Sen. Josh Hawley, a constitutional lawyer, Republican senator from Missouri and member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, said Tuesday that Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett met his criteria for the position. Hawley said that he “wanted to see evidence that the nominee understood that Roe was wrongly decided, that Roe was an act of judicial imperialism.” If Hawley is approving of Judge Barrett for meeting his criteria, it follows that he has seen some “evidence” that Barrett believes Roe v. Wade was wrongly decided.

It’s unclear exactly what evidence Hawley is referring to here, but Hawley made the remarks on Tuesday, which is the same day that Judge Barrett’s Senate questionnaire was released.

The most likely pieces of evidence in the questionnaire pertain to things Judge Barrett has actually said and written about Roe v. Wade and stare decisis—namely, the judicial policy of adhering to precedent. In this context, this is the Supreme Court adhering to its own precedent. It should be said outright that thinking Roe was wrongly decided and thinking that, because of that, precedent should be overturned are two different things. The latter is the more important of the two.

On Jan. 18, 2013, Barrett presented a lecture at the University of Notre Dame titled, Roe at 40: The Supreme Court, Abortion and the Culture War that Followed. According to the student newspaper account of what was said, Barrett raised a question that one often hears in discussions about whether Roe v. Wade was wrongly decided.

“It brings up an issue of judicial review: Does the Court have the capacity to decide that women have the right to obtain an abortion or should it be a matter for state legislatures? Would it be better to have this battle in the state legislatures and Congress rather than the Supreme Court?” she asked.

“Roe was a dramatic shift,” Barrett said. “The framework of Roe essentially permitted abortion on demand, and Roe recognizes no state interest in the life of a fetus.”

Barrett, perhaps not imagining that she would one day be in line for a Supreme Court seat, noted that confirmation hearings have turned into “battles” precisely because Republicans want to appoint justices who may overturn Roe and Democrats want to preserve a woman’s right to obtain an abortion. Then she turned to the Supreme Court case Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which in reaffirming Roe, held that “matters,” such as abortion, “involving the most intimate and personal choices a person may make in a lifetime, choices central to personal dignity and autonomy, are central to the liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.” Planned Parenthood v. Casey also prohibited abortion regulations that place an “undue burden” on women.

Barrett, who was still a law professor at Notre Dame in 2013, noted that Casey “is a case that alters Roe but preserves the core of Roe.”

“As of the Casey ruling, before viability the state policy may not pose a substantial obstacle to a woman’s obtaining an abortion, but the state can regulate in the interest of the life of the fetus. Casey also stated that after viability the state can regulate with an exception for health of the mother,” Barrett said. Barrett predicted that it was, as of 2013, “very unlikely” that the Supreme Court would “overturn Roe, or Roe as curbed by Casey.”

“The fundamental element, that the woman has a right to choose abortion, will probably stand,” Barrett continued. “The controversy right now is about funding. It’s a question of whether abortions will be publicly or privately funded.”

But now we are moving into territory where Barrett will presumably join and add to an already strong conservative majority on the Supreme Court. It’s impossible to know, but the former Federalist Society member’s words “very unlikely” and “will probably stand”—clearly not absolute terms—may have been different words if the current-and-future-iteration of the court was in place when she uttered them in 2013. In 2013, Anthony Kennedy, the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Barrett’s mentor Antonin Scalia were on the court.

In 2020, the court will all but certainly be Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Barrett, Brett Kavanaugh, Neil Gorsuch, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor. Would-be challengers of abortion laws will be emboldened by this, and they may thinking beyond questions like whether or not abortions should be publicly funded.

This brings us to concepts of stare decisis and super-stare decisis or “super-precedent.” If stare decisis is a judge-made policy weighing against the overturning of past precedent, super-stare decisis speaks of a precedent with super-immunity from being overturned.

Barrett’s own writings, again from 2013, provide insight into her views on this, and they suggest that she doesn’t view Roe as super-precedent that is virtually immune from reconsideration. This law review piece was noted in the Senate questionnaire.

Barrett began “Precedent and Jurisprudential Disagreement” by writing that “stare decisis is a soft rule” that the Supreme Court “describes […] as one of policy rather than as an ‘inexorable command”—which is an understanding shared by Trump-appointed Justices Kavanaugh and Gorsuch.

Barrett notes that her law review article was addressing the “force that stare decisis should have in one particular context: when a Supreme Court justice confronts constitutional precedent with which she disagrees.” She framed the range of the debate as follows:

Scholars have a range of views about how the Court should behave when deciding whether to overrule constitutional precedent. Those who favor weak stare decisis tend to do so because of their methodological commitments. Thus, some living constitutionalists have argued for freedom to overrule lest precedent hinder progress, and some originalists have argued for freedom to overrule lest doctrine trump the document.

The originalist school of thought Barrett described there would argue that judge-made doctrine should not supersede original meaning of the Constitution.

Barrett said she was setting out to write an account of “weak stare decisis” that is “not grounded in the claim that any particular methodological commitment demands that approach.” She wrote that a “more relaxed form of constitutional stare decisis” is “both inevitable and probably desirable, at least in those cases in which methodologies clash.” The focus here, again, is on the individual justice confronting a precedent they disagree with.

Barrett defined “superprecedents” as “cases that no justice would overrule, even if she disagrees with the interpretive premises from which the precedent proceeds.” Barrett favorably cited constitutional scholar Michael Gerhardt’s explanation of the subject.

Moments later, Barrett said her view is that “superprecedents’ do not illustrate a ‘super strong’ effect of stare decisis at all,” and cited Casey as a prime example [emhpasis and clarification ours]:

Stare decisis is a self-imposed constraint upon the Court’s ability to overrule precedent. The force of so-called superprecedents, however, does not derive from any decision by the Court about the degree of deference they warrant. Indeed, Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey shows that the Court is quite incapable of transforming precedent into superprecedent by ipse dixit [editor’s note: that’s Latin for just because the court says so]. The force of these cases derives from the people, who have taken their validity off the Court’s agenda. Litigants do not challenge them [superprecedents]. If they did, no inferior federal court or state court would take them seriously, at least in the absence of any indicia that the broad consensus supporting a precedent was crumbling.

At the end of the ipse dixit line, Barrett added a footnote that appears to suggest that she doesn’t think of Roe is super-precedent because it remains highly controversial, again citing Gerhardt. But Barrett also cited Harvard Law Professor Richard H. Fallon’s observation on the subject [bold ours] that Roe has “acquired no immunity from serious judicial reconsideration”:

In an op-ed in The New York Times, Senator Specter characterized Roe v. Wade as a superprecedent. Arlen Specter, Op-Ed., Bringing the Hearings to Order, N.Y. TIMES, July 24, 2005. Scholars, however, do not put Roe on the superprecedent list because the public controversy about Roe has never abated. See, e.g., Fallon, supra note 51, at 1116 (“[A] decision as fiercely and enduringly contested as Roe v. Wade has acquired no immunity from serious judicial reconsideration, even if arguments for overruling it ought not succeed.”); Gerhardt, supra note 129, at 1220 (asserting that Roe cannot be considered a superprecedent in part because calls for its demise by national political leaders have never retreated).

Beyond this, the Senate questionnaire also unsurprisingly supported, in at least two instances, Judge Barrett’s conservative Catholic and pro-life bona fides.

Judge Barrett participated in Notre Dame’s University Faculty for Life Group from 2010-2016. The questionnaire noted that “participation” means “consistent repeated involvement in a given organization, membership, or regular attendance at events of meetings.”

Here’s what the ND UFL website says the group exists to do [emphases ours]:

ND UFL is organized to promote research, dialogue, and publication by faculty, administration, and staff who respect the sacred value of human life from its inception to natural death in the spirit embodied in Evangelium Vitae and Caritas in Veritate and are committed to the legal and societal recognition of the value of all human life. ND UFL is committed to providing an interdisciplinary forum for the discussion of the political, social, legal, medical, biological, psychological, ethical, and religious dimensions of life issues. It seeks to promote the prolife cause at Notre Dame through a variety of academic and other activities.

Evangelium Vitae (“human life, as a gift of God, is sacred and inviolable. For this reason procured abortion and euthanasia are absolutely unacceptable…”) and Caritas in Veritate (“Yet we must not underestimate the disturbing scenarios that threaten our future, or the powerful new instruments that the ‘culture of death’ has at its disposal. To the tragic and widespread scourge of abortion we may well have to add in the future — indeed it is already surreptitiously present — the systematic eugenic programming of births…”) are papal encyclicals by Pope St. John Paul II and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI respectively.

Then there’s the small detail that Barrett once received the St. Thomas More Award at a St. Thomas More Society dinner in Dallas, Texas in 2018 [emphasis added].

“The St. Thomas More Society of the Diocese of Dallas, Texas, is open to Catholic lawyers, judges, public servants and officials active in the legal profession, and all individuals who are interested in the relationship between the Catholic faith and the law,” the group notes. “The purpose of the Society is to encourage Catholic lawyers within the diocese of Dallas to live a Christian vocation by sanctifying their daily work.”

Then there is the report that Barrett once signed a letter in 2006 calling for an end to “abortion on demand” and defending the “right to life from fertilization to natural death.” The associated page next to the signatures called Roe, quoting Justice Byron White, an “exercise of raw judicial power,” which mirrors Sen. Hawley’s “judicial imperialism” line. The pro-life ad also called Roe “barbaric.”

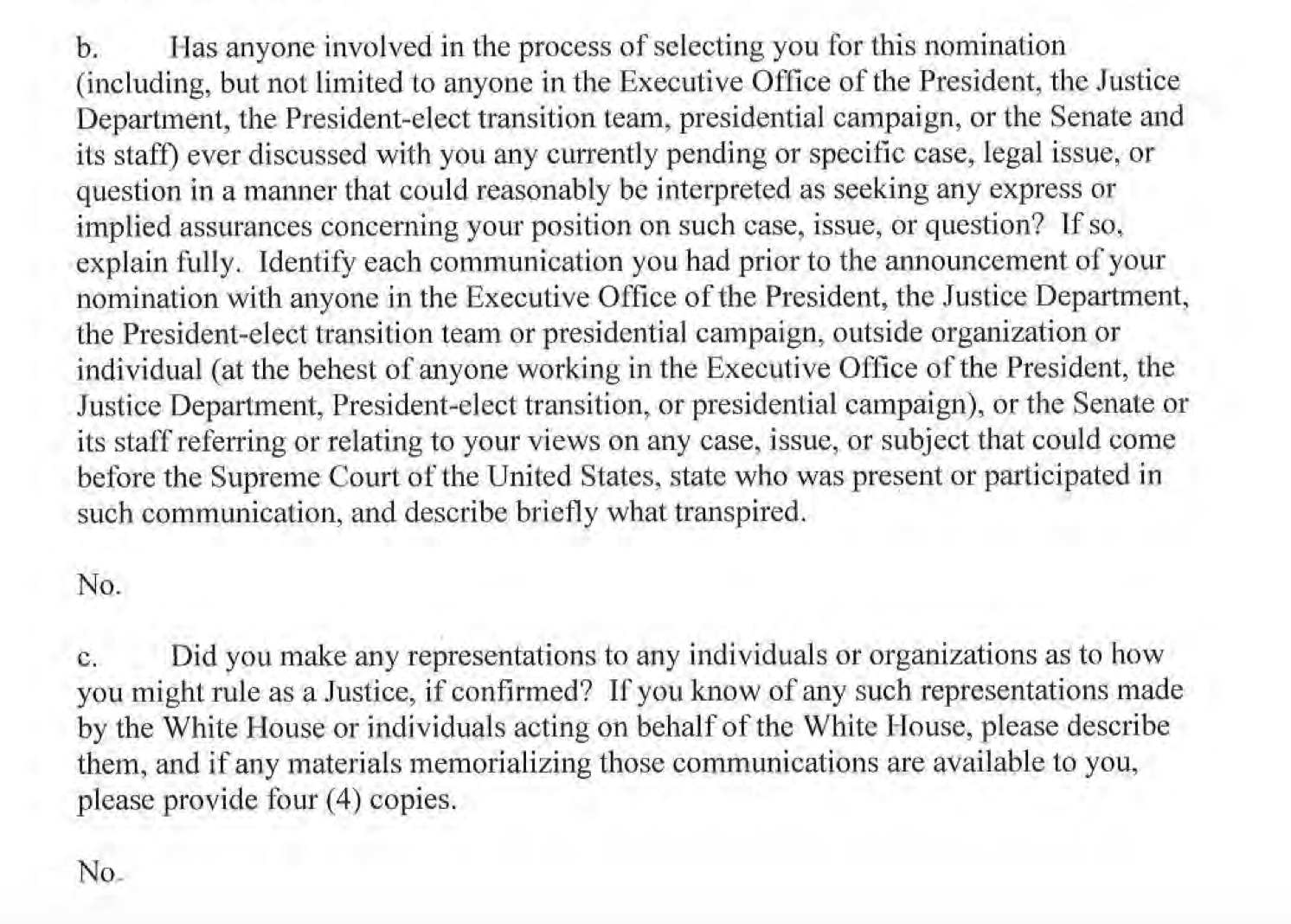

Barrett, for her part, said in the questionnaire that she has not given the White House or any individuals or organizations any implied assurances about how she might rule on a specific legal issue.

[Image via CSPAN screengrab]