficking within the intent of the statute.

Alito hammered the point again.

“But what if it is that the doctor legitimately believes that legitimate medical practice encompasses giving people that are dependent on drugs the drugs they need to satisfy that dependency . . . that doctor has to be acquitted in your view?” he asked Brindley.

The attorney agreed, but qualified that such a situation “is not very likely to occur.”

“No, it’s not likely,” Alito quipped, “but that’s what your interpretations means.”

Once again, Justice Gorsuch jumped in with an assist.

“Why would that be the case, counsel?” Gorsuch asked. “If the evidence is that legitimate medical practice doesn’t include the behavior of your client in this case, and the jury could infer that your client knew that he would be guilty even if he had some idiosyncratic views about what medical practice should look like.”

Justice Amy Coney Barrett next offered what she called “a closer analog” than the speed-limit example presented by the Chief Justice. Barrett’s example was a driver who knew they were exceeding the posted speed limit but thought they were entitled to a legal exception based on the fact that they were transporting a child to the emergency room.

Brindley agreed, saying that the only thing that makes a doctor’s prescription-writing improper is the absence of a legitimate medical purpose. “If he’s sincerely wrong about that,” argued Brindley, “he lacks a culpable state of mind and should’t be convicted” in a criminal court.

Deputy Solicitor General Department of Justice Eric Feigin argued on behalf of the Department of Justice and faced multiple questions from the bench about how the statute should be drafted.

Justice Gorsuch returned the discussion again to the concept of mens rea.

“I understand the government will never bring a close case,” Gorsuch said sarcastically as he asked Feigin to hypothetically assume a close case where a jury does not believe a doctor has acted with a legitimate medical purpose.

“That person stands unable to shield himself behind any mens rea requirement and is subject to essentially a regulatory crime, subject to 20 years or maybe life in person,” said Gorsuch.

Law&Crime spoke with law professor, nurse, and bioethicist Kelly Dineen, who was a co-author on the amicus brief supporting the petitioners in the case. Dineen argued that “the 10th and 11th Circuits have essentially eliminated all aspects of the culpable mental state” in their approach, which she said was problematic for a number of reasons. Among them was that it gives the federal government “an outsized role in the regulation of medical practice.” Dineen also said she was “cautiously optimistic that the Court will issue an opinion favorable to the petitioners” after hearing oral arguments Tuesday. Though she was “unsure as to the route the Court will take,” she said she believes the case will be remanded to the circuit courts.

[image via Erin Schaff/POOL/AFP via Getty Images]