The Supreme Court, in another late-night 5-4 decision on Thursday, allowed the execution by lethal injection of a mentally ill federal death row inmate who kidnapped and brutally murdered 16-year-old Jennifer Long in 1998. The Court, in vacating an injunction that was issued by a district court on Wednesday, paved the way for the second federal execution in the last three days. There had not been one in 17 years.

Daniel Lewis Lee was executed on Tuesday not long after the getting overnight go-ahead from the conservative majority on the High Court. The same scenario played out early Thursday in the case of Wesley Purkey, 68.

Purkey’s reported last words:

I deeply regret the pain and suffering I caused to Jennifer’s family. I am deeply sorry. I deeply regret the pain I caused to my daughter, who I love so very much. This sanitized murder really does not serve no purpose whatsoever.

When issuing the injunction on Wednesday, the district court began by describing Purkey’s history of mental illness:

Plaintiff Wesley Ira Purkey is 68 years old. As a child, he experienced repeated sexual abuse and molestation by those charged with caring for him. (ECF No. 1, Compl., ¶ 20.) As a young man, he suffered multiple traumatic brain injuries—first in 1968, when he was 16, and again in 1972 and 1976, when he was 20 and 24 respectively. (ECF No. 1-1, Agharkar Report, at 22.) At 14, he was first examined for possible brain damage, and at 18, he was diagnosed with schizophrenic reaction, schizoaffective disorder, and depression superimposed upon a pre-existing antisocial personality. (Id. at 5.) At 68, he suffers from progressive dementia, schizophrenia, complex-post traumatic stress disorder, and severe mental illness.

Purkey’s lawyers asked for a stay of execution pending an evaluation of their claims that their client was not mentally competent. Both the district court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit agreed that Purkey’s lawyers made a stronger showing that the government. The D.C. Circuit upheld the injunction.

“Given the similarity to Panetti, the deference we owe to the district court’s factual findings, and the procedural posture that requires the Government to make a ‘strong showing’ to obtain a stay, we cannot conclude that the Government – at this stage – has demonstrated the requisite likelihood of success,” the D.C. Circuit ruled.

The 5-4 Supreme Court ruled differently.

Justices Stephen Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor each penned dissents. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg joined Breyer’s dissent; Breyer, Ginsburg and Justice Elena Kagan joined Sotomayor’s dissent.

Breyer argued that the recent executions showed “inherent arbitrariness of the death penalty,” a punishment he sees as flawed and possibly unconstitutional:

I repeat them here in summary form because the Federal Government has resumed executions after a 17-year hiatus. And the very first cases reveal the same basic flaws that have long been present in many state cases. That these problems have emerged so quickly suggests that they are the product not of any particular jurisdiction or the work of any particular court, prosecutor, or defense counsel, but of the punishment itself. A modern system of criminal justice must be reasonably accurate, fair, humane, and timely. Our recent experience with the Federal Government’s resumption of executions adds to the mounting body of evidence that the death penalty cannot be reconciled with those values. I remain convinced of the importance of reconsidering the constitutionality of the death penalty itself.

Sotomayor wrote that the Department of Justice’s “quibbles” over the venue in which Purkey raised his claims were no excuse for the Supreme Court to “shortcut judicial review” of a case involving a death row inmate who “may well be incompetent” for execution:

In any event, the Government’s objection here is not that Purkey failed to raise a valid claim prohibiting his execution. In- stead, the Government quibbles principally with the venue in which Purkey filed that claim. In this posture, that protest does not reflect an “extraordinary circumstanc[e]” that justifies overturning a preliminary injunction. Ruckelshaus, 463 U. S., at 1316. Nor does it support this Court’s decision to shortcut judicial review and permit the execution of an individual who may well be incompetent.

In a statement, DOJ spokesperson Kerri Kupec focused not on the legal claims Purkey raised in recent days but on the “most egregious” crimes he was convicted of committing. Justice was done, Kupec said:

This morning, Wesley Ira Purkey was executed at USP Terre Haute in accordance with the death sentence imposed by a federal district court in 2004. Purkey was pronounced dead at 8:19 a.m. EDT by the Vigo County Coroner.

Purkey violently raped and murdered 16-year-old Jennifer Long, and then dismembered, burned, and dumped the young girl’s body in a septic pond. He also was convicted in state court for using a claw hammer to bludgeon to death 80-year-old Mary Ruth Bales. On November 5, 2003, a jury in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Missouri found Purkey guilty of kidnapping a child resulting in death, and he was sentenced to death on January 23, 2004.

After many years of litigation following the death of his victims, in which he lived and was afforded every due process of law under our Constitution, Purkey has finally faced justice. The death penalty has been upheld by the federal courts, supported on a bipartisan basis by Congress, and approved by Attorneys General under both Democratic and Republican administrations as the appropriate sentence for the most egregious federal crimes. Today that just punishment has been carried out.

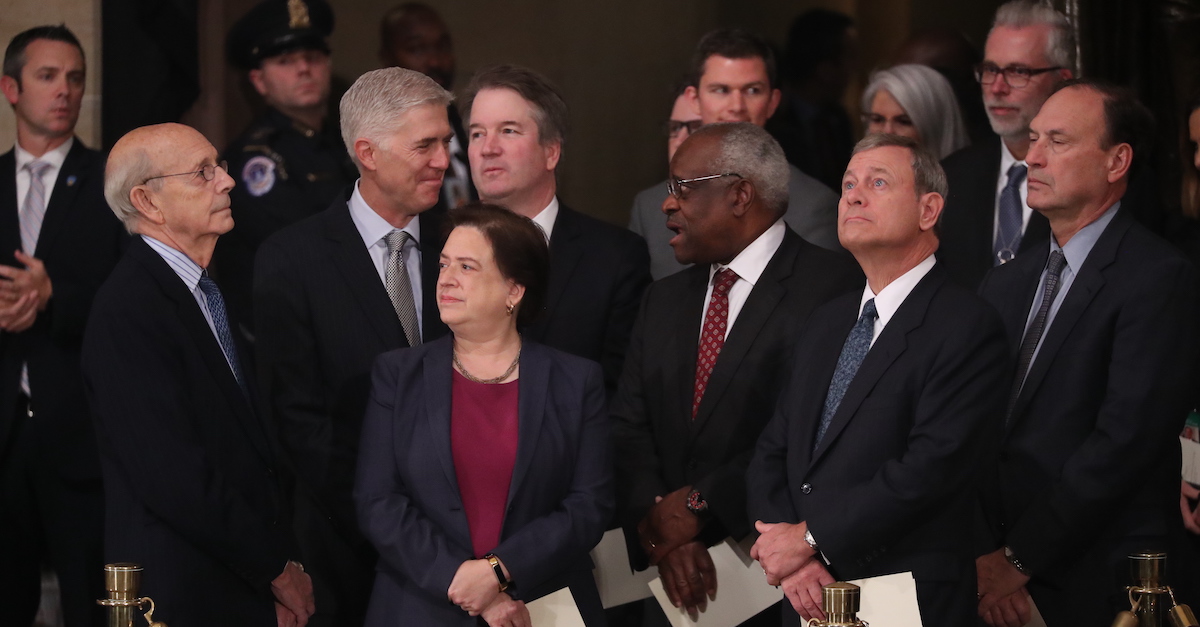

[Image via Jonathan Ernst – Pool/Getty Images]